Advertisement

Advertisement

Yu Yongding

Yu Yongding, a former president of the China Society of World Economics and director of the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, served on the Monetary Policy Committee of the People’s Bank of China from 2004 to 2006.

PBOC’s moves are not enough, given the lacklustre economic performance. Beijing should announce large-scale stimulus as soon as possible.

Overtightening hurt China’s economy in the past. Faced with new overcapacities, China should adopt a more expansionary fiscal and monetary policy.

China’s actual household consumption is much higher when properly adjusted for social transfers, purchasing power and housing expenditure.

While it would help if Chinese households saved less and spent more, the economy is probably in a much better position than the pessimists claim

Advertisement

China can expect a consumption slowdown and negligible contribution of net exports to GDP this year. To drive economic growth, investment growth must increase significantly, with quasi-deflation making it possible for the government to boost fiscal stimulus.

China remains well-positioned to achieve much higher growth than most developed economies. The key is to move away from its conservative approach over the past decade, towards expansion.

Beijing will have to be very targeted in expanding fiscal and monetary policy to boost investment. But the ultimate aim must be to buy space for structural reforms.

The yuan has weakened significantly against the dollar multiple times since 2015, with the People’s Bank of China fighting to defend its value for fear of a collapse. But despite a sharp depreciation again this year, policymakers have held back, suggesting a stronger confidence in the Chinese economy.

China’s old playbook of using off-budget infrastructure spending to boost growth is saddling local governments with unmanageable levels of debt. Instead of focusing on keeping its own balance sheets clean, the central government could save money and minimise risks by assuming this debt itself.

The US government has not had problems servicing its debt in the past as investment income has been positive for decades. Amid rising global tensions and aggressive monetary tightening, though, it would be a mistake to take America’s external sustainability for granted.

If all foreign assets – public and private – can be frozen in a split second by reserve-currency countries, policymakers should not even waste their time with hedging measures like diversification.

Though necessary to combat soaring prices, China’s reining in of the real estate sector has slowed investment growth and weakened the economy. As Beijing seeks to stabilise growth, there is ample room to ease policy without letting developers fall back into their old ways.

The problems in the energy and property sectors, though serious, do not pose a systemic risk to the economy, despite the alarming news headlines. The more urgent task for Beijing is to reinvigorate growth that has slowed since 2010.

With the pandemic persisting, Beijing has been alert in applying policy remedies where needed, but its economic performance will inevitably be largely determined by the success of its fight to control the coronavirus.

The divergence in the increases in consumer and producer prices is the result of Chinese producers’ preparations for a post-pandemic surge in demand, which has yet to materialise. This lack of price pass-through has kept consumer inflation low, but squeezed the profits of downstream producers, which will ultimately undermine economic growth.

China’s growth in 2020 was driven by fixed-asset investment and exports. This is not ideal. To achieve higher growth in 2021, China needs a larger increase in infrastructure investment, and the government may have to issue more bonds than planned.

Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals depends on cash-strapped governments finding an untapped source of financial resources. This must provide the impetus for countries to create a robust and coordinated regime to crack down on financial crimes and tax evasion.

Dual circulation does not imply any fundamental change in the growth paradigm, and China will not turn its back on the world no matter what happens.

Many Chinese economists oppose monetary and fiscal stimulus, citing factors like population ageing. But their arguments are far weaker than the case for expansion: whatever the economy’s potential, China is performing below it.

The prospect of slower Chinese growth is gaining widespread acceptance, but this trend is dangerous. For the sake of China and a global economy primed for recession, Beijing must arrest the decline in GDP growth and implement a powerful stimulus package.

The Chinese central bank’s decision to let the yuan fall below 7 per US dollar had little to do with trade or currency wars. Rather, it represented an important step towards reforming China’s inflexible exchange-rate regime.

