How a masturbating monk and ‘Korea’s Obama’ drove Seoul to say ‘Me Too’

In South Korea, the campaign against sexual harassment has taken down a presidential hopeful and a freedom fighter turned poet who once had hopes of a Nobel Prize. In a notoriously patriarchal society, where will it end?

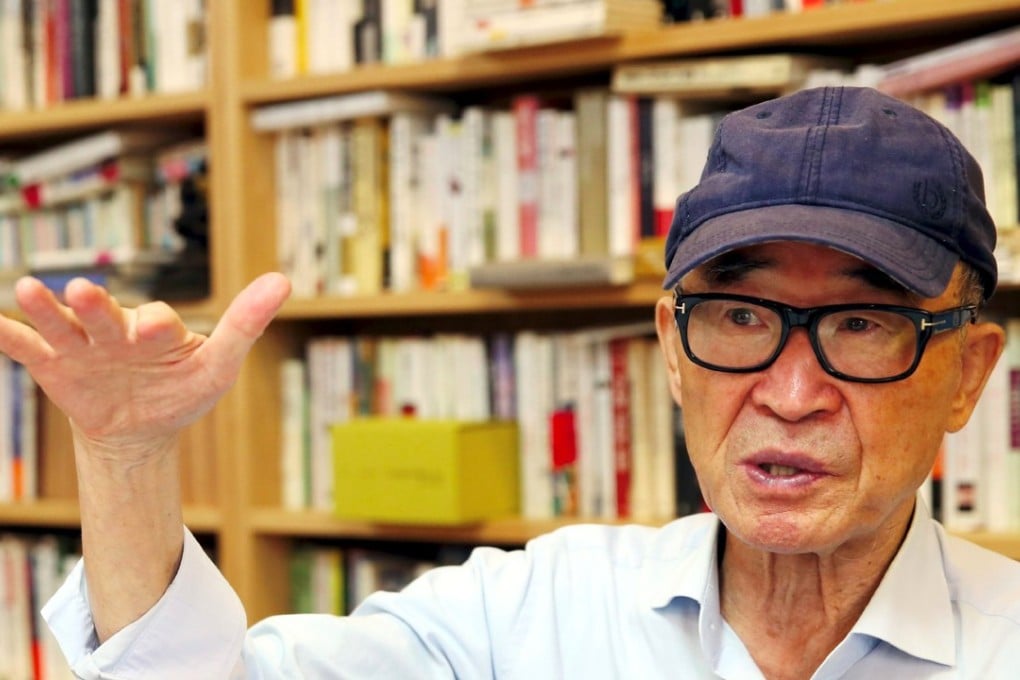

“I have done nothing that might bring shame on me or my wife,” the poet Ko Un said on Monday, breaking a month-long silence after being accused of masturbating in public and using his literary influence to coerce young writers to have sex with him. The allegation shocked and saddened many. Ko is a Buddhist monk, a former freedom fighter, and has long been the country’s greatest hope for winning its first Nobel Prize in Literature. Now, he has also become the most high-profile case in its Me Too movement, though some have said his crimes were an open secret. “Let’s be honest,” the poet Reu Keun said. “How many of us … did not know about Ko’s atrocities?”

Is South Korea ready to take on racism? First, it must admit it exists

Many said something similar when allegations of sexual harassment surfaced against Harvey Weinstein, the insufferable Hollywood producer whose alleged bad behaviour prompted the Me Too campaign in the first place. But in America, some have found their loyalties divided as a string of allegations surfaced against other, more likeable personalities – leading to what The New York Times called the “Louis C.K. Conundrum”, in reference to a comedian who has admitted numerous transgressions.

In South Korea, few have been breaking out the violins for Ko, revered though he was. As a pacifist revolutionary poet Ko enjoyed a place in society roughly comparable to that of Martin Luther King Jnr and for a society as patriarchal as South Korea, the downfall of a man so highly revered is striking.

Compare this to the way the Me Too movement has played out elsewhere in Asia, where denial has been commonplace. In China, the state-run China Daily has claimed such problems are largely unknown because of the country’s superior cultural values; in Japan, the writer Shiori Ito wrote for Politico: “It’s not that victims haven’t come forward; Japanese society wants them to stay silent.”