Advertisement

Advertisement

Dani Rodrik

Dani Rodrik, a professor of international political economy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, is the author of Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy.

Middle powers from India to Nigeria can lead on many pressing issues and offer a multipolar vision that doesn’t depend on superpowers.

Focusing on the small number of real beggar-thy-neighbour policies could lead to better economic outcomes and also make for better politics.

It may be impossible to simultaneously combat all three issues under current policy trajectories. It’s time for new policies that put these trade-offs behind us.

To defeat the far-right, the left must return to its roots and restore good jobs, dignity and economic security to workers.

Advertisement

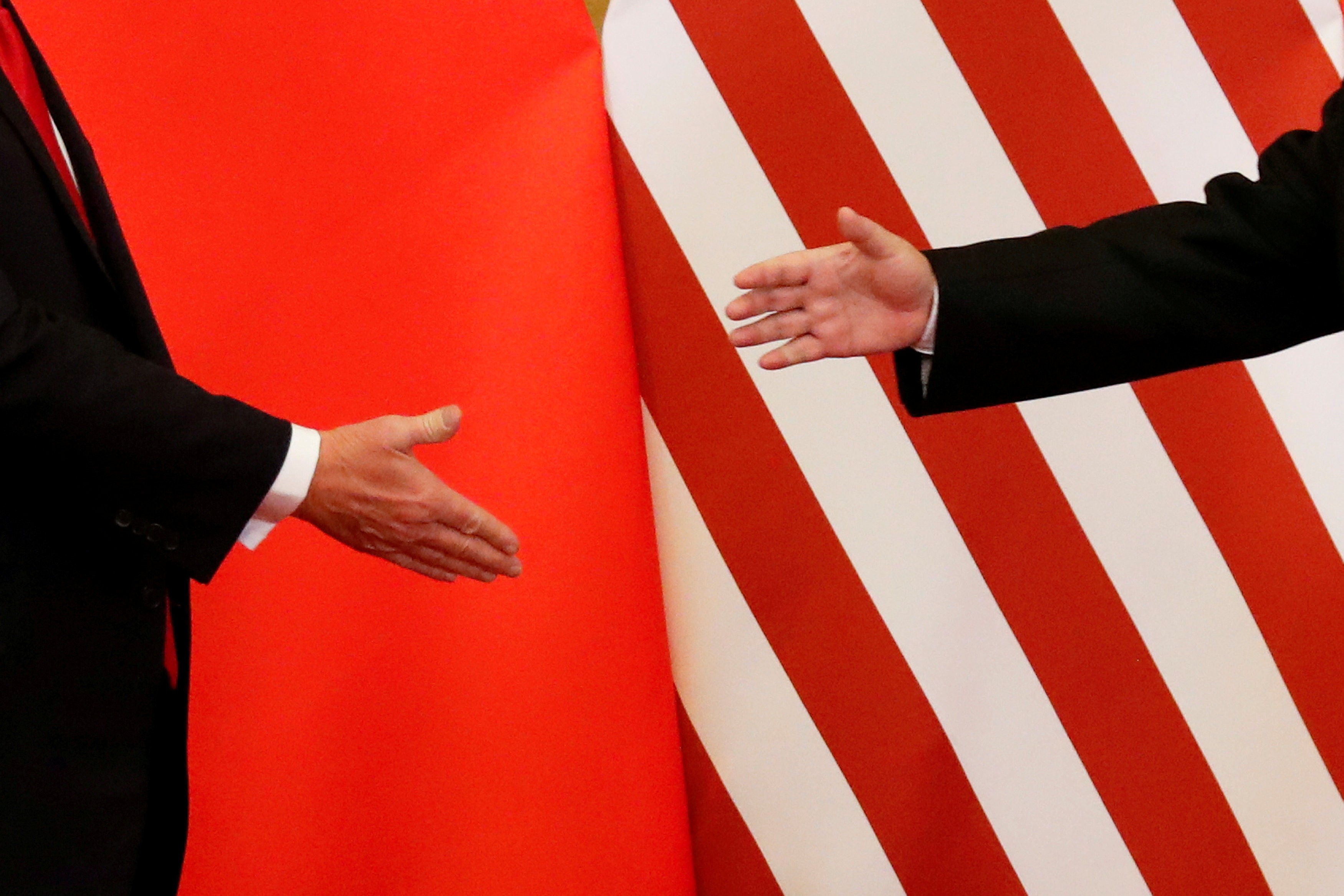

What some decry as protectionism and mercantilism ruining the global economy is really a rebalancing towards addressing important national issues. The biggest risk is not this broader reorientation – which should be welcomed – but US-China rivalry that threatens to hurt everyone.

