Advertisement

Advertisement

Raffaello Pantucci

Raffaello Pantucci is a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London and a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore. His work focuses on terrorism, counter-terrorism and China's Eurasian relations. He has a forthcoming book on China's relations with Central Asia and most of his work can be found at raffaellopantucci.com. Prior to Covid-19, he spent a good portion of his time traversing the Eurasian continent seeking understanding about the new continental dynamics.

China’s infrastructure initiative has attracted criticism and inspired a cacophony of competing plans, including the G20’s economic corridor but fundamental needs are getting lost in the rush to conjure up new visions.

The grouping seems too inherently illogical to be a threat, with core members in conflict and countries with vastly different economic, strategic and military weight. But the point is about normalising a world order of institutions not led by the West.

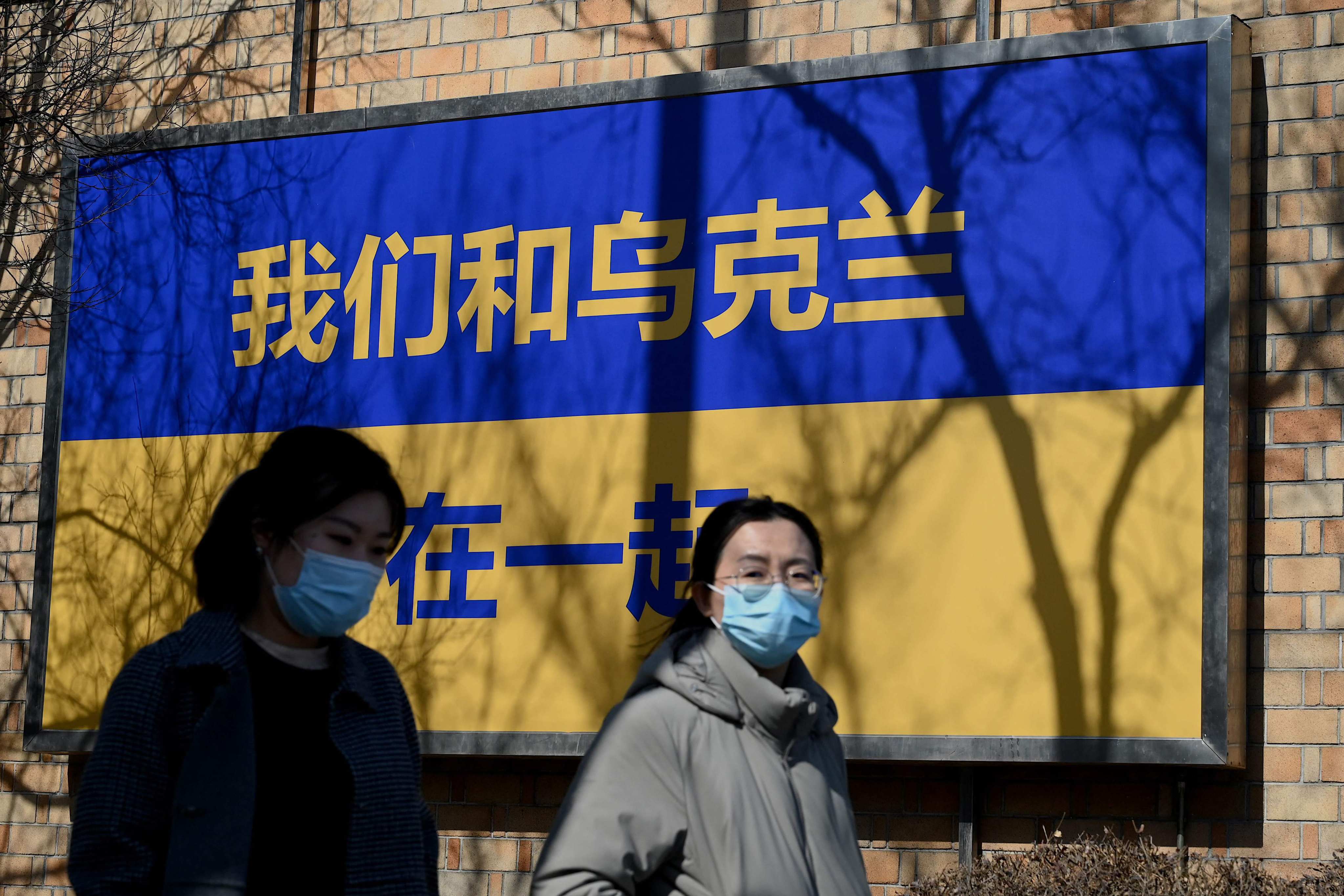

The Chinese embassy’s protest against the treatment of a Chinese influencer at the Russian border is not a sign of a crack in relations. Neither is China’s participation at the Saudi-sponsored peace summit on Ukraine.

