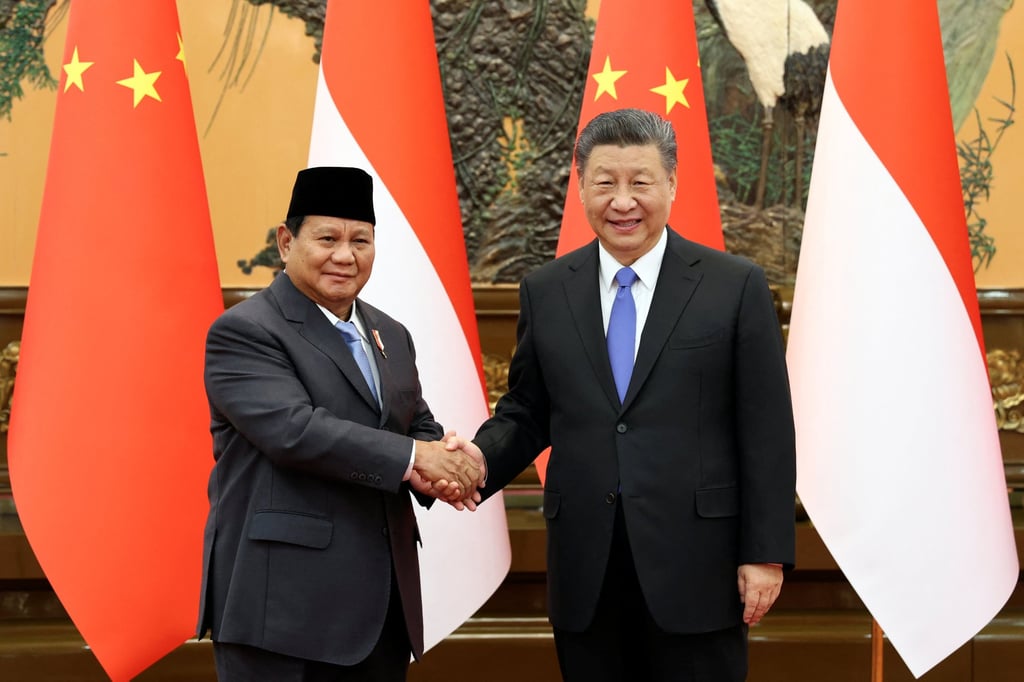

Asian Angle | Will Indonesia’s foreign policy be more assertive under Prabowo?

Prabowo Subianto is expected to be more hands-on in managing Indonesia’s foreign policy than his predecessor Joko Widodo

As Prabowo takes over, three key areas bear watching: positioning, preoccupations and personalities.

The first issue is how Prabowo wishes to position Indonesia, vis-a-vis not just the US and China but also powers like Russia, Japan and the European Union. Most commentators and scholars see Prabowo as an arch nationalist and a realist who believes that wealth and military might undergird a country’s prosperity in an anarchical world. In his presidential debates and subsequent statements, he has interpreted Indonesia’s long-standing foreign policy motto bebas aktif, or “free and independent” in Bahasa Indonesia, to mean that Indonesia will be a “good neighbour” – continuing the “many friends, zero enemies” posture of the two presidents before him. He is also a pragmatist: Prabowo’s foreign trips reflect his willingness to meet diverse partners in Asia and Europe to shore up Indonesia’s positions in trade, defence, security and other areas, although some predict possible tensions given his past rhetoric against issues like the EU’s sanctions on palm oil.

As defence minister, Prabowo strengthened Indonesia’s defence diplomacy by signing various pacts with partners like Singapore and Australia to improve and support the Indonesian military (TNI). Some criticised his approach as scattershot and transactional, and the TNI has not reached its “minimum essential force” goal, but Prabowo had inherited a dismal situation created by decades of underinvestment. As president, Prabowo will continue to emphasise defence cooperation, including with smaller neighbours like Brunei and by giving arms and aid to Cambodia, while privileging defence relationships with bigger powers. He might also try to level up Indonesia’s defence industry, which faced various challenges under Widodo.