Scientific and technological innovation might be necessary for the productivity growth that enriches societies, but it is not sufficient. Without the right kind of complementary policies, technological progress might not lead to sustainably rising living standards and could even set a country back.

In recent remarks, the US Treasury secretary and national security adviser have described US export controls targeting Chinese tech sector as narrow in scope. Washington seems to understand that overly broad restrictions in the name of national security will hurt the global economy and provoke Beijing.

Western protectionist policies are often driven by legitimate domestic and global concerns, such as climate change. Instead of condemning them, developing nations must seek their own prospect-boosting policies that benefit the global economy too.

With hyper-globalisation in decline, the world has an opportunity to right the wrongs of neoliberalism and build an international order based on a vision of shared prosperity. To do so, we must prevent the national security establishments of the world’s major powers from hijacking the narrative.

With many countries urgently needing debt relief to ward off economic collapse, the elements of grand deals need updating to new global realities. International financial institutions must shift focus from an overemphasis on macroeconomic targets to socially acceptable policies that support green growth.

Government programmes that promote sustainable production at home have been criticised for pricing out global competitors. But given the urgency of the climate crisis and lack of global cooperation, national initiatives may be the best way forward, regardless of their impact on trade.

While great powers will protect their national interests, it should not be for the express purpose of punishing the other side or weakening it in the long run. By choosing confrontation, they have handed the keys to the global economy to their national security establishments, jeopardising peace and prosperity.

If the free market is dying, what replaces it won’t be found among other 20th-century models, but in new ideas that address contemporary challenges. Increased state support can help drive innovation and create jobs, but protectionist attempts to revive old industries are misguided.

