Advertisement

Advertisement

Prof Zhang Jun

Zhang Jun is dean of the School of Economics at Fudan University and director of the China Centre for Economic Studies, a Shanghai-based think tank.

The country has all the tools – and resilience – it needs to adapt to its new geopolitical environment and accelerate the domestic transformation.

Beijing has shown its commitment over the years to constant adaptation and structural reform that sets the stage for balanced growth.

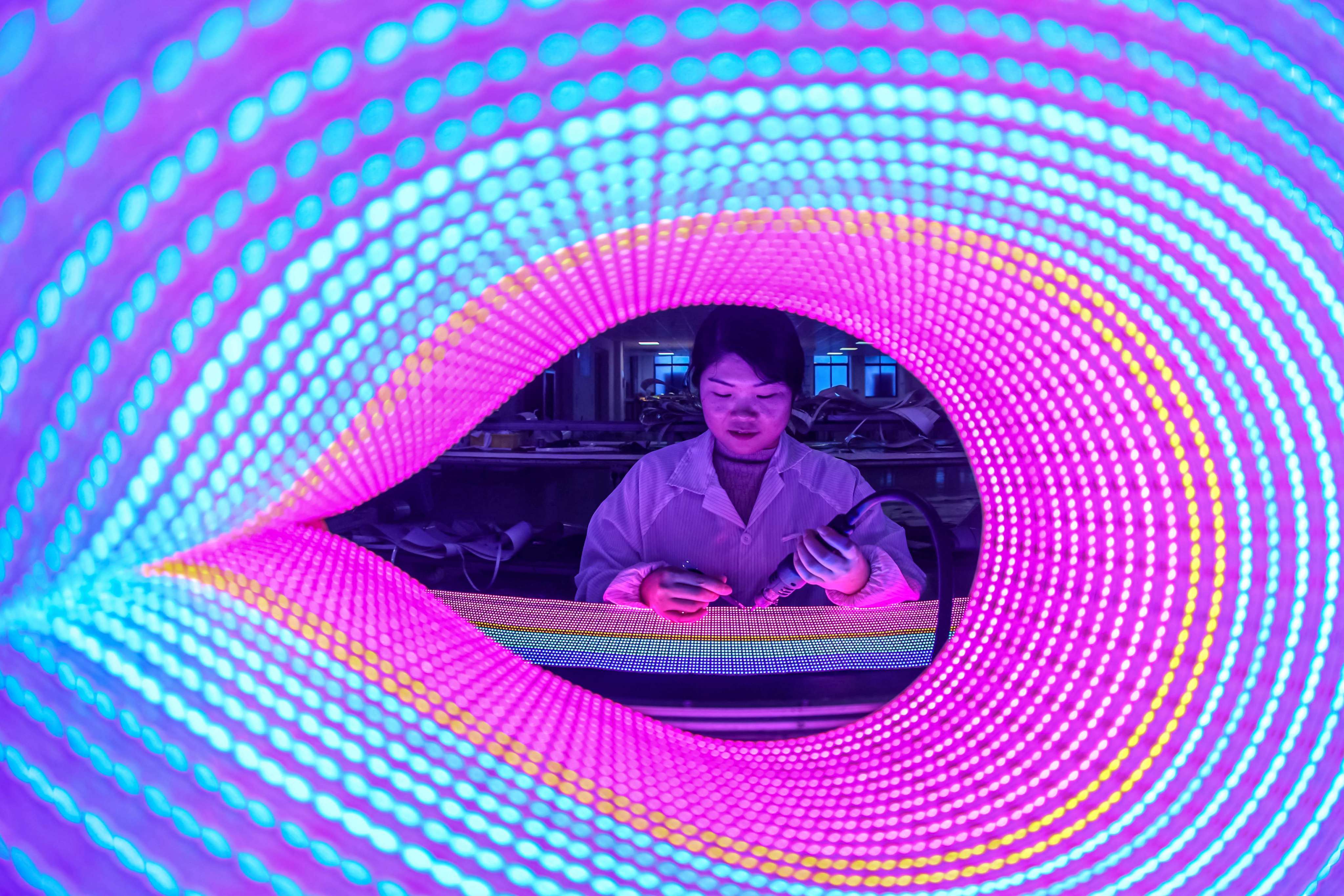

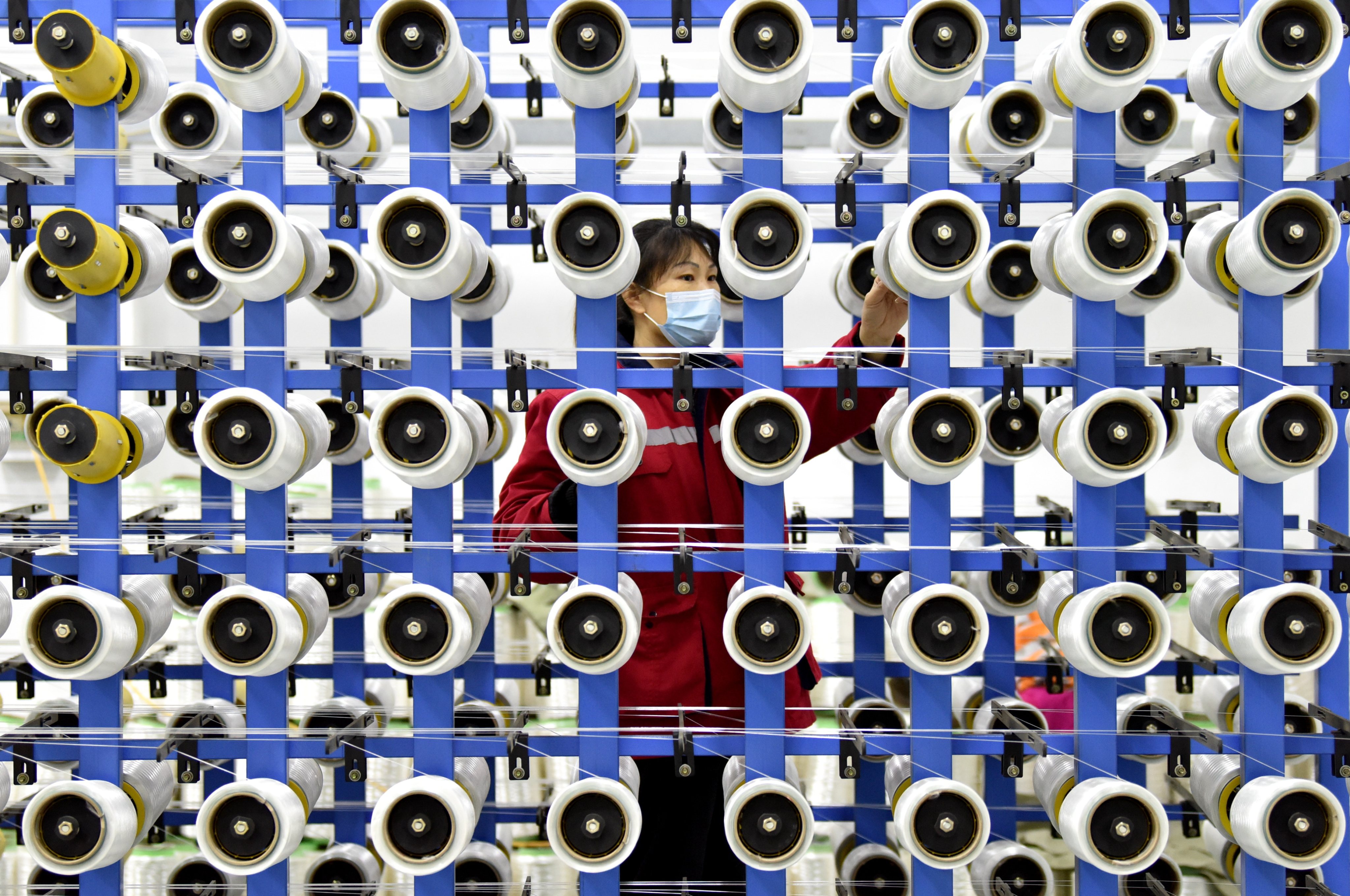

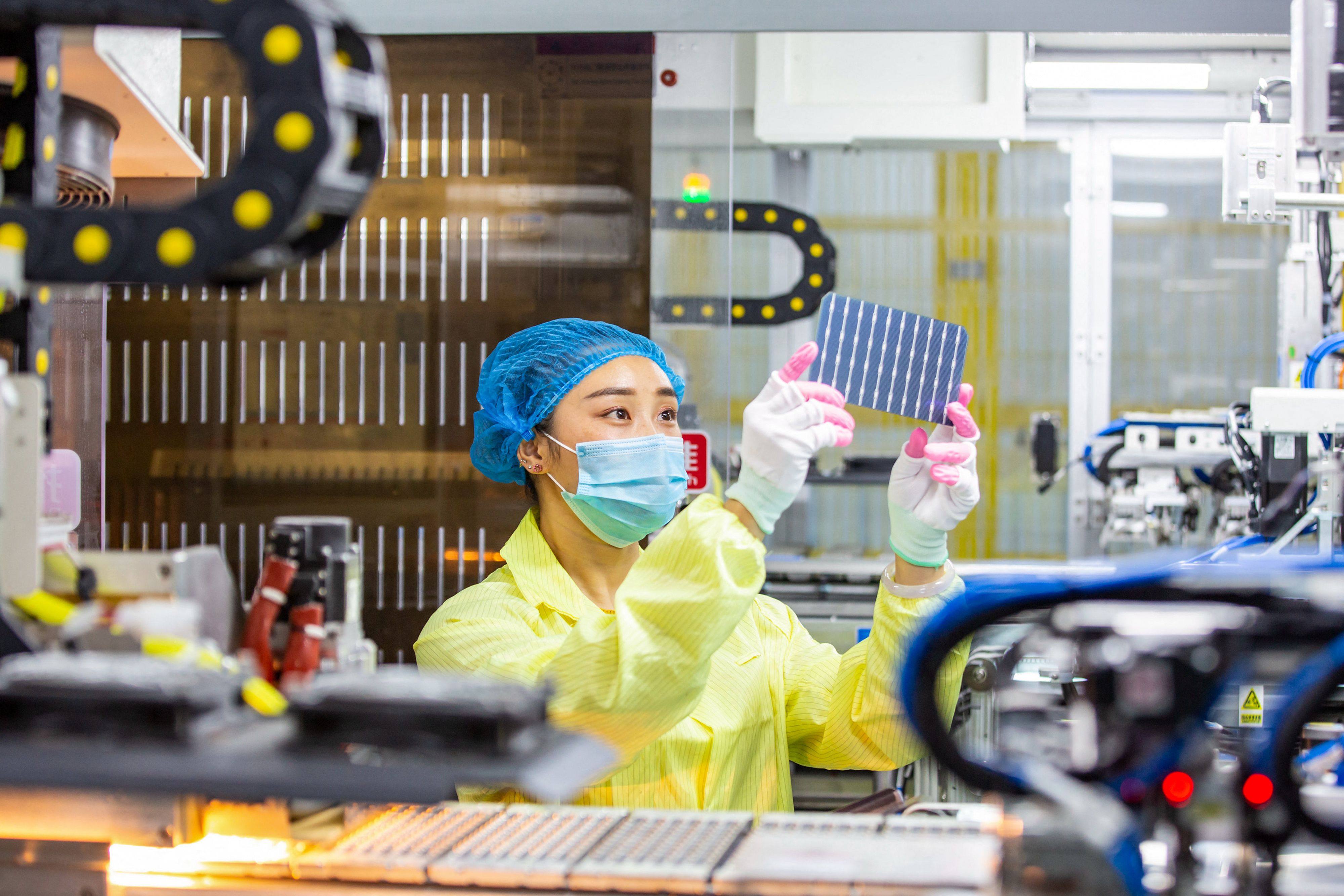

China has achieved economic success not just through repurposing Western technology but by rapidly upgrading and adapting it. Top-down management coexists with local autonomy and bottom-up innovation in the Chinese industrial ecosystem.

A new book by MIT professor Yasheng Huang suggests China’s political economy has long operated under a mix of autonomy and control. The nation’s development strategy has largely reached its limits and Beijing must now harness its innovative potential to spur its ‘animal spirits’.