Recent moves by China and Russia to bring diplomacy to bear on the Taliban government are unlikely to work.

Advertisement

It remains to be seen how much China will enforce the agreement given its dislike of confrontation, but that matters less than others engaging with Beijing. The world order is shifting and the West needs to find a better way to answer the offer Beijing is putting on the table than simply dismissing it.

Sanctioned and isolated, Tehran has less to offer Beijing than Moscow, which can at least boast a powerful military and global presence. Within Iran there is also wariness of Chinese investment, and not even shared concerns about Afghanistan have helped to spur cooperation.

In the decade since the Belt and Road Initiative was first discussed, China has become a major player in Eurasia, yet it appears unwilling to step in to help resolve the conflicts in its own backyard.

Central Asia’s increasingly tense relations with Russia have made closer ties with China attractive, but achieving that is not without its problems. Far from Beijing proving a hedge against Moscow, the opportunities on offer in Russia might simply increase the competition for China’s attention.

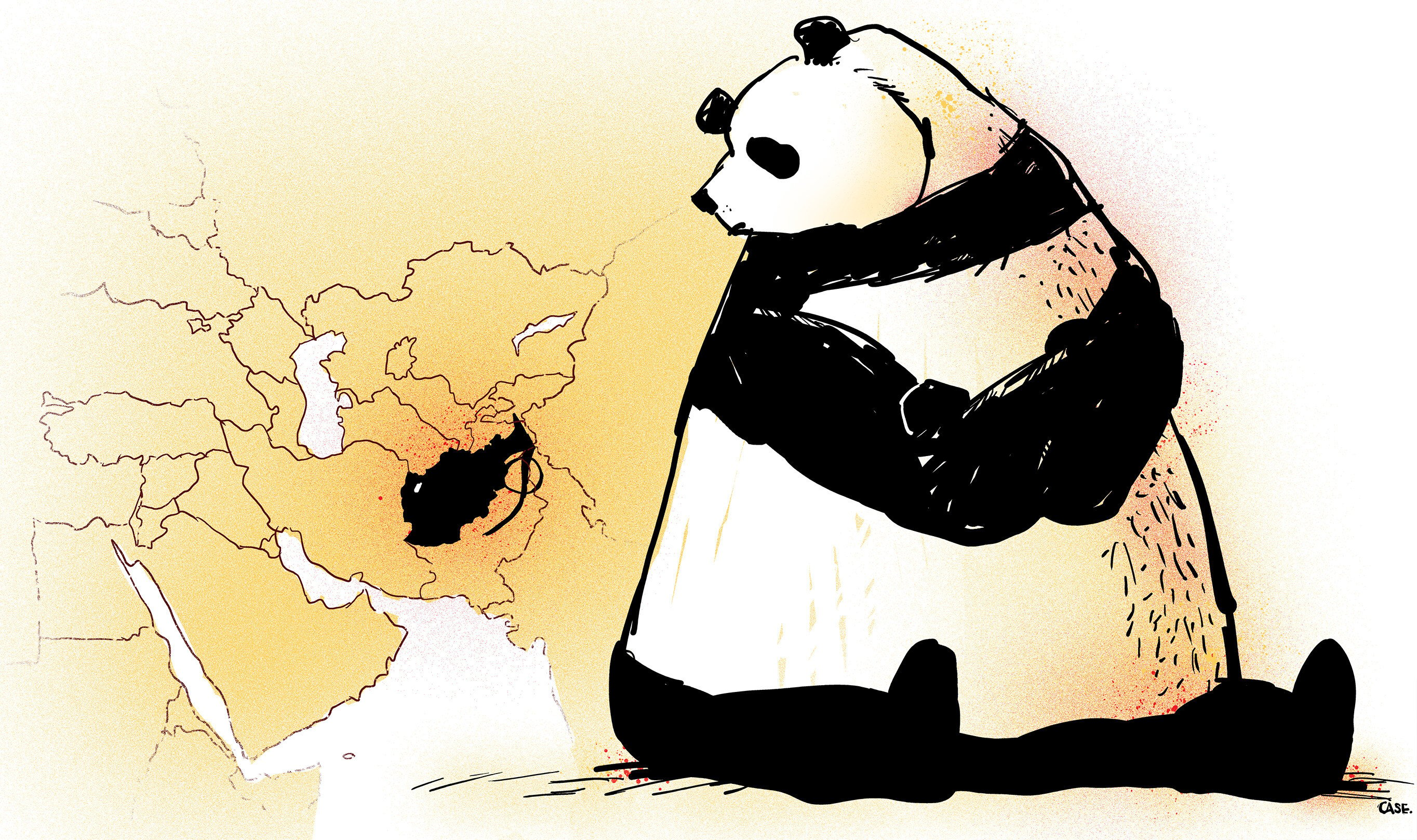

Rather than being quick to gain an edge in Afghanistan following the US withdrawal, China, along with Russia and Iran, remains uneasy about security threats coming from the country. Meanwhile, the Taliban government is frustrated at the lack of economic support being provided by its neighbours.

Shehbaz Sharif’s rise to power in Pakistan puts China in an advantageous position as its western neighbours are all friendly to Beijing. This also means China has a stake in the many problems that emanate from this region, though, and will be forced to take a more active role.

The US and EU’s condemnation of Russia and repeated calls for their allies to do the same reflects a world view in which democracies stand united against autocracies. In reality, drawing battle lines is far more difficult when interests and values rarely align.

From Afghanistan to Kazakhstan and now Ukraine, the Eurasian heartland has fallen prey to three forces: authoritarian incompetence, Russian adventurism and Chinese passivity. Beijing may be happy to sit out the chaos for now but it will ultimately spill over and create problems it cannot ignore.