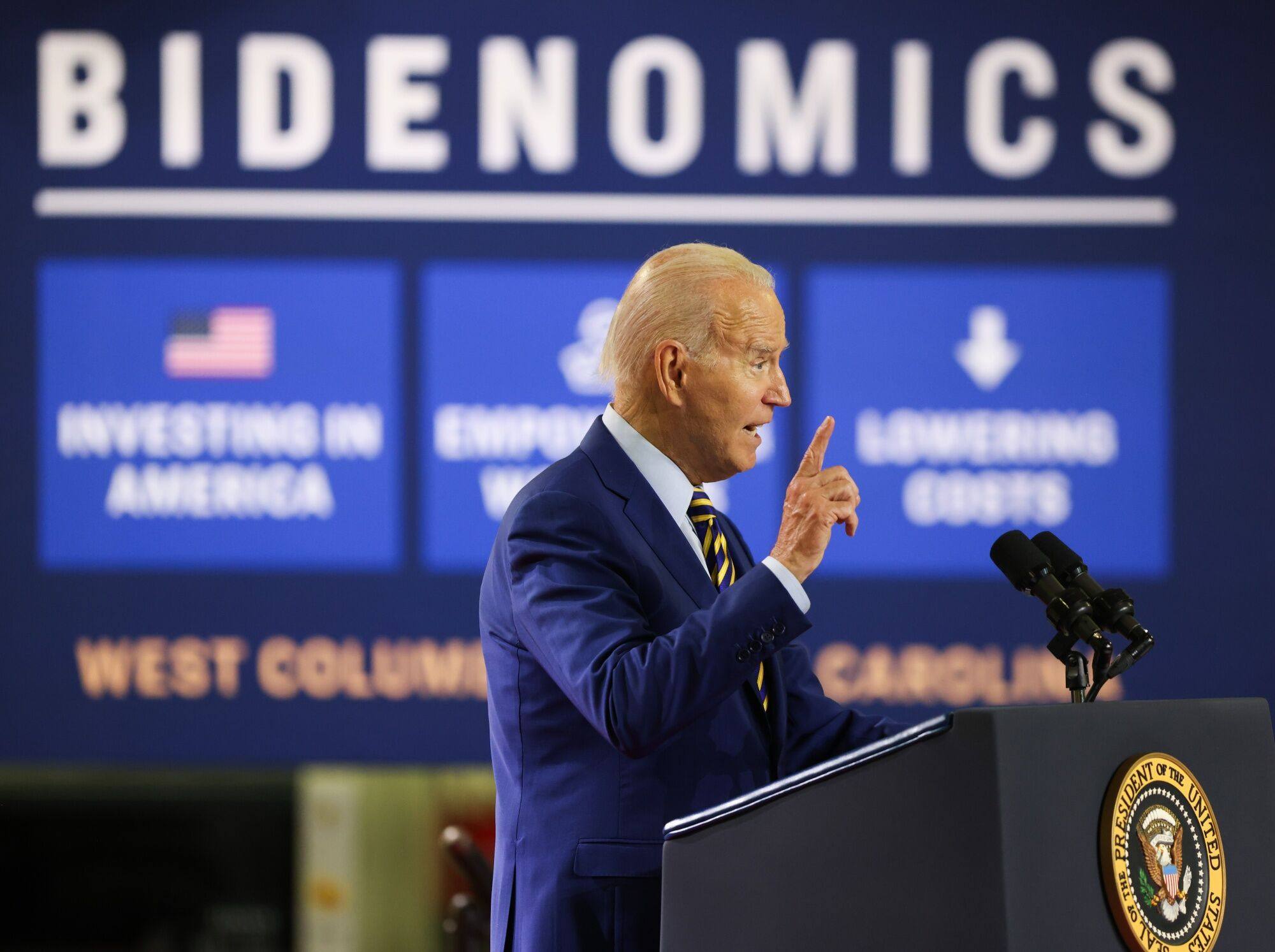

There are signs of a reorientation towards a new economic policy framework as global sentiment turns away from globalisation. Productivism, which emphasises production and investment over finance and aiding local communities over globalisation, is garnering bipartisan support.

US foreign policy goals are often self-serving, and its designs for a rules-based international order primarily reflect the interests of its business and policy elites. What is good for America may not be good for the world, and the sooner it recognises that, the better.

With China’s rise as a geopolitical rival to the US, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, strategic competition has reasserted itself over economics. However, a scenario is possible with a better balance between the prerogatives of the nation state and the requirements of an open economy.

A new ‘realist’ order centred around security rather than economic prosperity may be more prone to conflict and less able to collaborate on global issues like climate change. But it doesn’t have to be that way – it is possible to balance national interests and autonomy with international cooperation.

Does a China with a decidedly different economic and political system and strategic interests of its own have to imply an inevitable clash with the West? The structure of great power rivalry might exclude a world of love and harmony, but it does not necessitate a world of immutable conflict.

The deal for a global minimum corporate tax rate struck by the G7 sets a low threshold to assuage developing countries’ concerns while the global apportionment of profits will enable high-tax jurisdictions to recoup some of their lost revenue.

The ideas dominant since the 1980s produced highly financialised, unequal and unstable economies. The Biden administration has launched an overdue economic transformation. The point is not to create the next ossified orthodoxy, but to learn to adapt policies.

Tax incentives and open-ended investment subsidies to attract firms to lagging regions are not that effective. Instead, Biden should invest in sectoral training programmes, which equip workers with skills tailored to specific industry needs.

Their candidate won a record number of votes, but Democrats face criticism for not doing better and for policies seen as both too liberal and too conservative. Concerns over social issues and losing good jobs to technology and globalisation could haunt them.

Despite a swell of private-sector support for corporate social responsibility, the effectiveness of relying on companies’ enlightened self-interest is unclear. Firms can be a reliable partner for the social good only when they speak with the voices of those whose lives they shape.

