Fukushima’s water release: what we know and why Hong Kong and South Korea have raised concerns

- Japan will begin releasing water from the power plant 12 years after one of the world’s worst nuclear disasters, when an earthquake and tsunami killed around 18,000 people

- Move is backed by UN atomic agency but condemned by Greenpeace; individuals have raised safety concerns

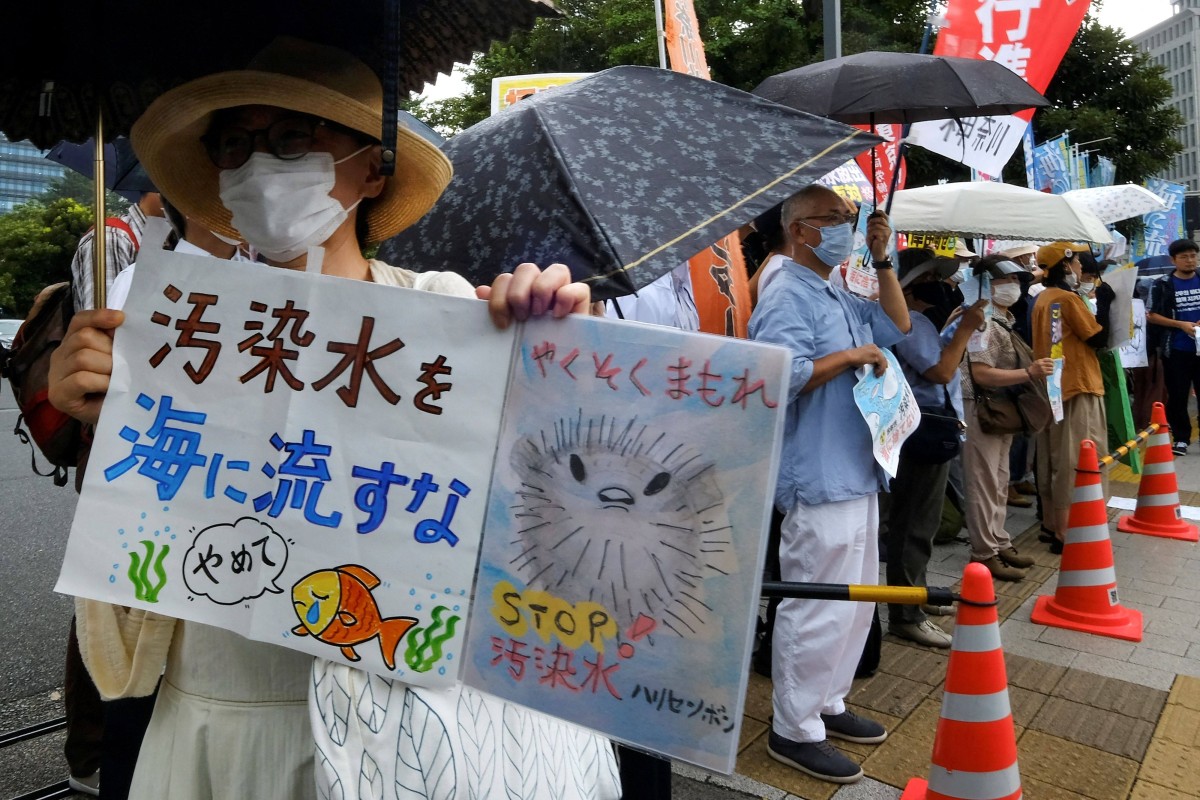

A protester (L) holds signs reading “Don’t throw polluted water into the sea” (L) and “keep your promise” (C) as they take part in a rally against the Japanese government’s plan to release treated wastewater from Fukushima Daiichi power plant into the ocean, outside the prime minister’s office in Tokyo on August 22, 2023. Photo: AFP

A protester (L) holds signs reading “Don’t throw polluted water into the sea” (L) and “keep your promise” (C) as they take part in a rally against the Japanese government’s plan to release treated wastewater from Fukushima Daiichi power plant into the ocean, outside the prime minister’s office in Tokyo on August 22, 2023. Photo: AFPJapan will begin releasing cooling water from the stricken Fukushima power plant on Thursday, 12 years after one of the world’s worst nuclear disasters.