Advertisement

The impact of “decoupling” is probably overstated, and supply-side structural reforms have improved domestic resilience. The economy’s current status has made rebalancing possible and also created a sense of urgency that could benefit the country.

Beijing’s move away from aggressive macroeconomic policy goes back to ‘de-risking’ efforts that began in 2016. However, the growing risk of a protracted downturn underscores the need to find more effective solutions to the pressing economic challenges.

China will continue to reap the benefits of its shift from a growth-first mindset to a focus on job creation, which is more conducive to the implementation of structural reforms and the adoption of new technologies.

Stuck at home during repeated lockdowns as part of the country’s zero-Covid policy, Chinese households amassed trillions in savings last year. Some are pinning hopes of economic recovery on ‘revenge spending’, but those savings could be a sign of uncertainty rather than pent-up demand.

Western observers tend to attribute China’s rapid growth to market reforms, but this downplays the crucial role of the state as a driver of economic success. China’s trajectory highlights the power of a capable, dynamic political elite to drive prosperity.

Local-level innovation is not incompatible with the implementation of the national Covid-19 policy framework. In the longer run, local officials’ appetite for policy innovation, experimentation and adaptation holds the key to China’s economic dynamism.

As China’s 5.5 per cent annual growth target drifts out of reach, the government is turning to investment to boost the economy. But with imported inflation already threatening to drive up consumer prices, Beijing is wise to avoid making matters worse with excessive stimulus spending.

China’s outbreak response system has evolved to serve a population with a large number of unvaccinated elderly and address regional disparities in social services and healthcare. The strategy is characteristic of Chinese policymakers’ willingness to incur short-term high costs to advance long-term development goals.

Perhaps the greatest impact of the US effort to contain China has been to clarify China’s weaknesses and spur more progress in addressing them. US policies will not force China out of the existing global economic system, let alone lead it to embrace an insular, state-controlled development model.

If barriers to migration grow high enough, populous countries will outpace smaller ones in innovation, even the richer ones. If China makes the most of this advantage, the US will find it all but impossible to hamper its economic progress.

While foreign firms might arrive in China with a slight technological advantage, it is usually short-lived, given how fast Chinese companies learn. This base-level dynamism has been strengthened by the government’s investment in the internet, communication, transport and logistics over past 20 years.

The problem with many predictions about China’s economy is that they failed to include the variable of size. The growth of China’s bond market, the renminbi’s internationalisation and the emergence of the e-CNY show China’s rise will be faster than many expect.

The shift in sentiment towards China is partly rooted in ideological polarisation, which has impeded US leaders’ ability to govern effectively. Back when voters shared the same facts, politicians could appeal to the ‘median voter’. But the fragmenting of the US media landscape has changed the picture.

China’s rapidly declining fertility reflects the legacy of family planning policies, which had caused the birth rate to plummet well below replacement level by the 1990s. If it is to sustain its economic dynamism, it must expand its labour force by raising the retirement age and encouraging families to have more children.

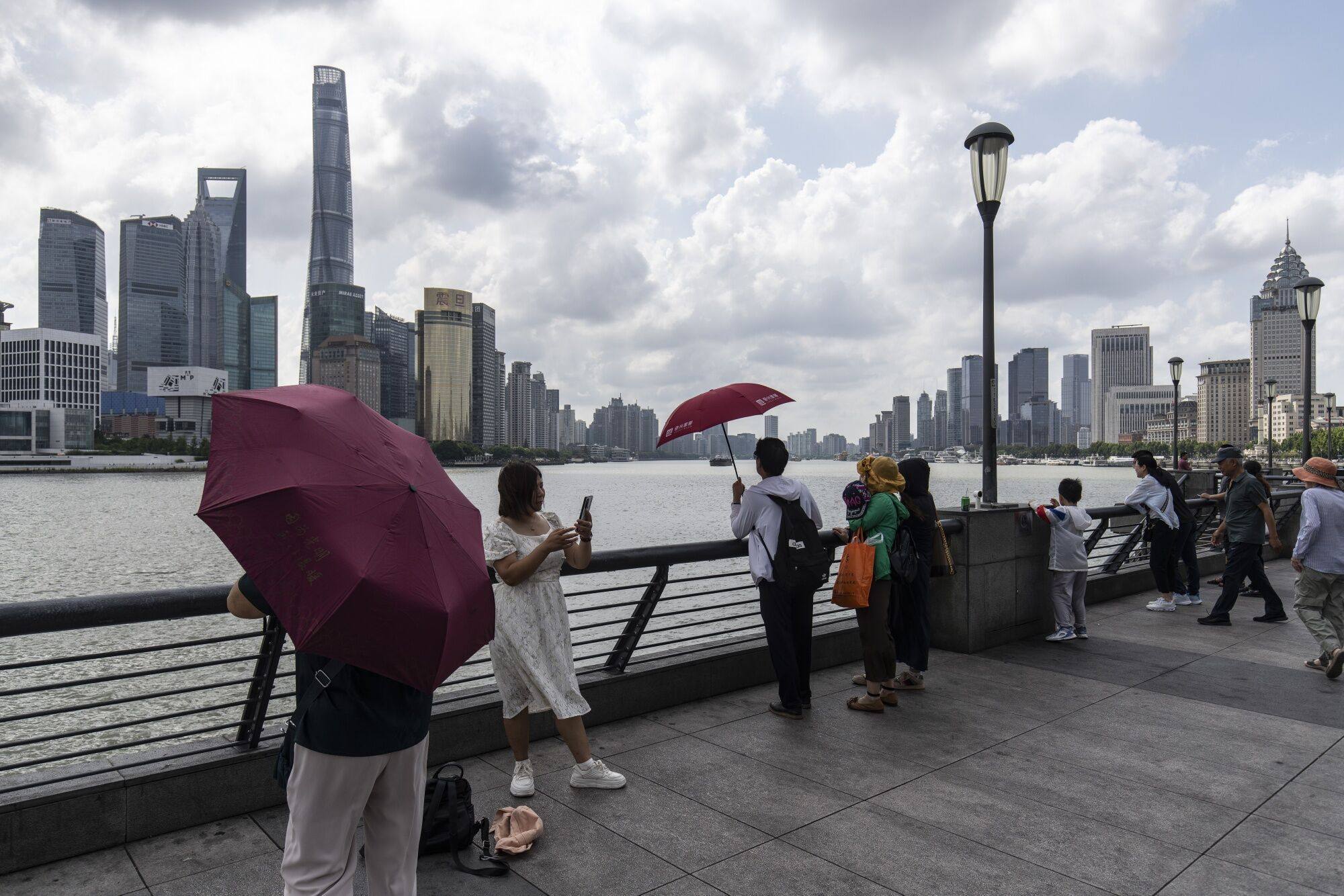

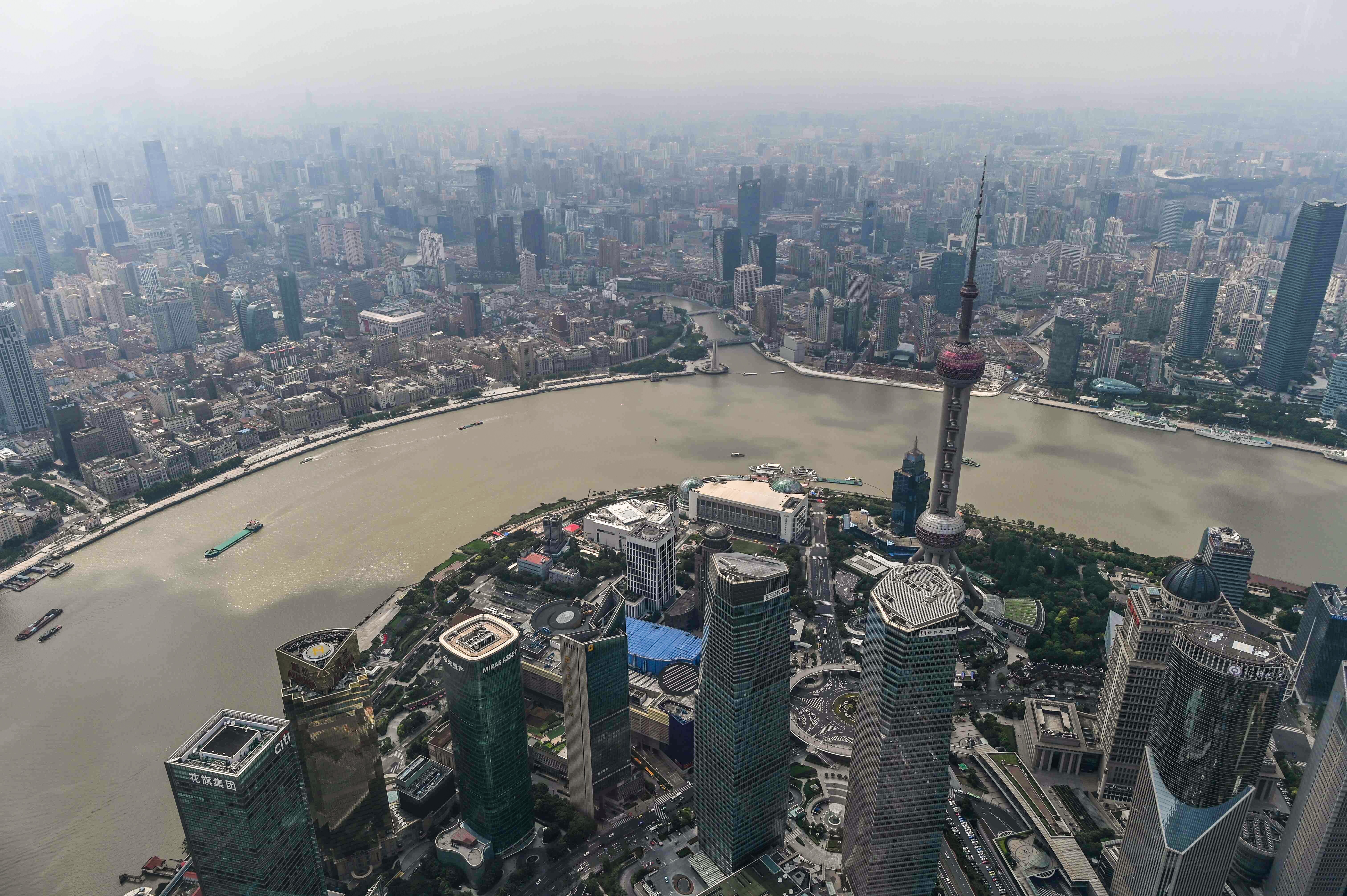

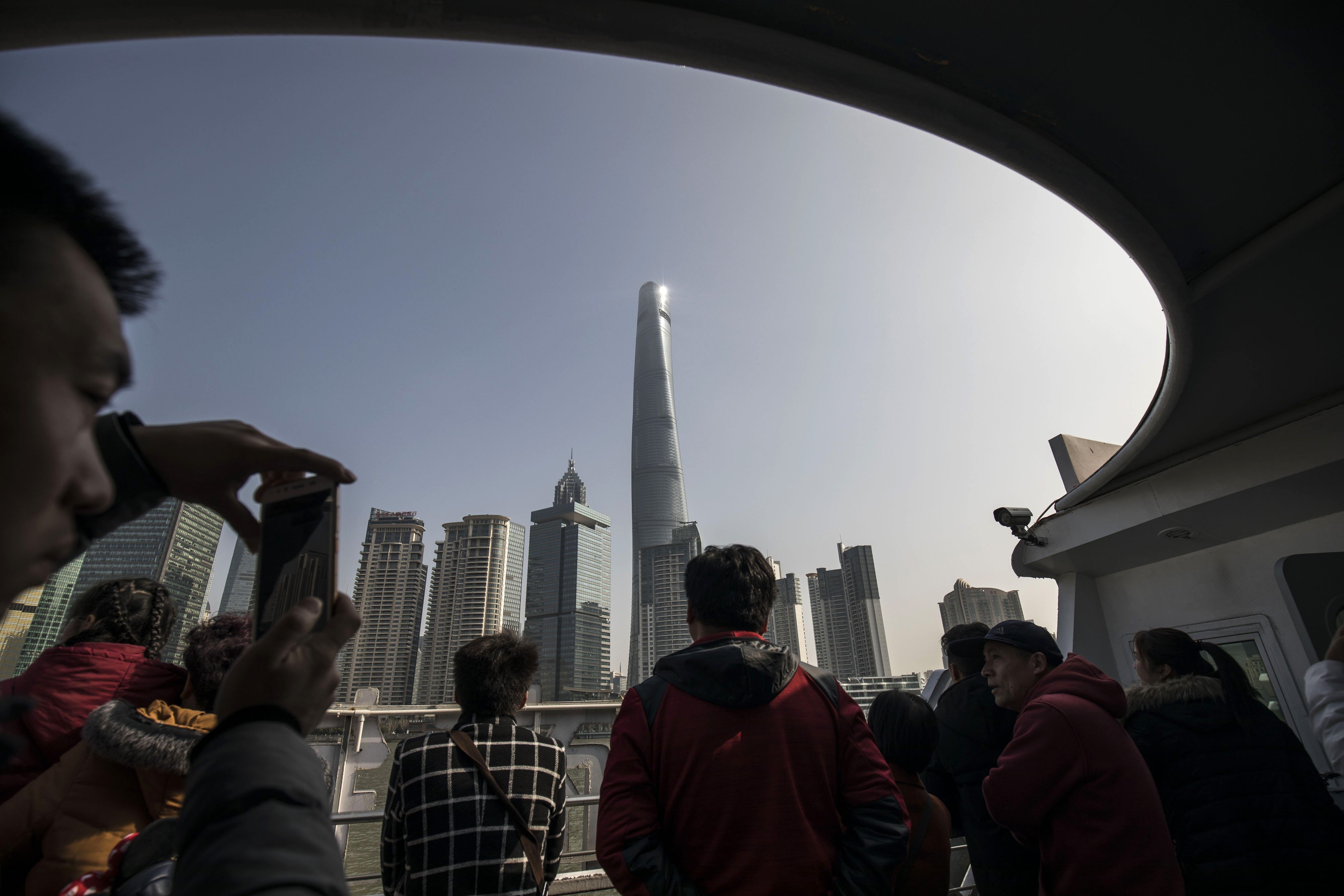

Major cities such as Shanghai and Shenzhen are vital to China’s economic future, but none are more important than the other as each has a unique role to play. By recognising and investing in the strengths of pioneering cities and regions, China has built a powerful mechanism for driving its economic transformation.

In China, the coronavirus pandemic has accelerated the uptake of digital technologies in households, schools and companies. Technology has also enabled the country to emerge from Covid-19 lockdowns without risking public health.

It is naive to believe that technological decoupling, trade sanctions or forced supply chain changes will end China’s economic expansion. The world has yet to appreciate the significance of China’s inward shift of economic gravity.

