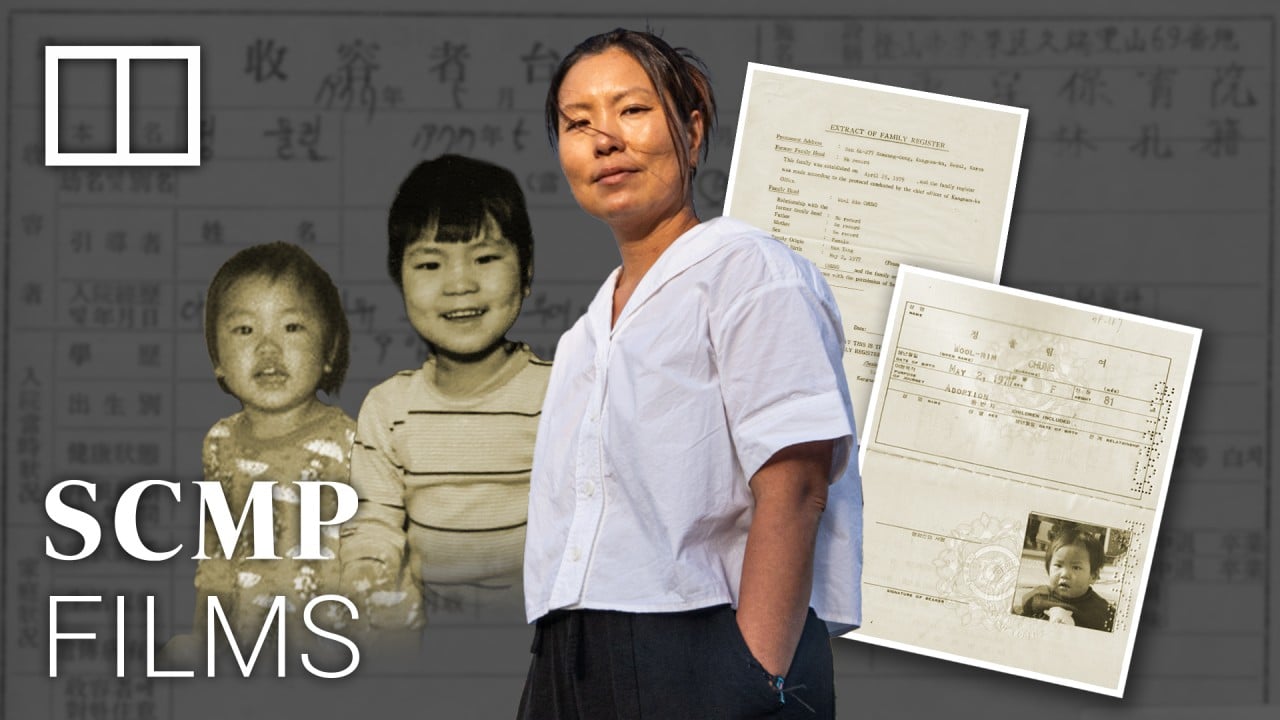

South Korea’s dark past as West’s ‘baby farm’ laid bare by adopted ‘children for sale’ who grew up far from home

- More than 170,000 South Korean children were adopted by Western families in the turbulent post-war period – nearly 9,000 a year at times in the 1980s

- Many were labelled orphans, despite their birth parents still being alive, and say their documents were falsified, making them question their identity

16:32

‘Children for sale’: inside South Korea’s dark past as the West’s ‘baby farm’

It was late spring and Uma Feed had just dropped her son off at a kindergarten in Oslo when her phone rang unexpectedly, bringing news she’d been searching for her whole life: the true identities of her birth parents.

A long letter and video message followed, revealing that Um Sul-yung – the name given on Feed’s adoption documents – was actually given up for adoption by her grandparents without the consent of her mother, who was hospitalised with tuberculosis at the time.

“Every evening, my mum and my older brother had gone out to look for me. They were just wandering the streets,” she said.

As it turned out, nearly all the information she’d received from the Norwegian adoption organisation was inaccurate, Feed told This Week in Asia. In response to queries, the organisation said it couldn’t comment on her case, citing privacy laws.

Feed, who legally changed her first name to Uma in her twenties after rejecting the Norwegian one her adoptive parents had given her, is just one of the more than 170,000 South Koreans who were taken in as children by Western families in the decades following the Korean war.

And experts fear her story – of betrayal, deceit and the long search for the truth – is far from unique.