Advertisement

Advertisement

Donald Kirk

Donald Kirk is an author and journalist from Washington, D.C., and travels to South Korea, with stops in London, India, Pakistan, the Middle East, Japan, Hong Kong and the Philippines, among other places, writing on the confrontation of forces in the post-September 11 era. He was the Seoul correspondent for the International Herald Tribune from 1997 to 2003. Before gravitating to Northeast Asia, he covered much of the Vietnam War for the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Star. He has also written books on Korea, notably Korea Betrayed: Kim Dae Jung and Sunshine and Korean Dynasty: Hyundai and Chung Ju Yung.

Empty statements of concern and denials of responsibility typify the US response to Israel’s slaughter of Palestinians in Gaza and the mass killings in Jeju in 1948, both of which were made possible by US weapons and official ambivalence over Washington’s role in allowing the attacks to happen.

While the spectre of nuclear war hangs over the region, other flashpoints may explode first, drawing in not just South Korea but also Japan, China and even Russia. North Korean denuclearisation remains a fantasy but another round of negotiations would at least be better than war.

China’s launch of its domestically designed and built aircraft carrier signals its emergence as a major naval power in the struggle for dominance in the Pacific. While there are obvious implications for the US and possibly Taiwan, South Korea should also be stirred into expanding its own naval capability.

Nato’s overriding consideration is that nobody wants to shed blood for Ukraine, and Putin knows it. The Russian president is gaining a victory of sorts by making it highly unlikely that Ukraine will join Nato. Could he call Biden’s bluff and order a full-scale attack?

Advertisement

The US is considering a ‘no first use’ policy, when states are seeking to modernise their nuclear arsenals. Rather than demanding that North Korea alone get rid of its nukes, global denuclearisation should be on the agenda.

Demands for a treaty are part of a bill in the US Congress that ignores North Korean human rights violations and its nuclear missile programme. Those pushing for a treaty assume all sides must agree to end the Korean war, which North Korea shows no interest in doing.

The resounding success of the Tories in Britain has its echoes in Seoul, where hundreds of thousands rebel against Moon. The two situations have differences, but in both the middle and working classes have grown weary of out-of-touch leftists.

For all its tests, North Korea can’t risk firing missiles for real. However, the US has made the world a more dangerous place by killing a missile treaty with Russia and intending to deploy more missiles in Asia.

A court case triggered the latest row between the East Asian democracies, but decades of animosity have contributed. The two sides should remember all that unites them, however, and that an escalating dispute means neither wins.

If Moon can create a special new agency to investigate corruption, we can expect him to use it against his political opponents, who have been emboldened by his failing diplomatic and domestic policies.

The South Korean leader’s strategy for bringing North Korea to negotiations has included silence on Kim Jong-un’s ruthlessness and rights abuses, which could jeopardise South Koreans’ hard-won rights.

With opposition mounting at home and sanctions still blocking inter-Korean cooperation, the relative calm on the peninsula may be small consolation for Moon Jae-in.

Aside from a meeting with Donald Trump, Kim Jong-un’s trip to Hanoi may open his eyes to the possibility of unleashing the entrepreneurial spirit in a tightly controlled society, at no risk to his grip on power.

