What China’s Belt and Road has to learn from 1920s America

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s plan to resurrect the Silk Road must heed the lessons of a bygone era

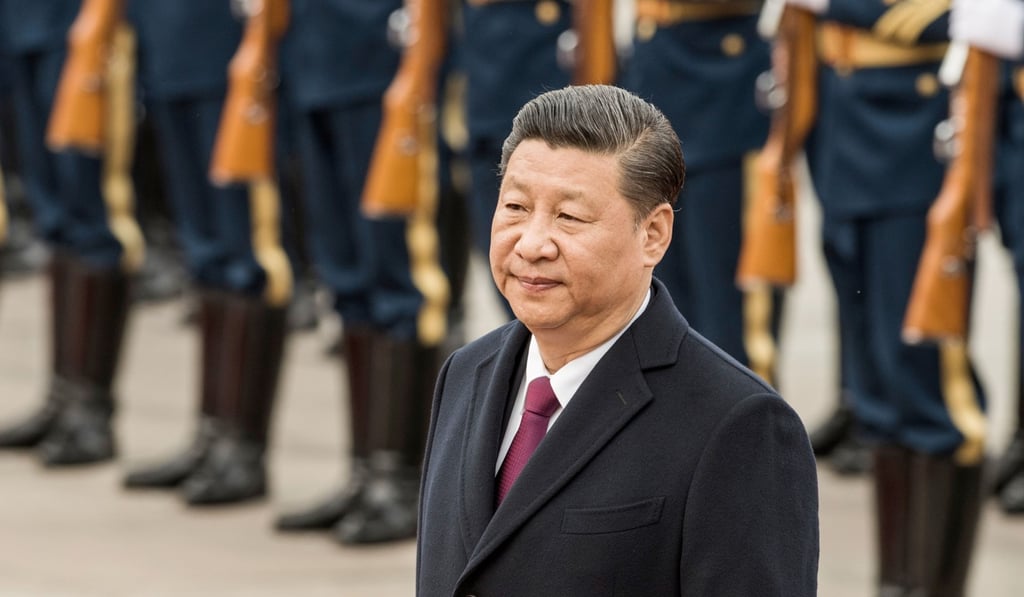

Perceptive China-watchers have observed that President Xi Jinping ( 習近平 ) has modelled his political mission on Deng Xiaoping ( 鄧小平 ) – even if his methods bear a whiff of Maoism.

Deng put an end to the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution and engineered China’s transformation towards socialist modernisation. Xi’s sweeping reforms and anti-corruption crackdown aim to engineer an analogous transformation that will deliver China to the cusp of a “moderately prosperous” society by the time of the Chinese Communist Party’s centennial founding in 2021.

No single political project personifies this more than the “Belt and Road Initiative”, which aims to resurrect the ancient Silk Road through infrastructure projects that will link Eurasian economies into a China-centred trading network. When two dozen or so heads of state assemble in Beijing for the Belt and Road Summit on Sunday and Monday, the magnitude of the imposing soft-power dimension of this “win-win” project that aspires to embed Xi’s “China Dream” within a “neighbourhood community of common destiny” will be on ample display. The BRICS Summit in Xiamen (廈門) this September will be a sideshow by comparison.

Puffing across the ‘One Belt, One Road’ rail route to nowhere

A variety of malignant motives, mainly economic, have been ascribed to the Belt and Road plan. It aims to channel Beijing’s allegedly manipulated reserve surpluses abroad, prop up the internationalisation of the yuan, unload China’s industrial overcapacity on neighbours, ensnare the recipient country in a cycle of debt, exploit the host country’s strategic resources and purchase their political affiliation along the way.