English immersion summer camp in Hong Kong uses interactive learning to engage underprivileged pupils

- Summer Programme for Immersion in Communicative English, or SPICE, serves more than 200 children aged 10 to 12 every year

- University student interns lead activities such as role-playing, singing and dancing, all conducted in English without any traditional lessons

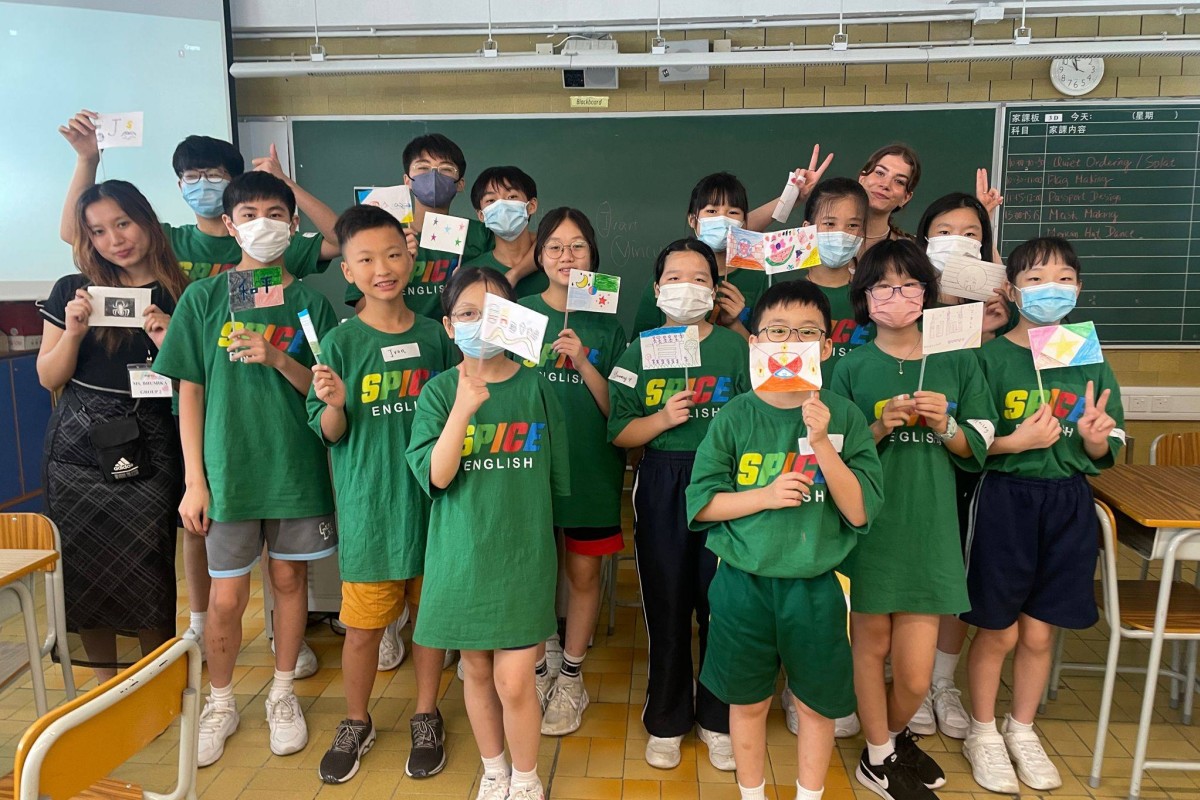

At SPICE camp, students practise their conversational English through fun activities. Photo: Sian Oakley

At SPICE camp, students practise their conversational English through fun activities. Photo: Sian Oakley

Maggie Tsang Ka-yi recalled the heartbreak of saying goodbye to her students on the last day of an English immersion summer programme for underprivileged pupils in Hong Kong.

“When I was saying bye to the students, they even said to me ‘see you tomorrow’, but there was no tomorrow,” shared the 25-year-old programme supervisor. “It was sad, but it was great to see that they really enjoyed the camp.”

Summer Programme for Immersion in Communicative English, or SPICE, is a non-profit programme founded in 2015 by Josephine Chesterton, in collaboration with the Chinese YMCA of Hong Kong. It immerses low-income pupils in an interactive English-learning environment.

The seven-day programme runs three times every summer at various host schools, with university students volunteering to teach the children.

Summer holiday stress: why some teens feel anxious during their break

Managed by Chesterton and her partner Mayumi Eguchi, SPICE serves more than 200 children aged 10 to 12 every year. Activities include role-playing, singing and dancing, all conducted in English without any traditional lessons.

“We believe that you don’t learn a language well if you never speak it yourself,” Chesterton said.

“I thought it would be really nice to do something for local children who were not in a privileged group,” the founder said, adding that the participants usually came from disadvantaged families.

“I ... could put together groups of young adults to work with these local children, and just create a fun English environment where they’re learning English, but they don’t feel it’s a burden. It’s an actual fun summer experience.”

So she recruited university interns from English departments in local schools and the UK – especially those who aspired to be teachers in the future.

Since 2015, they have already worked with more than 20 schools.

“Once a school experiences it, they don’t want to give up their place!” Chesterton shared.

Isis Shum, principal of Ju Ching Chu Secondary School in Kwai Chung, noted how SPICE made a difference for her students.

“The aim of this programme is to help those underprivileged students to learn English in a fun way, so as to help them to build up their confidence. And I think this mindset is exactly what I want to help our students,” she said, from her observation of the camps.

Tramplus courses, competition help Hong Kong students develop the future

Shum noticed the importance of interactive learning, as compared to traditional classroom teaching in Hong Kong: “The SPICE programme actually lets the student explore how to apply and use [English] in the outside world.”

And the educator can vouch for how much her students love the programme.

“At the ... beginning, they will be a little bit shy,” she shared.

“But after the games and the warm-up exercises, and the caring of the group leader, then the students start to join ... and enjoy the game and eventually they will approach me to tell me which game is their favourite of the day.”

With one teacher for every five children, SPICE tries to make sure all the pupils get a chance to practise English.

For the aspiring teachers, they get a real taste of the theories they learn in university.

Samson Ko Shing-kit, a 22-year-old student at Baptist University, got a closer look at his dream profession while volunteering with SPICE.

“I’m very new to teaching and besides the knowledge I have, I have to adjust my attitude and the way to deliver everything to the children so that they can understand me and enjoy their learning environment,” he said.

Apart from local volunteers, SPICE also brings in students from the UK to encourage cross-cultural exchange among teachers.

Survey of Hong Kong student reading habits urges schools to provide more diverse books

Emily Newbon is a student at the University of Worcester, and she said working with students and teachers from a different educational system and country was eye-opening.

“Training to be a primary school teacher, it’s really great to have experience with a range of children ... from Hong Kong,” said the 22-year-old.

Tsang, who was a volunteer for SPICE before becoming a programme supervisor, stressed the importance of interactive learning.

“Some of our students actually come to our camp ... thinking that it’s just going to be another English classroom in which [they] would just sit there and listen to the teachers,” she shared.

“When it’s closer to the end of each camp, I can feel that they are getting more and more comfortable using English to interact with their peers, and also with the teachers,” said Tsang, who will be teaching in a school when the next academic year starts.

Harbour School’s seaweed farms in Hong Kong making waves for environmental impact

In the future, Chesterton hopes to expand the programme to include more volunteers and students.

“Education is what can change the world ... And I feel that the kind of kids we’re dealing with don’t often get the greatest opportunities,” she said.

“So this is just a tiny chance for us to light a spark of interest among the children and make them feel ... [like they] really want to learn English.”