Advertisement

Advertisement

Kerry Craig

Kerry Craig, executive director, is a global market strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management, based in Melbourne. Prior to joining JP Morgan, he worked in the UK pensions industry and also held several economic research positions in the New Zealand government. Kerry holds a master’s degree in economics from the University of Auckland and is a CFA charterholder.

The view that the US economy will achieve a soft landing is increasingly becoming consensus, driven in part by encouraging GDP growth figures. However, reports on credit card debt, oil prices and continued political dysfunction in Congress could turn a soft landing into a slippery slope to recession.

While it’s not possible to rule out another US rate rise this year, the Fed looks to be entering a holding pattern. A resilient US economy together with the gradual labour market adjustment means inflation is falling slowly, which will keep rates higher for longer.

Markets are cheering economies’ resilience in the face of rising interest rates. In particular, US inflation drawing unexpectedly closer to the 2 per cent target suggests an end to rate rises after July.

In the current bull market run, the heavy lifting is being done by a handful of tech companies, amid enthusiasm for generative AI. However, this enthusiasm could be challenged in the short term, given the sharp rise in valuations, even as AI is likely to remain a long-term influence.

Advertisement

The all-powerful American consumer will be tested in an uncertain economy – but the capital expenditure of companies may end up being the determining factor.

Higher interest rates, tighter credit conditions and a steadily depleting stock of household savings all add to the case for a US recession and potentially a period of weak global growth. So shouldn’t this mean an appreciation in the US dollar? It depends.

Economists have raised their expectations for first-quarter growth and recent data points squarely towards the resilience of the global economy. However, the outlook for growth is complicated given that central banks must now balance controlling inflation, the prospect of slowing growth and financial stability risks.

The ripples from Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse have flipped market expectations of Fed policy, from further rate rises to cuts by the end of the year. As inflation falls and the US economy slows, the Fed faces a trade-off between growth and inflation, with the added complication of ensuring financial market security.

China lifting its pandemic-induced restrictions and the associated economic impulse are driving up investor sentiment and the global economic outlook. While the expected rise in domestic consumption will provide an economic boost, there are longer-term structural issues that still need addressing.

The many moving parts of the inflation outlook, including housing and wages, make it difficult to determine the exact path for policy interest rates. The easing of price rises in recent months reduces the risk central banks will overcommit to fighting inflation, but that is not the same as cutting rates.

Rising interest rates, a strong US dollar, an energy crisis and the pandemic combined to create stiff headwinds for Asian economies this year. However, if the US dollar stops rising, the Federal Reserve pauses interest rate increases and China reopens, Asia could be poised for a better 2023.

Investors are looking for the US stock market trough and starting to wonder if it has already passed, but multiple bear market rallies are not uncommon. The sooner uncertainty over market risk clears up and a full recession is either priced in or not, the sooner equity markets can start to recover.

While other sectors appear to be cooling off, the US labour market is showing resilience amid rising wages and a shrinking pool of workers. Any slowing in the pace or magnitude of the Fed’s rate increases will be closely linked to the performance of the labour market.

US stocks have made back much of their losses from the first half of the year, and there are signs the rally in equity markets still has some way to go.

Much has changed since 2013, when emerging markets were badly hit by US monetary tightening. Today, central banks in developing nations have been quick to confront inflation and post-pandemic demand, and with smaller deficits than a decade ago, there is less chance of panic selling of currencies.

While the shift from quantitative easing to tightening has happened very quietly, the path for running down the balance sheet was well telegraphed by the US central bank. This is in sharp contrast to the rhetoric from several Fed officials on interest rates.

Falling consumer confidence and stock sell-offs have sparked concern about a growth slowdown in the US, which given its economic size could drag down the rest of the world too. However, a US downturn is not inevitable, especially given the healthy labour market.