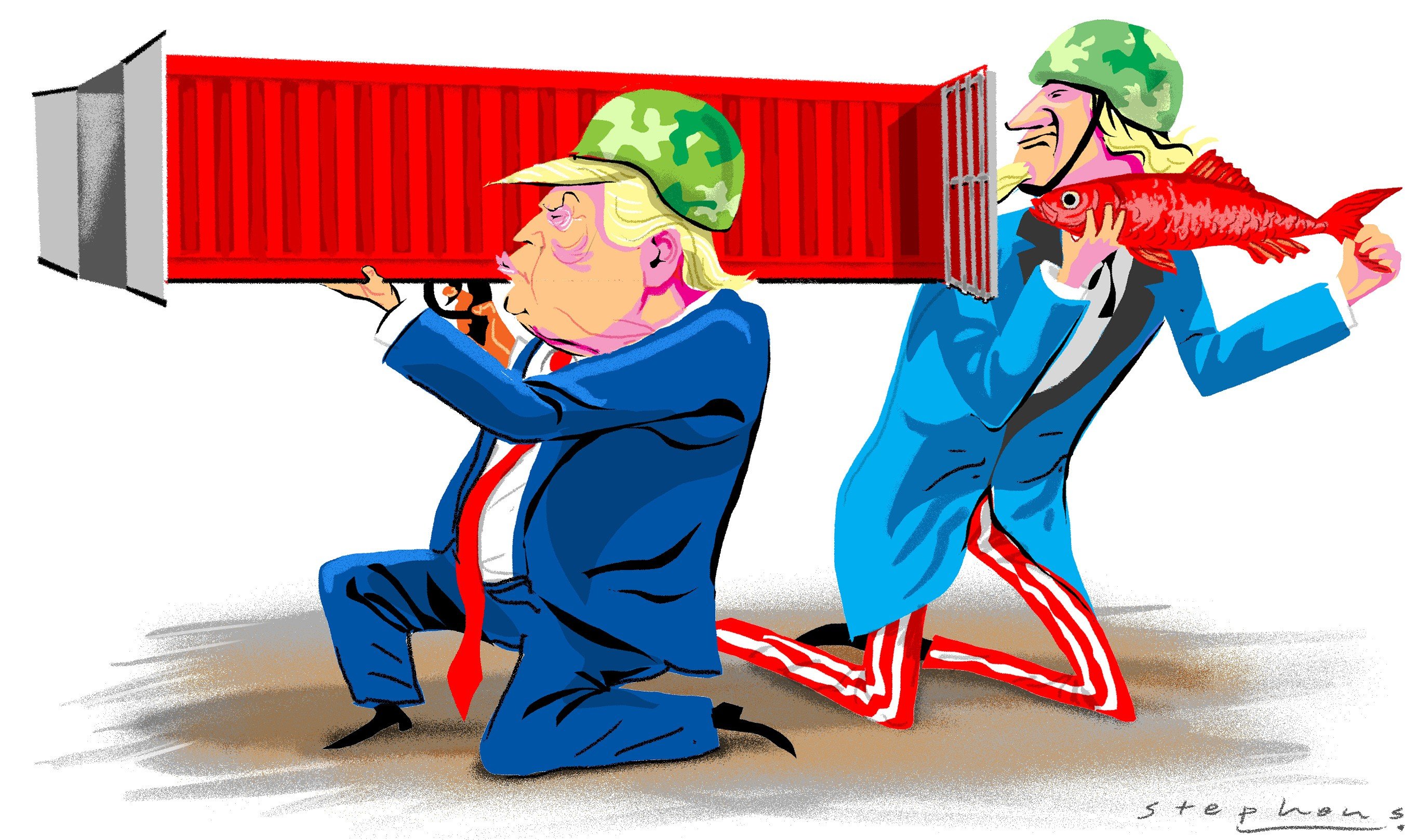

The Trump administration wants US companies to leave China and it is up to Beijing to persuade them to stay. It must also prepare for the possibility of a currency war, and US sanctions on Chinese financial institutions.

When setting growth targets, a too-conservative estimate could have huge consequences for China’s economy and its people. Beijing should seek as much expansion as possible – focusing on infrastructure investment – while making the necessary structural changes.

The Chinese central bank can’t devise an effective monetary policy when it is juggling too many tasks, including keeping the yuan stable. Beijing can’t obsess about currency stability when it needs to prevent a financial crisis.

Yu Yongding says previous US governments saw the benefits of preserving the status quo on trade with China. The trade war should prompt China to recognise that buying US Treasuries instead of making domestic investments is not in its own interests.

While the current depreciation in the yuan appears sharper than in the 2015-17 crisis that rattled investors, the PBOC has yet to intervene in the market the way it did then, signalling that it is serious about exchange rate reform.

America’s Section 301 investigation, based on rumour and half-truths, ignores the benefits that US companies have gained from their voluntary entry into China, China’s anaemic investment into technology in the US, and Beijing’s improvement in IP protection.

Optimistic growth forecasts for the Chinese economy overlook the degree to which slowing fixed-asset investment – though good for the long-term health of the economy – will affect near-term prospects.