Advertisement

Advertisement

Lanxin Xiang

Lanxin Xiang is professor emeritus of the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, and visiting fellow at the Schuman Center of Advanced Studies at the European University Institute (EUI) in Florence. He is founder of PN Associates Strategic Consultancy, and a distinguished fellow at the Stimson Center.

A fan of pro wrestling, Trump’s approach to diplomacy may be unorthodox, but it resembles a common-sense tradition rooted in American philosophy.

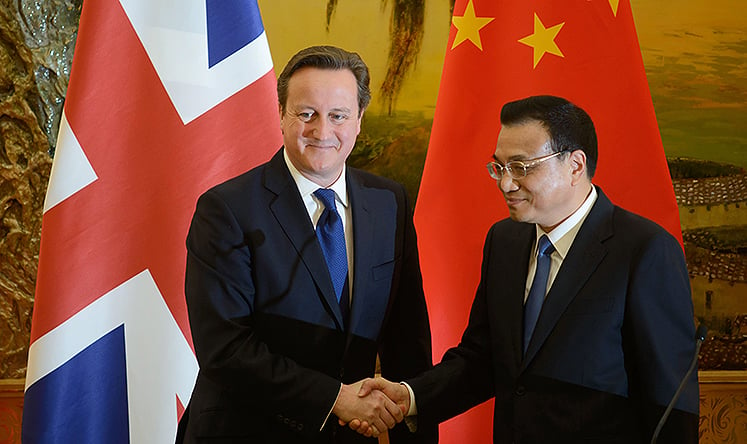

As Sullivan made clear in an extensive speech, the US is making a partial return to a realpolitik approach to China. However, the policy framework remains unchanged: China is still an ideological ‘other’ that is not democratising as the US wished.

While Russia has proved it has the capacity to keep fighting, Ukraine must depend on support from its Western allies that is ultimately unsustainable. When economic sanctions don’t work and military operations go nowhere, a ceasefire must be considered.

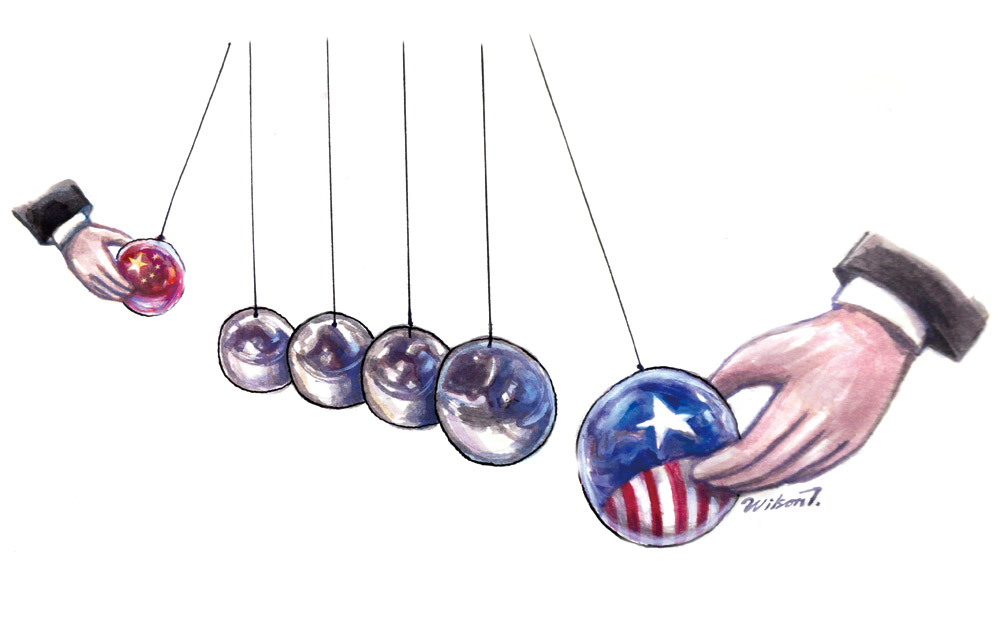

The two most powerful nations have entered a perilous phase of miscommunication and mis-signalling – which usually occurs as a prelude to an unexpected war.