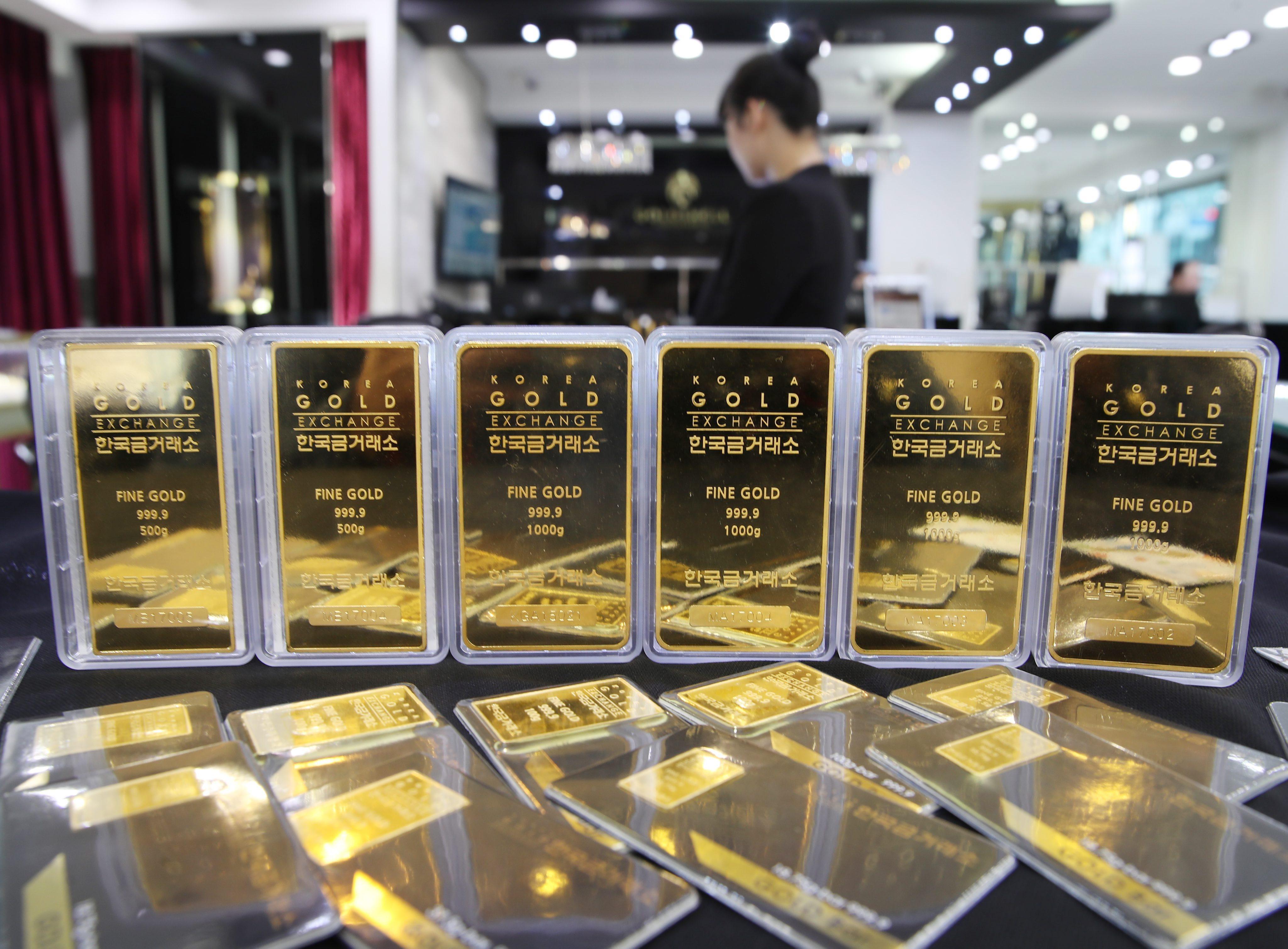

Hawkish central banks and the possibility of extended lockdowns in Chinese cities have adversely affected sentiment. The rise in Treasury yield, the yen’s depreciation and the erosion of gold’s value by inflation means investors need to consider their options carefully.

Unlike bonds in the US and other advanced economies battling sky-high inflation, emerging market bonds can offer positive real income. Still, high food and energy prices mean investors must be selective; exporters of commodities are better-positioned than manufacturing countries reliant on goods from elsewhere.

Investors are worried the policy support freely offered by central banks in the past two years will be withdrawn quickly and aggressively. Market volatility is expected to persist until there is greater clarity about the pandemic, snarled supply chains and interest rates.

This year may well see not only the end of bond purchases by the Fed and the start of the rate hike cycle, but also the first steps in reducing its swollen balance sheet. The highly valued parts of the market, such as growth stocks and tech stocks, will come under pressure.

Amid a warming US economy and growing inflation, Fed hawks will push for rate rises to start as soon as mid-2022 at the next key meeting. But how much the Fed allows tapering to quicken will depend on Omicron risks

Despite warnings about rising inflation amid supply-chain disruptions and tight labour markets, the gold price has remained steady. Gold is likely to lose its appeal as inflation pressures ease and central banks shift away from emergency policy settings.

The key is the speed at which monetary and fiscal policy is tightened and how fast wage growth rises. Supply and demand imbalances will resolve but pressures from the labour market shortage and continued fiscal spending will linger.

The potential for a slowdown in the world’s two largest economies is feeding concerns about a peaking in global growth. Both countries are also facing another wave of Covid-19 cases. The Delta variant is the biggest risk when it comes to the outlook for any economy.

Part of the reason could be worries about what lies ahead, in particular the spread of the Covid-19 Delta variant. The dampeners on government bond yields will fade over time, and the prospects for brighter economic growth should send yields higher.

Falling yields might be a sign that messages around the transitory nature of inflation are starting to sink in. The onus is on the US Federal Reserve to justify its accommodative stance and lean into its guidance that it will tolerate higher inflation before raising rates.

Funding stimulus measures through higher corporate and personal taxes may hit US equities. While technology, communication services and health care sectors may be adversely affected, industrial, energy and materials sectors stand to gain.

Investors expecting the currency to fade have been flummoxed by a reinvigorated US economy. Renewed dollar depreciation will come, though, as the sugar rush of stimulus fades and other countries’ vaccine programmes catch up.

Investors will be weighing how credible the Fed’s outlook is for a US economy supercharged by a massive stimulus boost that may cause inflation to spike, forcing an early move on either bond purchases or the rate outlook.