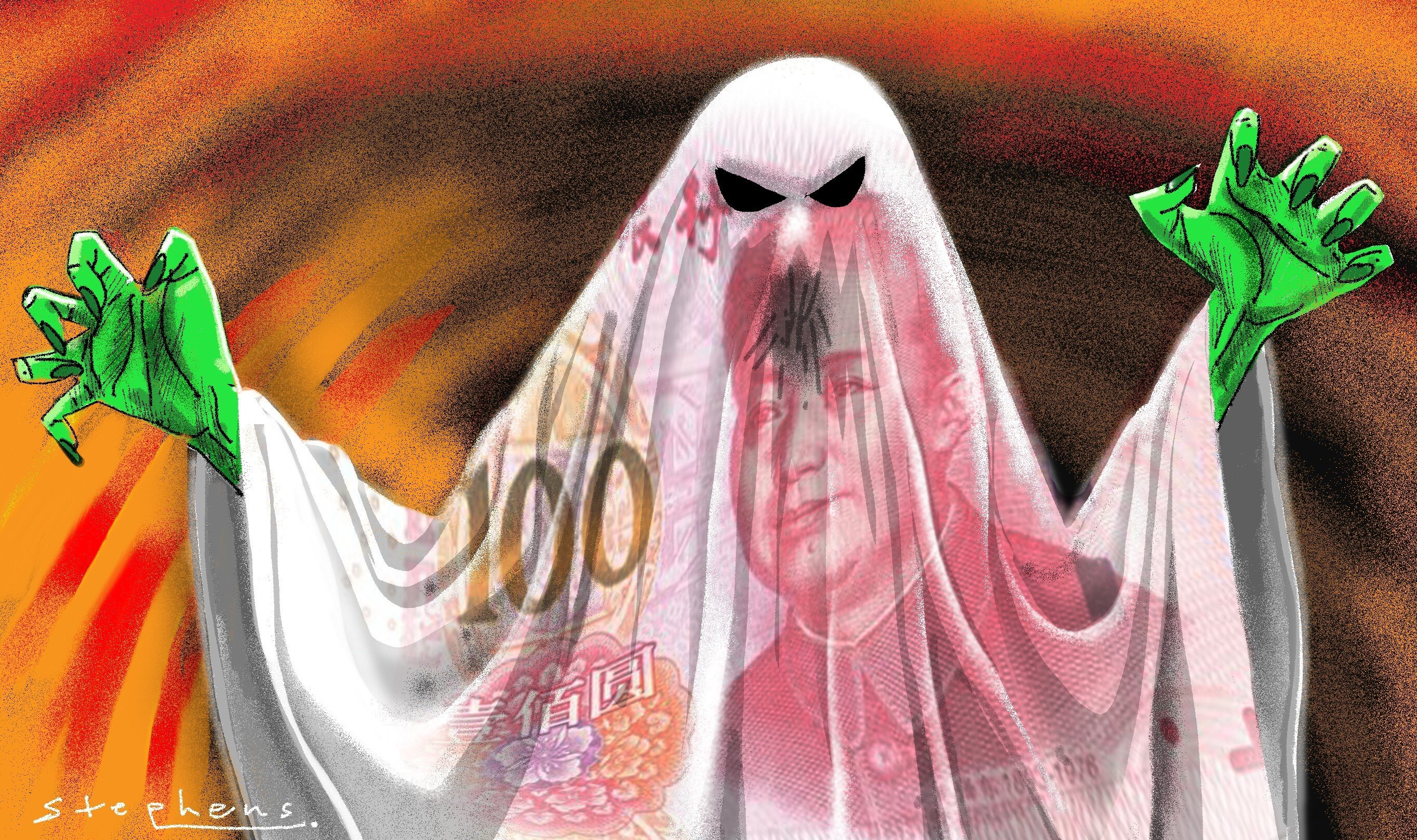

Huawei’s difficulties are a harbinger of a world in which national security, privacy and economics will interact in complicated ways. Countries must agree on a new regulatory patchwork which allows them to pursue their own interests without exporting their problems.

The innovation agenda has been captured by narrow groups of investors and firms whose values and interests don’t necessarily reflect society’s needs. The public sector provides the infrastructure that sustains private R&D and can help ensure innovation mirrors social priorities

We should not allow economics to become hostage to geopolitics or, worse, to reinforce and magnify US-China rivalry. The objective for the West should be to build more productive, more inclusive economies at home – not simply to outcompete China.

The talk everywhere is about decoupling and bringing supply chains home, but the retreat from hyper-globalisation need not mean trade wars. It is possible to envisage a more sensible, less intrusive model of economic globalisation.

Stalked by Covid-19, countries and politicians have in effect become exaggerated versions of themselves. This suggests that the crisis may turn out to be less of a watershed in global politics and economics than many have argued.

Trade policy in the US and advanced economies has been driven by globalisation and corporate interests, and left behind communities. With Warren, the US may be able to reimagine trade policy in the interests of society.

China and the US, like all other countries, should be able to maintain their own economic model. But international trade rules should prohibit national governments from adopting ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies.