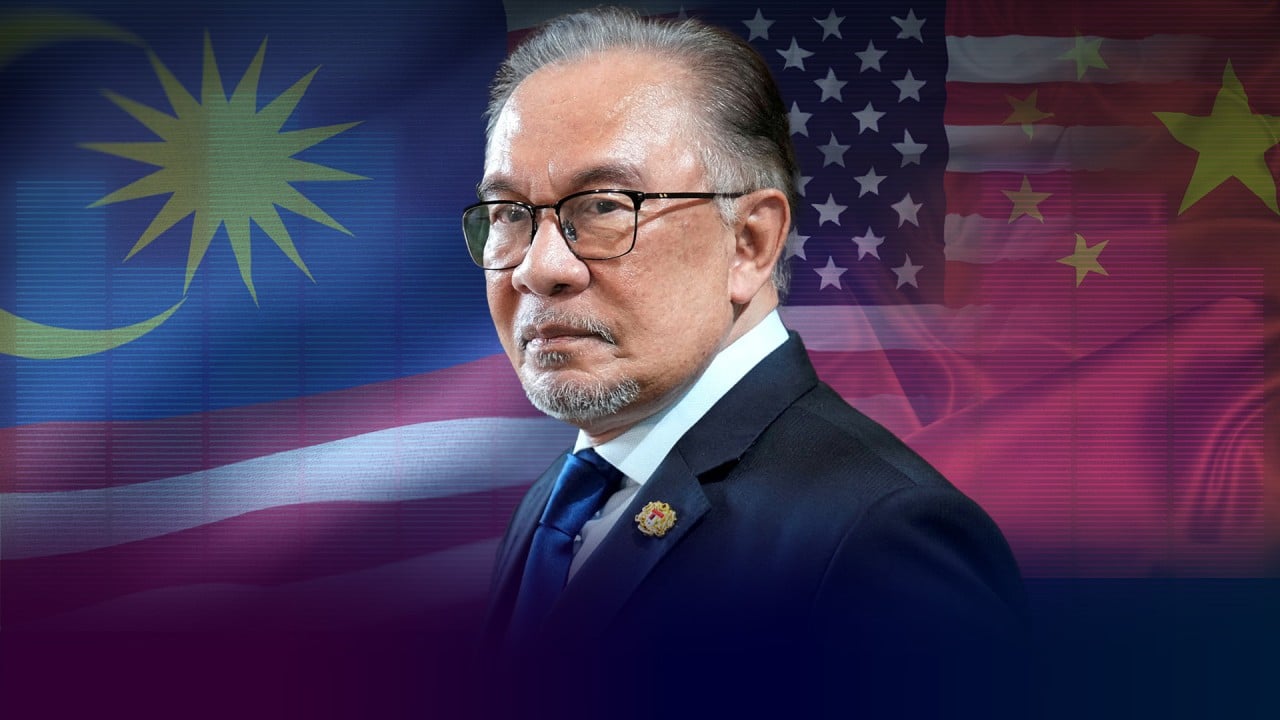

‘Non-aligned’ sanctuary Malaysia reels in Chinese data centres despite geopolitical risks

- Cheap land, low building costs among attractions for Chinese IT companies as Malaysia aims to move up value chain from manufacturing base

Chinese IT service and data centre operator GDS launched its first regional data centre last August in Johor.

Proximity to Singapore and readily available open, cheap land is Malaysia’s winning ticket, experts say, particularly its Johor state which borders the vastly more expensive city state where space is at a premium.