The announcement came despite opposition from fishermen and protests by China, which has already banned food shipments from several Japanese prefectures.

Japan insists the gradual release into the sea of the more than 500 Olympic swimming pools’ worth of water that has accumulated at the stricken nuclear plant is safe, a view backed by the UN atomic agency.

Suzume educates young people about Japan’s devastating 2011 earthquake and tsunami

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida announced the start date on Tuesday, a day after talks with fishing industry representatives who oppose the measure, “if weather and sea conditions do not hinder it”.

The Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear plant was knocked out by a massive earthquake and tsunami that killed around 18,000 people in March 2011, with three of its reactors sent into meltdown.

Since then, operator TEPCO has collected 1.34 million tonnes of water used to cool what remains of the still highly radioactive reactors, mixed with groundwater and rain that has seeped in.

TEPCO says the water has been diluted and filtered to remove all radioactive substances except tritium, levels of which are far below dangerous levels.

“Tritium has been released (by nuclear power plants) for decades with no evidential detrimental environmental or health effects,” Tony Hooker, a nuclear expert from the University of Adelaide, told Agence France-Presse.

This water will now be released into the ocean off Japan’s northeast coast at a maximum rate of 500,000 litres per day.

Environmental group Greenpeace has said the filtration process is flawed and that an “immense” quantity of radioactive material will be dispersed into the sea over the coming decades.

Children of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima nuclear disaster speak up

Japan “has opted for a false solution – decades of deliberate radioactive pollution of the marine environment – during a time when the world’s oceans are already facing immense stress and pressures,” Greenpeace said on Tuesday.

The UN atomic watchdog said in July that the release would have a “negligible radiological impact on people and the environment”.

Many South Koreans are alarmed at the prospect of the release, staging demonstrations and even stocking up on sea salt because of fears of contamination.

But President Yoon Suk Yeol’s government, taking political risks at home, has sought to improve long-frosty relations with Japan and has not objected to the plan.

Yoon last week held a first-ever trilateral summit with Kishida and US President Joe Biden at Camp David, the three united by worries about China and North Korea.

China has accused Japan of treating the ocean like a “sewer”, banning imports of food from 10 Japanese prefectures even before the release and imposing strict radiation checks.

Hong Kong, an important market for Japanese seafood exports, has also threatened restrictions.

Fukushima: A quake, a tsunami, a catastrophe

This has worried people involved in Japan’s fishing industry, just as business was beginning to recover more than a decade after the nuclear disaster.

“Nothing about the water release is beneficial to us,” third-generation fisherman Haruo Ono, 71, whose brother was killed in 2011, told Agence France-Presse in Shinchimachi, 60 kilometres north of the nuclear plant.

James Brady from Teneo risk consultancy said that while China’s safety concerns may be sincere, there was a distinct whiff of geopolitics and economic rivalry in its harsh reaction.

“The multifaceted nature of the Fukushima waste water release issue makes it quite a useful one for Beijing to potentially exploit,” Brady told Agence France-Presse.

Beijing can “leverage a degree of economic pressure on the trade axis, exacerbate internal domestic political cleavages on the issue within Japan ... and even potentially put pressure on improving diplomatic ties between Seoul and Tokyo”.

Naoya Sekiya from the University of Tokyo last year conducted a survey which found that 90 per cent of people China and South Korea thought Fukushima food was “very dangerous” or “somewhat dangerous”.

“I think that’s because Japan hasn’t properly dispelled such concerns,” Sekiya told Agence France-Presse.

“(We) have to make a proper and sufficient explanation.”