Advertisement

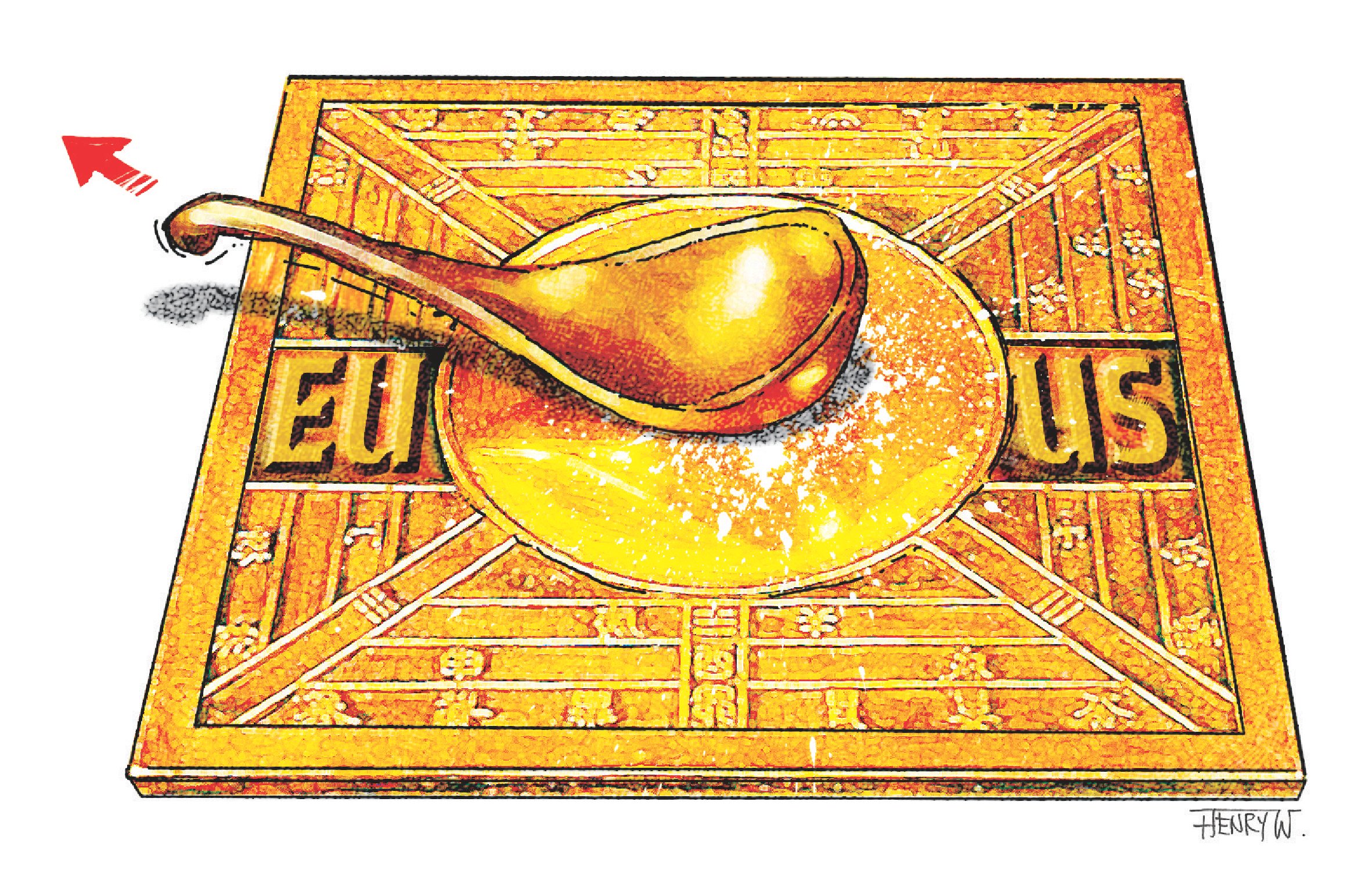

The label, introduced in 2019, pleases no one, having failed to curry US favour or extort Chinese concessions. Instead, the EU should focus on maintaining strategic autonomy.