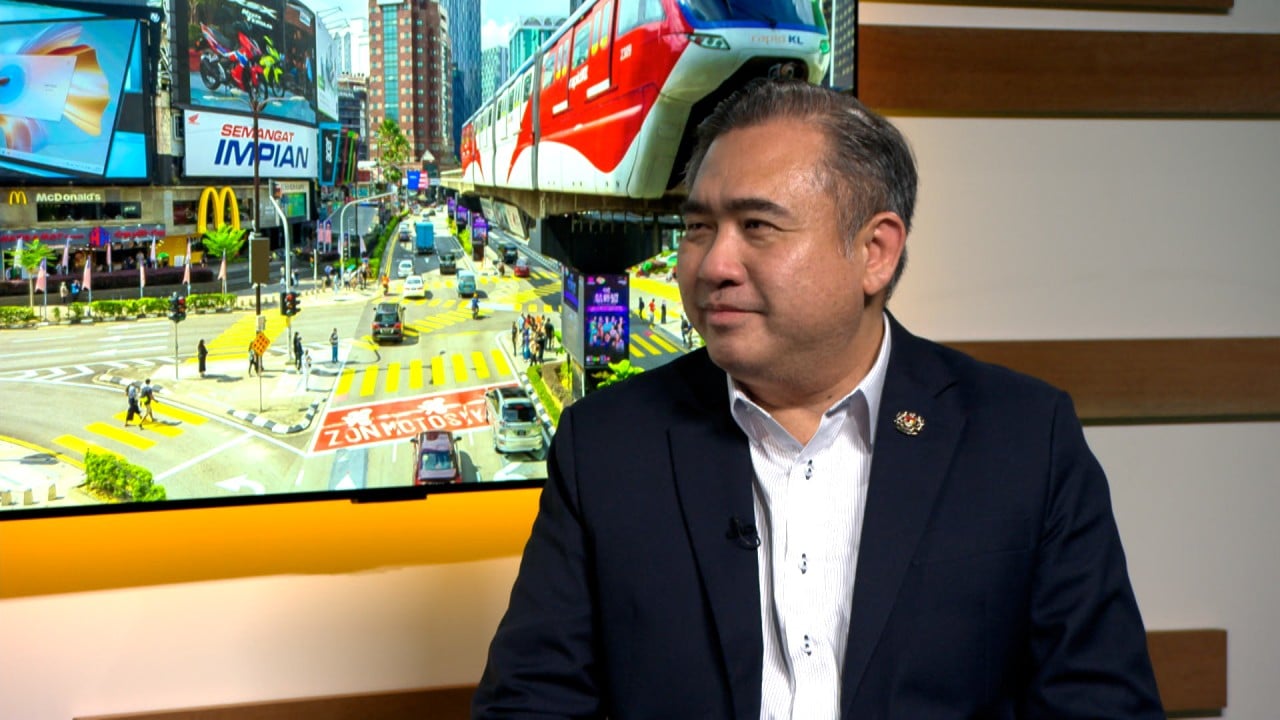

Malaysia’s Economy Minister Rafizi Ramli says his country is courting potential Chinese investors interested in entering the Southeast Asian market.

Malaysia is already a key player in the global semiconductor industry, supplying 13 per cent of total demand in the assembly, packaging and testing sector, according to government data.

Now it is positioning itself as a “non-aligned” sanctuary to do business as geopolitics shapes supply-chain decisions.

This is largely driven by government initiatives such as free zones to meet industrial requirements, as well as the country’s New Industrial Master Plan 2030, which shifts the country’s economic focus towards the digital economy and drives its technology sector up the value chain.

Singapore-based Hinrich Foundation, however, cautioned that China’s global digital expansion introduces risk, amid escalating US-China geopolitical tension, with China framing its data challenges as national security challenges.

In a report on China’s “quest for asymmetric dominance” in data centres published on June 25, the foundation said any restrictions on China’s digital activity going forward by the United States were likely to be treated as threats to China’s security by Beijing.

“In any such flare-up, commercial actors are likely to be caught in the crossfire,” the report said. “So are third-party economies, including those in Southeast Asia, where the US and China compete for influence.”

Report co-author Emily de La Bruyere is also a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defence of Democracies, a Washington lobby group.

For Malaysia, pulling in big tech bets from China and the West is a good hedge in an uncertain world, according to Oh Ei Sun, senior fellow at the Singapore Institute of International Affairs.

“It is quite difficult for either contending side to impose sanctions or boycotts on IT products and services from Malaysia, as they do not have many other alternatives to place their investments,” Oh argued.

There is also the green cost of data centres, which is becoming an increasingly sharp issue, with the potential to erode the clean-energy goals of Southeast Asian nations housing the largest energy-burning centres.

Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB), the sole power provider for Peninsular Malaysia, estimates a growth of up to 130 per cent in global electricity consumption of data centres and AI by 2026, accounting for 2 per cent of the total global energy demand.

In its report from May, TNB said it received more than 70 supply applications from data centre customers with a total maximum demand of more than 11,000 megawatts.

Singapore, with over 70 data centres operating at 1.4 gigawatts, remains cautious of the high energy use of data centres after lifting a four-year moratorium on new data centre builds, emphasising green data centres with lower carbon emissions to support its net-zero targets.

Malaysia-based political risk analyst Adib Zalkapli said aside from the restriction, favourable cost in Malaysia was also another attraction to investors.

“[The lower cost attracts] not just the Chinese but also an Australian data centre in Johor,” Adib said.

The cost of land in Malaysia’s capital, however, costs US$1,471 per square metre compared to over US$20,000 in Singapore, while the cost of construction of a “prestige quality” data centre is US$4 million cheaper per megawatt in the former.