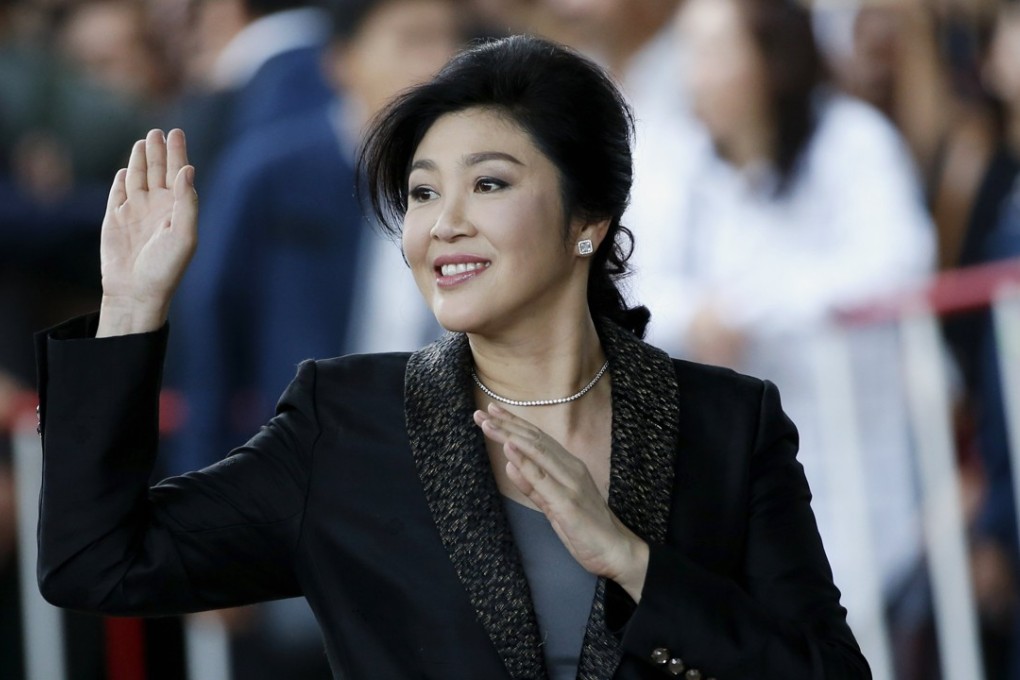

Don’t cry for me, Shinawatra: why Yingluck’s bad luck is good for Thailand

The self-imposed exile of the former prime minister opens a window of opportunity for the powers-that-be on all sides in Thai politics to break the vicious cycle of coups, constitutions, elections, coups

Had she appeared in front of the Supreme Court’s Criminal Division for Political Office Holders on August 25 and ended up in jail, Thailand’s political temperatures would have heightened markedly. Instead, Thai politics has reached a crossroads after nearly two decades of topsy-turvy instability and turmoil. Whether the country can transcend its “yellow versus red” polarisation to regain its footing will depend on the willingness of its old and new elites to play by the rules and stick to the electoral arena to determine outcomes.

Thailand chases Chinese money, but at what cost?

In the eyes of his sceptics and the supporters of the 1997 charter, Thaksin had to know that his money was registered under his servants’ names, despite arguing that his wife was responsible for administrative family matters. Many thought that the NCCC’s overwhelming indictment could not be reversed. But Thaksin had the tide of Thai politics going for him at the time. He rose to the premiership promising to kick out the International Monetary Fund and restore Thai economic potential after the devastation and lost national pride from the 1997-98 economic crisis. His TRT-led government had innovative and so-called “populist” policies to boost the grassroots for economic growth through consumption as well as exports. His critics were a small minority. Most people, including many who would later turn out to be his adversaries, were pulling for him.

The Constitutional Court fudged the verdict with an 8-to-7 count. Seven judges ruled Thaksin guilty, the other eight were split. Half concluded he did not know about the hidden assets and the other half said they had no jurisdiction over the case. The decision politicised the 1997 constitution and catalysed Thailand’s democratic downfall. The Constitutional Court lost credibility, whereas the NCCC became marginalised. Not long after, Thaksin absorbed smaller parties and made Thai Rak Thai into a juggernaut, winning re-election in February 2005, this time with 77 per cent of lower house seats.

Teflon Thailand’s economy gets a boost as Chinese tourists return

This is where Thai politics encountered a major turning point. After his February 2005 victory, Thaksin became as unstoppable as he was overconfident. A mutual antagonism soon emerged between him and established centres of power which had earlier given him the benefit of the doubt. Brinkmanship ensued. Thaksin was as hubristic and defiant as his opponents were self-righteous and vindictive. Limited street protests from August 2005 expanded into the yellow-clad People’s Alliance for Democracy after Thaksin sold his family-owned Shin Corp for 73 billion baht in January 2006, completely tax-free. Thaksin’s sins of graft and conflicts of interest were suddenly exposed. It was an ugly period in Thai politics that eventually ended with a putsch on September 19, 2006. Thaksin was on the back foot, and he kept back-pedalling while staying inside democratic boundaries. Had his opponents not seized power and instead dealt with him in the electoral arena, Thai politics and its fledgling democratic system under the popular 1997 charter might have had a chance for maturation and consolidation.