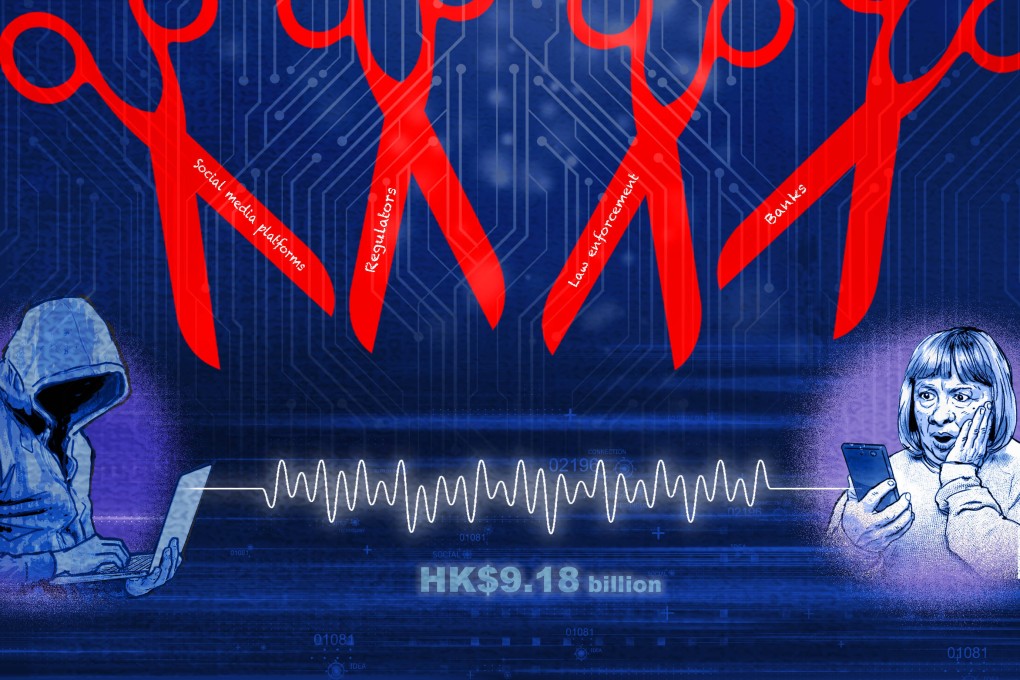

Hong Kong regulators, banks struggle to contain damage from financial fraud

- Fraud nearly doubled last year, putting the city of 7.5 million people at the top of the world in per-capita losses

In the first of a two-part series, Aileen Chuang looks at what Hong Kong’s financial regulators, banks and social media network operators must do to stamp out scams.

Lee’s credit cards and bank account had been frozen, the callers falsely asserted, because she had provided inaccurate data when she tried to unsubscribe an insurance policy on WeChat’s wealth management platform. To free her account, she had to raise her daily remittance limit to HK$1 million (US$128,000) and make a handful of transfers to verify her identity, the callers said.

To prove their bona fides, the callers attached numerous photographs and documents: certifications by China’s securities watchdog, the coverage contract of one of China’s largest state-owned insurers PICC, as well as chat records with bank staff and with a chatbot operated by UnionPay, the payments network.

They were all fake. The entire scheme was an elaborate ploy to trick Lee into transferring money to a confidence trickster. After phone calls that totalled four hours, Lee found herself poorer by HK$570,000.

Lee was the victim of a phone scam. In Britain, this type of Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud will compel the bank involved to compensate her when a law comes into effect on October 7.

Not in Hong Kong. Lee, an office worker in her early 30s, has no recourse to recover her money because she had authorised her push payment, albeit into a scammer’s account.