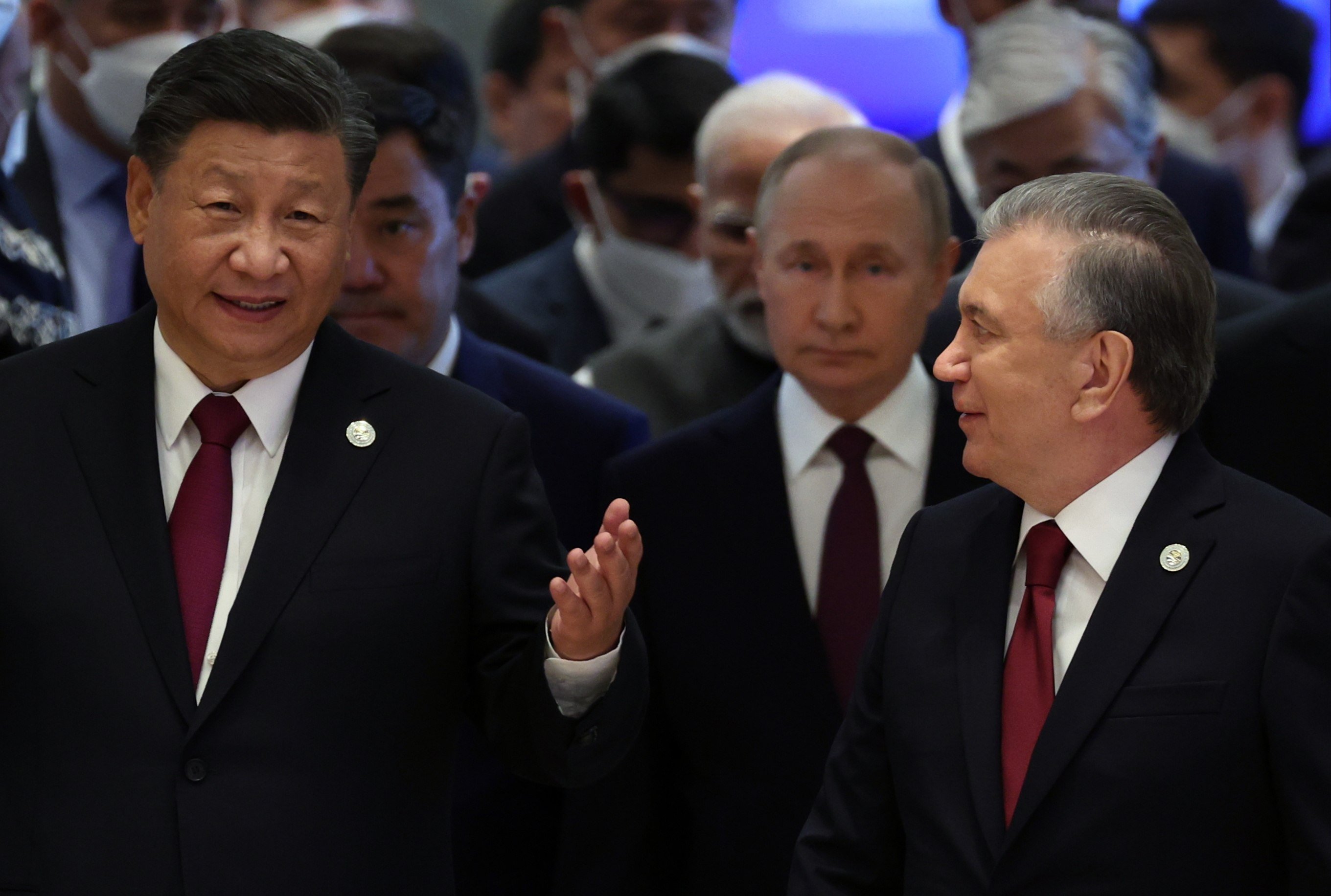

Suggestions of China-Russia rivalry for power in Central Asia miss the mark. In reality, while both are active in the region, their roles are more complementary than competitive.

The flak Beijing has drawn for its Taliban engagement is not just unfair but also misses the point. If China’s Afghan strategy is to be faulted, it’s for doing too little.

There appears to be little evidence supporting Taliban assurances that trouble will not spill over onto Chinese soil. China needs to take a more proactive role in supporting the government in Kabul and visibly deploy more resources.

Competing with China dollar for dollar is pointless as Chinese banks and state-owned firms are driven by different concerns. Building up governance capacity in developing countries will help them push back when Chinese firms step over the line.

The balance in Afghanistan seems weighted more towards opportunity than challenge for China. Beijing might believe it knows how to avoid pitfalls, but history is littered with powers that thought they could control the Eurasian region.

What Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to the region may lack in material achievements, it makes up for in good optics. China is a major player in the region. In highlighting this, Wang has undermined Western-driven condemnation and achieved China’s foreign policy goals.

Chinese officials have praised the initiative and its goal of improving cross-border flows of people and goods. The reality has been different, though, with China’s neighbours and partners frustrated by border closures and lengthy delays.

The belt and road was not meant to be a single large infrastructure project. Rather, it provides the great machine of China’s external-facing apparatus with a new driving vision.

Beijing’s reluctance to get involved in the Eurasian unrest is in line with its attitude towards conflicts that do not impinge on its own security. But, given China’s growing influence, its disinterested posture muddies the waters for others trying to resolve unrest.