Washington cannot claim to want to avoid a conflict with China while simultaneously pushing its vision of a US-led global order, especially when such an order insists on excluding and outcompeting China in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

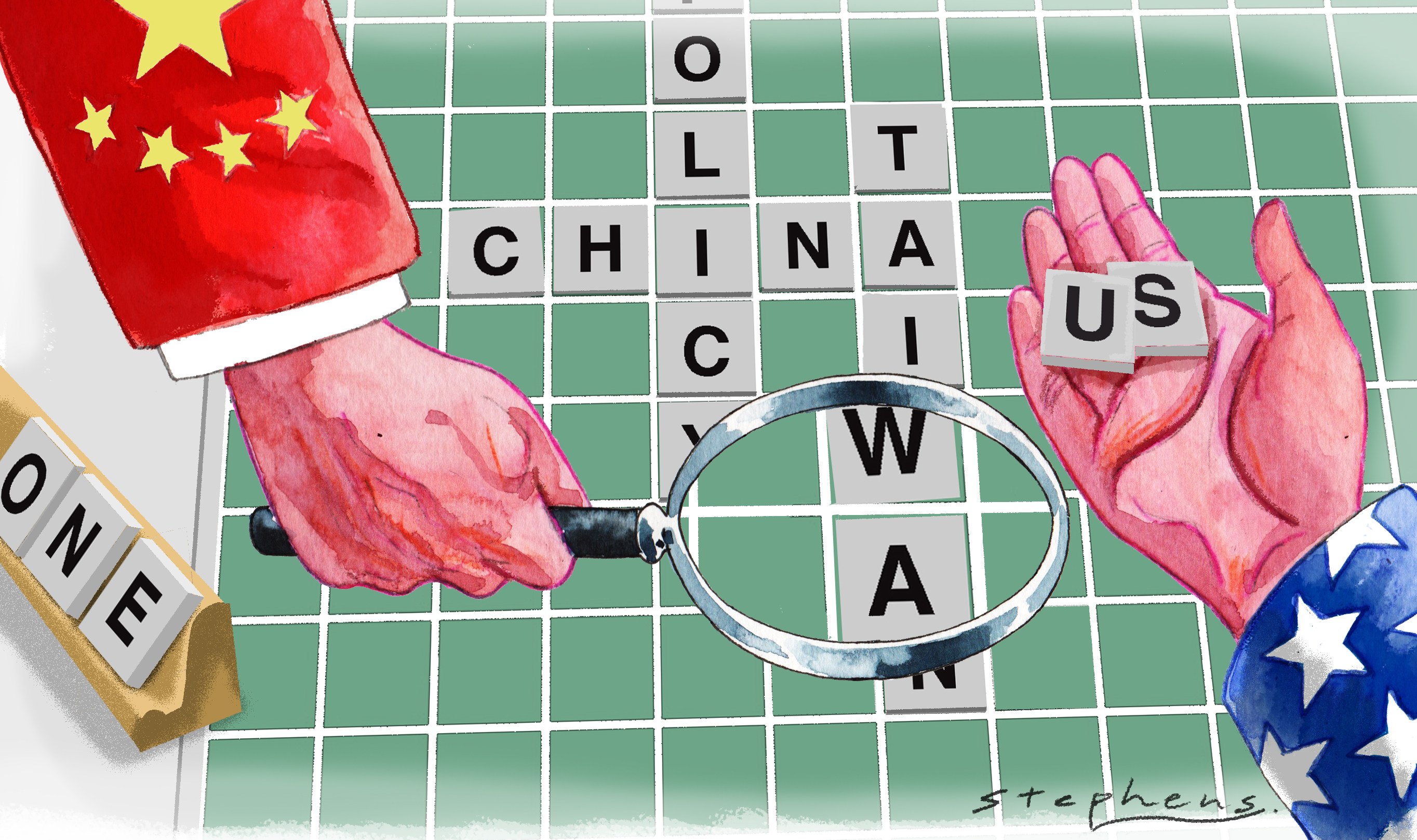

Since the early 1970s, the US and China have skirted by the specifics of ‘one China’, but as relations between the two deteriorate, the lack of real agreement on the issue could become explosive. Increasingly, ‘strategic ambiguity’ only serves as a cover for the US’ ‘one China, one Taiwan’ policy.

The war in Ukraine reflects a breakdown of the Western management of ecumenical peace in Europe since the end of the Cold War. Now the West is focusing its attention on China and treating Taiwan as the Ukraine of the East, raising the prospect of another damaging war.

Unless the West goes back to the racial tribalism of the last century, a unified Western strategy against China is not morally and practically sustainable. China should continue to control its hubris as there is no reason to panic, either from a democratic alliance or an ‘Asian Nato’ meant to strangle China.

Both Washington and Beijing lack a long-term strategic vision. US President Donald Trump is desperate to be re-elected, while China’s assertive ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy and overconfidence could lead to miscalculation and disaster.

Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws has for more than 200 years led many in the West into believing that the tension in the Chinese political system is created by the lack of "democratic legitimacy" and the suppression of individual freedoms.