China’s role is changing, without a doubt, as the economy shifts gear into developing its hi-tech and services sectors. Its innovation, and still considerable manufacturing heft, will ensure it has a place in the global value chain.

The epidemic may well reach a turning point in the next two weeks, confining the worst of the economic impact to the first quarter. This, and policy adjustments, should allow China to record economic growth of 5-5.5 per cent for the year, firmly back on track.

Disruptive policies in environmental regulation and debt management, for example, hurt investor confidence, stymie reforms and contribute to China’s economic slowdown. For long-term stable growth, Beijing needs to eventually let go and get out of its own way.

To reach its centenary goal of being a ‘great socialist country’, China needs another three decades of strong growth. This is possible only if it transforms its growth model to spur a sharp and sustainable increase in home-grown demand.

Beijing’s willingness to liberalise and reform has allowed local-level competition and experimentation to flourish into the fiscal federalism that is the main driver of its economic rise.

China has not deployed all its trade war weapons, not because it doesn’t have them, but because it sees stability as preferable both at home and abroad. Likewise, it would prefer gradual reform.

Serious challenges on several fronts did not deter the authorities from pressing on with a commitment to change the Chinese growth model. The story of how these efforts contributed to the rise of the middle class and the emergence of a world-leading digital economy demands a fuller understanding.

Opening up markets – from telecoms to education and insurance – would be a massive boost to an economy struggling with declining productivity and a trade war.

China’s economic structure, its development stage and pending reforms mean growth will remain consistent. Frequent comparisons to the collapse of the USSR and stagnation of Japan are therefore inadequate.