The evolution of the cheongsam: from Suzie Wong to Maggie Cheung, it’s a Hong Kong fashion symbol

The beloved cheongsam, or qipao in Mandarin, traces back to the Qing dynasty but evolved to become a chic dress worn by film stars and socialites

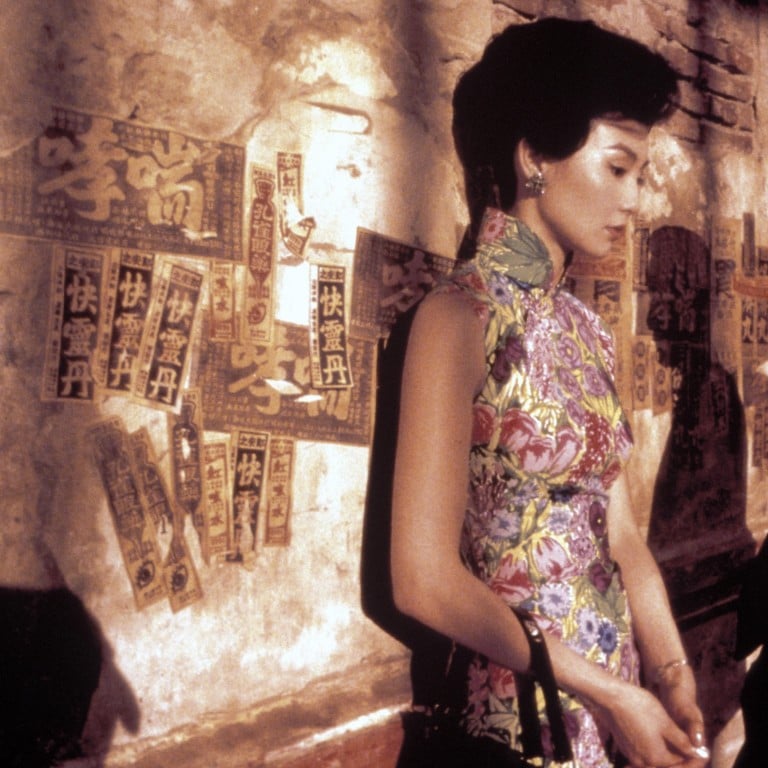

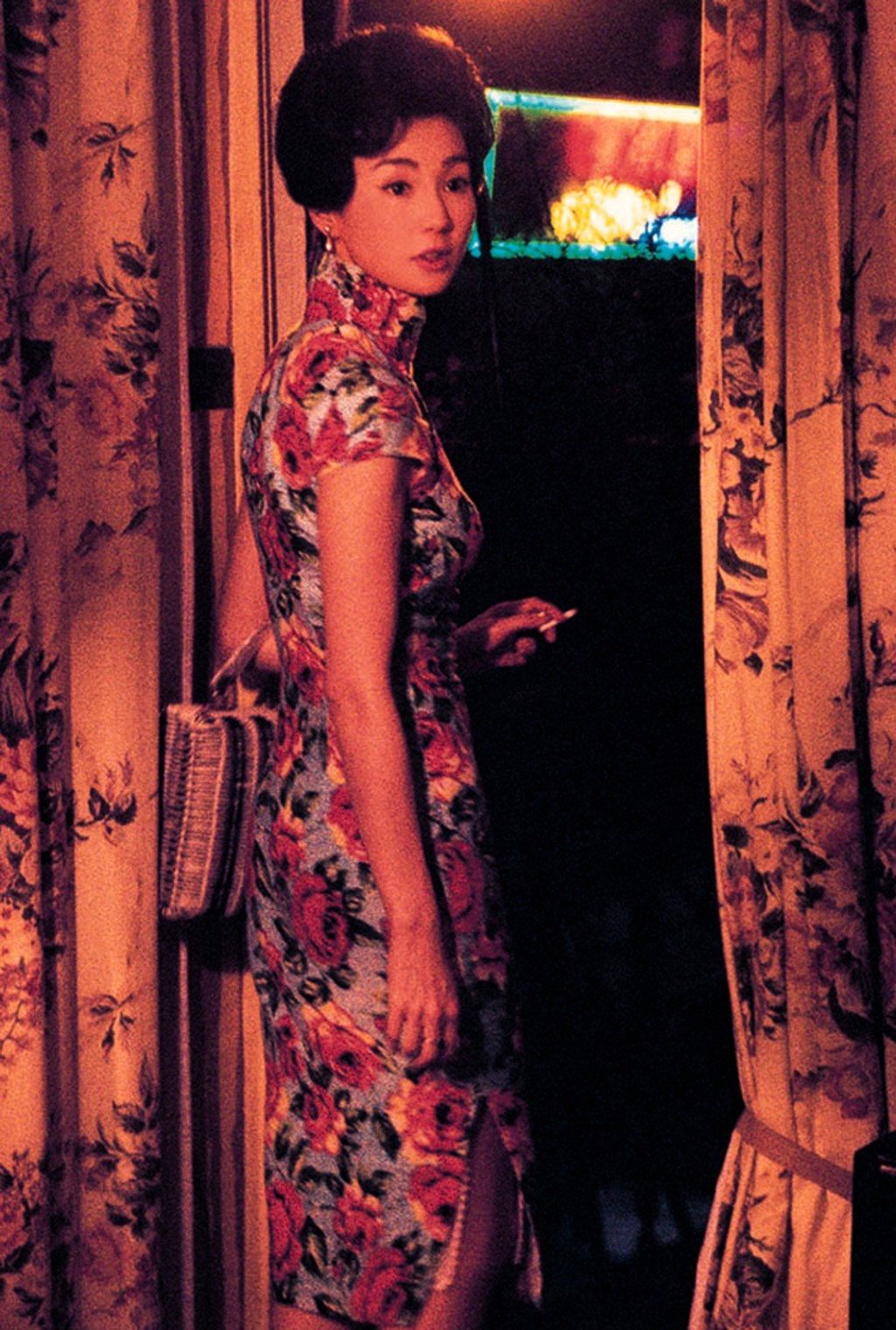

Maggie Cheung Man-yuk firmly seared herself into the collective memory of a whole generation of creatives when, captured by Wong Kar-wai’s seductively soft-edged lens, she emerged over the course of In The Mood For Love in a succession of 21 distinct cheongsam dresses. Each one was so form-fitted to her character, Mrs Chan, that it seemed like she had been poured into them.

Tailored to tightly hug a woman’s figure, the cheongsam is often characterised by a high, starched mandarin collar and asymmetrically fastened at the chest by a series of pankou (knotted buttons)

Depicted among the humdrum miscellany of her claustrophobic flat, or against the weathered concrete facades of pre-war tenements, Cheung’s cheongsam – bedecked in technicolour roses and daffodils, rendered in diaphanous chiffon and structured tweed – only became more resplendent on the silver screen.

Set in 1962, In The Mood For Love was a delicate ode to the cheongsam in its heyday, yet the garment traces its roots to the turn of the 20th century, in a time of immense political and cultural upheaval in China.

The changpao (long robe) of the Qing dynasty had for four centuries served as compulsory dress for the Manchu administrative caste, distinguishing them from commoners yet eventually trickling down to become the national dress for both ordinary folk and the literati alike. Against the backdrop of rapid industrialisation and modernisation, and following the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the coastal city of Shanghai became the first port of call for British, American, French and Russian merchants and diplomats, from whom Western ideals of beauty, such as the flappers of the Jazz Age, quickly took root in the imagination of Shanghai’s upper class.

Soon, the cheongsam (known in Mandarin as the qipao) as we know it began to take shape. Tailored to tightly hug a woman’s figure, the cheongsam is often characterised by a high, starched mandarin collar and asymmetrically fastened at the chest by a series of pankou (knotted buttons).

From the 1940s onwards, however, revised cheongsam designs saw the pankou become a merely decorative feature while a back zip secured the dress for the sake of convenience. Sleeves can range in length from just above the elbow to no sleeves at all, although fitted cap sleeves that just cover the shoulders are the most popular option today. Lengthwise, history has seen the cheongsam range from floor-length to below the knee, and given the narrow, fitted nature of the garment, side slits were essential to allowing a degree of movement while flashing a bit of skin.