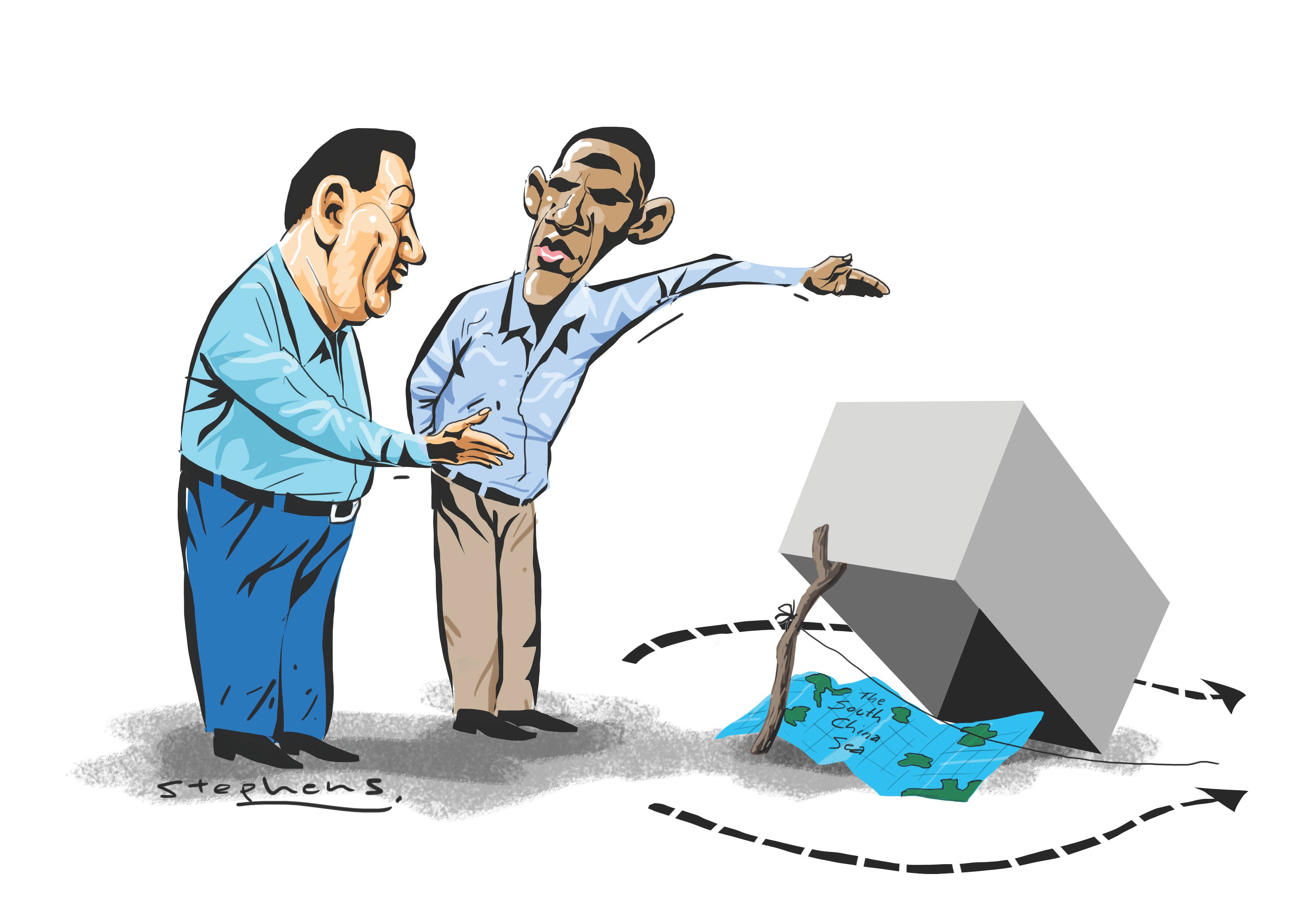

The Chinese saying, "playing music to an ox", describes the phenomenon of two people talking past each other. It's apt imagery for the recently held Sino-US Strategic and Economic Dialogue.

China has just published its first national security blue book. Although official media labelled it "the most authoritative" report on national security since the establishment of the super-secretive National Security Committee, it presents such a panicky psychology that one has to wonder who wrote it.

Not so long ago, China's policy elite were still debating whether the nation's relationship with the US would remain "the most important among all important bilateral ties".

It seems ironic that China, the former lead opponent of the Soviet Brezhnev Doctrine, should have supported the Russian position in Ukraine. The former Soviet Union utilised the doctrine to launch military action in other socialist "brother" countries, such as Czechoslovakia in 1968, and the West did nothing.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's sensational statement at Davos claiming that the current relationship between Japan and China was akin to Anglo-German alienation in 1914, on the eve of the first world war, provoked an angry response from China. Foreign Minister Wang Yi said such a statement was "incomprehensible" and a "confusion of time and space".

Xi Jinping presided over a key conference recently on China's relations with neighbouring countries, or its "periphery policy" (zhoubian zhengce). The level of attendance, including all Politburo members working in Beijing, was the highest in recent memory.

Of late in the Chinese media, party ideologues and officials have launched seemingly brave campaigns to reject the existence of any "universal values". It stems from President Xi Jinping's speech at a national conference for propaganda chiefs in August, in which he stressed the need to step up ideological work to maintain Chinese characteristics in development and domestic governance. Xi never mentioned "universal values", but many commentators seem to be interpreting his speech to benefit their own interests.

Singapore's prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, made a speech to a Japanese audience earlier this year, in which he claimed that if the Chinese government should decide to use non-peaceful means to take the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, it may lose the world. The statement apparently irked the Chinese a great deal, albeit belatedly. The nationalistic paper Global Times made a big fuss of it some two weeks ago. But Lee's argument is not entirely wrong.

Edward Snowden seems to have opened a Pandora's box.

The Chinese leadership may have good reason to regret taking bad advice from its ideological team. The idea of declaring a new political slogan, the "China Dream", at the outset of the new regime has backfired so badly that one wonders if the catchphrase can outlast Hu Jintao's "harmonious society", which survived for more than two years.