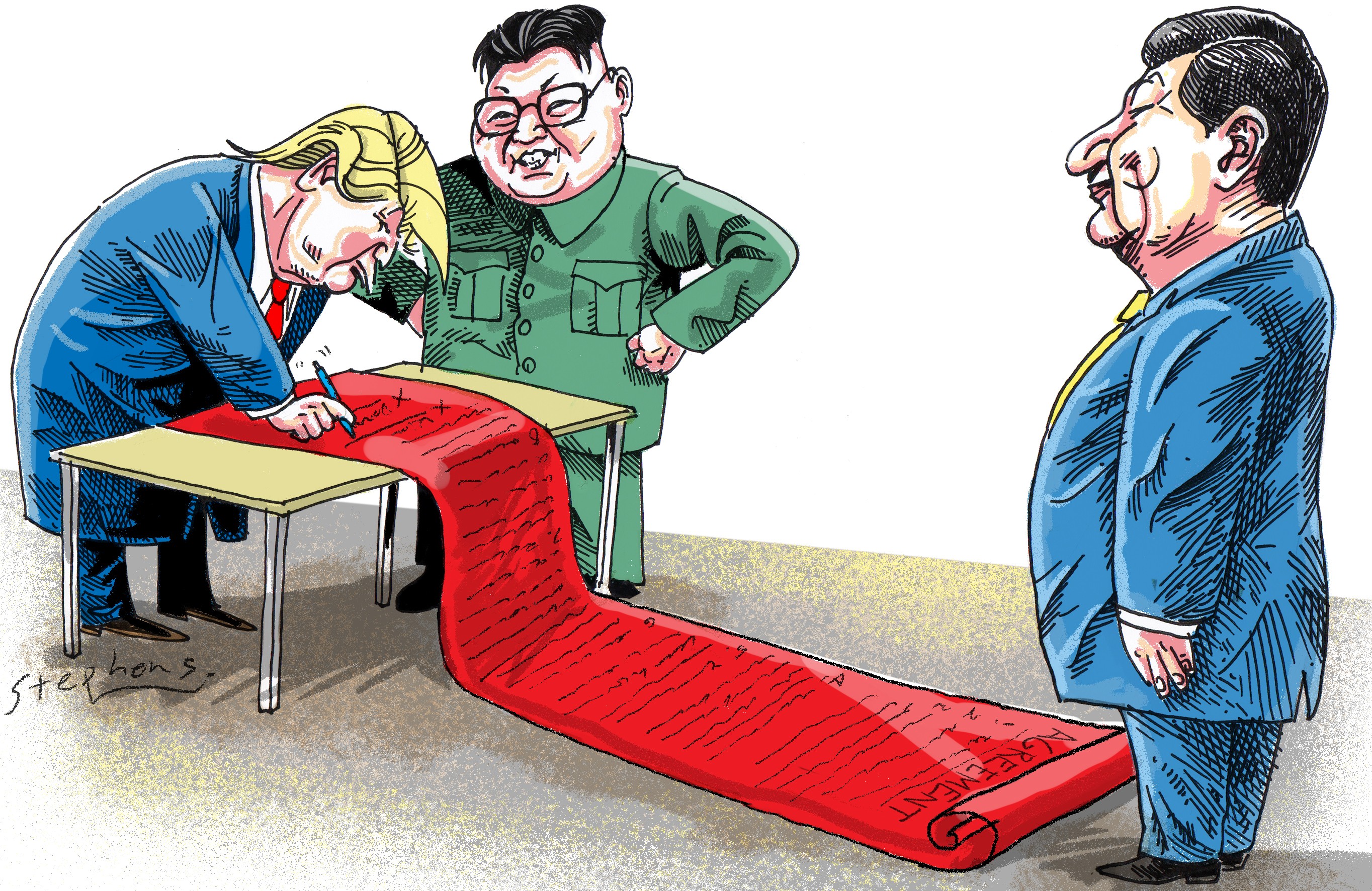

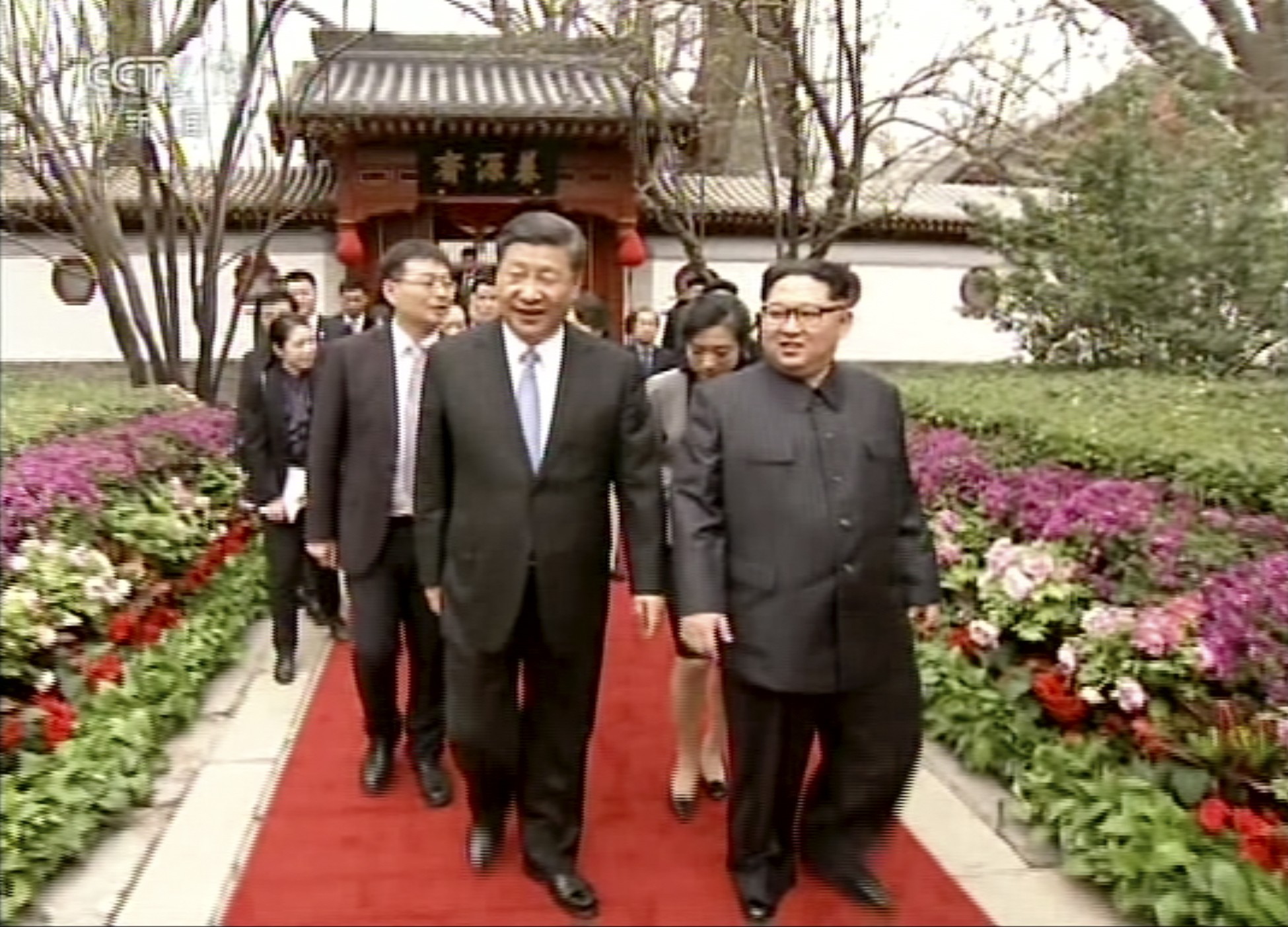

Despite hopes that China will encourage Kim Jong-un to seek a detente, what Beijing really wants is to make life difficult for Washington as the trade war and Huawei case drag on.