China has never taken India seriously, while New Delhi has continually hedged and never made a clear choice about what it wants from its relationship with Beijing. The possibility of miscalculation is growing and a dangerous new normal is setting in.

Chinese people, embassies and projects are increasingly the target of separatist and terrorist violence as protests against Uygur treatment grow. As a big player, China’s mere presence and support for the authorities in the region makes it a target for local anger.

Is there a new axis between China, Russia and Iran against the West? Not quite. Beneath the surface of the anti-US alliance, there are undercurrents of hostility and scepticism. Across Eurasia, there is also a reluctance to take sides.

In the face of growing global criticism, Beijing may be painting itself into a corner with its narratives, which fuel an increasingly angry nativism in China, forcing it to take the dangerous path of doubling down on confrontations.

Forget Pax Sinica, China’s medical outreach is failing. Even though Russia and Iran, its closest allies, may be on the same page, underlying tensions remain. There is a global leadership gap but Beijing is not filling it.

Beijing is toning down its rhetoric for the grand plan and rethinking its massive international infrastructure programme, Raffaello Pantucci writes.

While regional players like Iran seek to bring China into the conversation, Beijing continues to rely on the rhetoric of non-interference. Its single-minded focus on its own interests will see China become stronger.

Raffaello Pantucci writes that growing regional anger must be kept from spiralling out of control and creating broader havoc.

Raffaello Pantucci says it is not clear that Beijing fully appreciates the role it is taking on by trying to broker peace in strife-torn Afghanistan and getting a Taliban-inclusive political structure in place.