Chinese property downturn hitting land-dependent local governments hard

Andrew Collier says a downturn in China's land and property market is cutting off local governments' cash tap, and will leave them struggling to honour their spending obligations

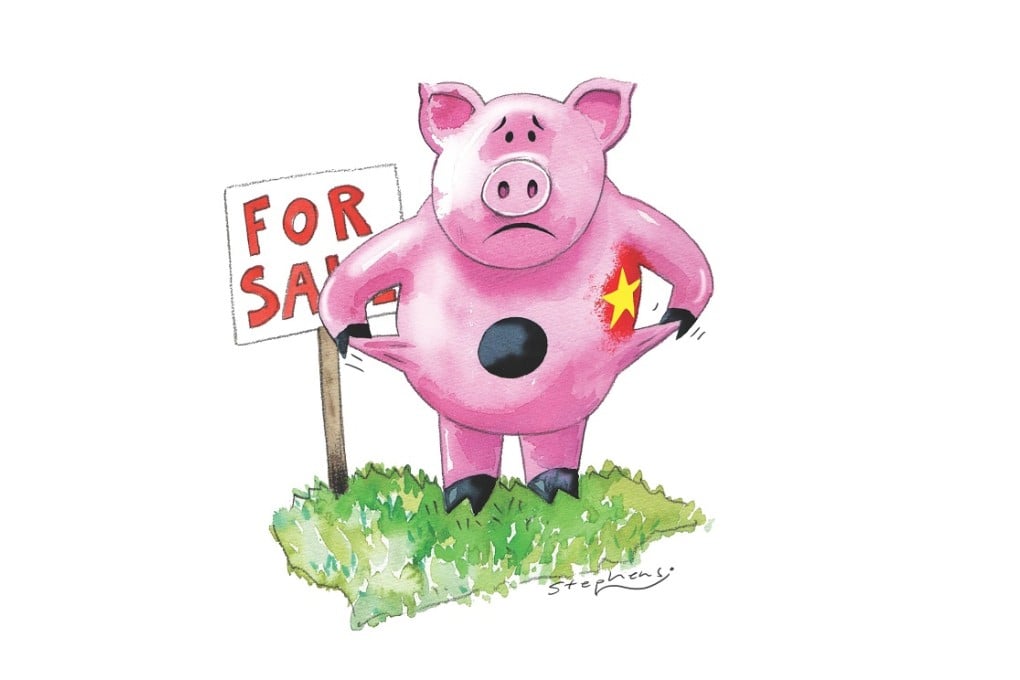

For the past decade, land has functioned as a giant piggy bank for China's cash-starved local governments. Whenever they ran short of funds to pay for anything, from pensions for retired steelworkers to eye exams, there was usually a piece of land ready to put on the market. Unfortunately, the piggy bank is running on empty.

In 100 Chinese cities tracked by the research institute China Real Estate Information, the volume of land sold fell 47 per cent for the third quarter this year. Revenue dropped a shocking 75 per cent, with prices down 52 per cent. For the first time in years, when they put up land for auction, local governments suddenly found themselves with unsold parcels. In the past six months, almost 20 per cent of land for sale failed to find a buyer.

Take Chengdu , the capital of Sichuan province. In the first seven months of this year, Chengdu offered 19 units of land for sale. Six failed to find buyers and the local government terminated the auction of three others. "This has never happened before," said a local developer with over 15 years of experience in Chengdu's housing market. "Almost everyone was shocked by the result. We have prepared for gloomy data but never expected one-third of failed land sales like this."

The main cause of the decline is reluctance by property developers to pay the high prices requested by the local governments. There is a "cat and mouse" game going on between governments and developers. The local governments are hoping for a second fiscal stimulus to prop up prices, while the developers are waiting for the governments to acknowledge that China's housing boom is coming to an end and they need to lower the offering price.

The data on land sales suggests the downturn is going to be a lot worse than anyone had expected. Worse yet, land is a fundamental part of China's economy, and the collapse of land sales is going to have a knock-on effect throughout the country.

First, China's overall gross domestic product has been driven a good deal by the property sector. Estimates vary, but according to research from Nomura, last year property accounted for 16 per cent of GDP, 33 per cent of fixed asset investment, 20 per cent of outstanding loans, 26 per cent of new loans, and 39 per cent of government revenues. The mild slowdown in the property sector looks like it will be much worse in the future once the chain of construction, starting with land sales, filters through the economy.

But the bigger problem is likely to be felt by local governments. Until 1994, local governments kept the bulk of tax revenue collected from businesses and residents. That year, though, then premier Zhu Rongji struck a deal to centralise tax receipts back to Beijing with an agreement to remit funds to the local governments. However, with the gradual collapse of state firms, who had been providing social services to their workers, along with rising promises by Beijing to its citizens, local governments faced a growing gap between revenue and expenditure.