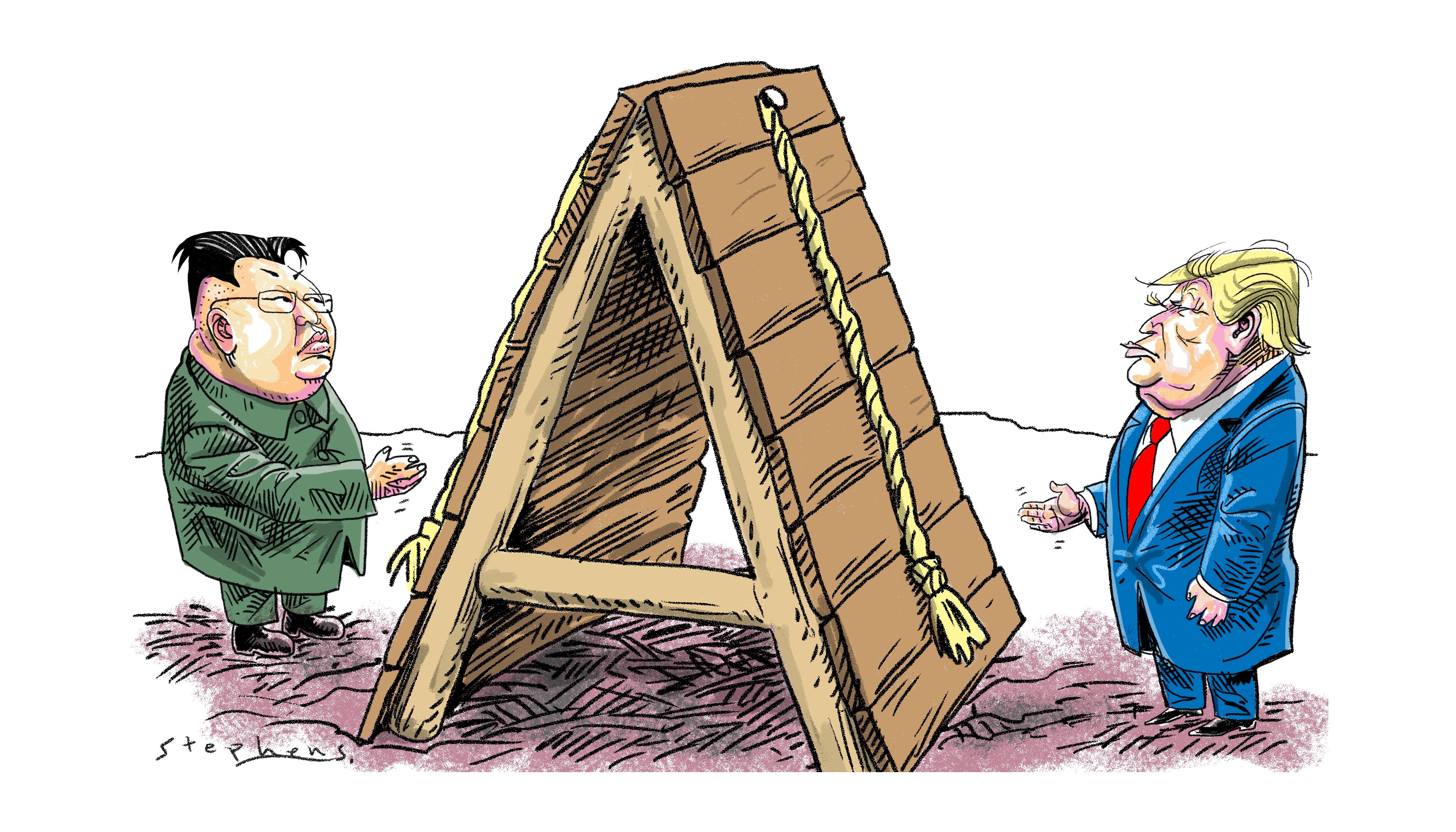

North Korea and the US may not agree on what ‘denuclearise’ means, but is there harm in meeting again? The answer is yes, actually, if these summits give the impression that diplomacy has been tried and did not work.

North Korea has used US soldiers’ remains as a moneymaking scheme in the past, and now may be after a bigger payoff – a peace declaration and exit of US troops from the Korean peninsula

US trade deficits make Trump’s aggressive strategy understandable, but China’s reliance on the US market has played a major role in keeping disputes – particularly over territorial waters – under control. As Trump hinders access, that could change

Donald Trump has raised false of hopes of Korean reunification but Kim Jong-un’s agenda cannot coincide with democracy.

The US president may have earned his ‘dotard’ nickname in Singapore by signalling interest in reducing America’s military presence in East Asia, leaving China free to pursue its dreams of regional – and continental – dominance.

The first hurdle in preparing the US-North Korea summit is the US’ unwillingness to meet Kim Jong-un on his home turf in Pyongyang, but a compromise there only means moving on to thornier issues, like North Korea’s definition of ‘denuclearise’ and American unwillingness to withdraw from South Korea.

A looming trade war with the US, Japan’s shift to the right under Abe, and the continuing challenges to China’s geopolitical position in the region are all part of the calculations that convinced Xi a meeting was necessary.

By capitulating to most of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s demands before the Olympics, South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in has sent the message that he is all too willing to compromise.

Reflecting on the history of the Olympics in Korea, the differences are apparent between the 2018 Winter Games and the 1988 Summer Olympics – today, the demonstrations are against North Korea, and the North can do much more than blow up airliners

The US president faces several difficult tasks as he meets leaders in Tokyo, Seoul and Beijing, not least of which will be keeping the pressure on North Korea while easing China’s concerns about THAAD.

Donald Trump’s over-the-top declaration can’t hide the fact that military action against the North would be deeply unpopular at home, costly and opposed by North Korea’s neighbours