The Singapore-China ties Lawrence Wong inherits from Lee Hsien Loong

- Under Lee, bilateral ties were upgraded through economic initiatives and dialogue platforms – despite occasional political hiccups

- Lee also highlighted multiculturalism in diplomatic exchanges and took pains to ensure Singapore was not ‘a cat’s paw’ for any other country

The fact that bilateral ties have largely been stable is credit to a historically strong partnership and the Singapore government’s steady stewardship of that relationship.

Major Singapore-China platforms were initiated and strengthened under Lee. The Joint Council for Bilateral Cooperation, established in 2003, provides an equal and high-level arena for regular dialogue. Indeed, the first joint council in May 2004 was co-chaired by Lee while he was still deputy prime minister. The somewhat lesser-known Singapore-China Forum on Leadership, first held in 2009, and Singapore-China Social Governance Forum, which began in 2012, were also launched under Lee’s watch.

Small hiccups, growing ties

Still, the relationship has not been completely smooth sailing.

Despite these issues, Lee has heralded a closer relationship with China, particularly on the economic and political fronts. It was under Lee’s leadership that Singapore in 2013 became the largest foreign direct investor in China, while China became Singapore’s largest trading partner. During Lee’s tenure, the total number of bilateral flagship projects rose to three, with the Tianjin Eco-city in 2008 and 2015’s Chongqing Connectivity Initiative joining the Suzhou Industrial Park (1994).

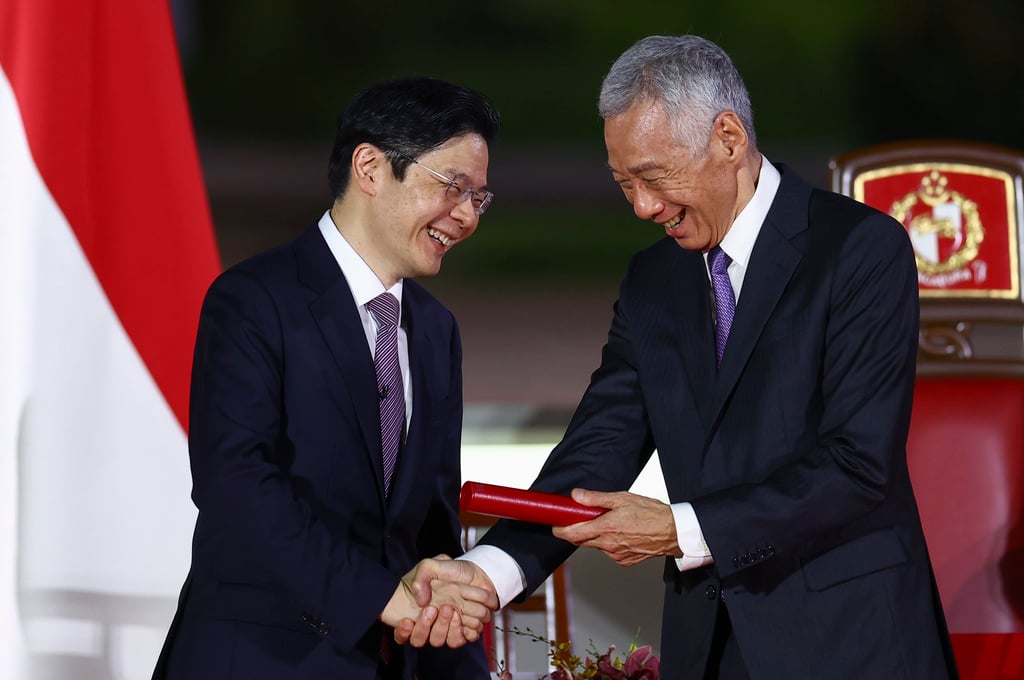

Bilateral relations were also upgraded to an “all round high-quality future-oriented partnership” in April last year.

Singapore has largely managed to chart its own course and continues to have meaningful and substantive areas of cooperation with both. While Singapore’s influence should not be overstated, it is quite remarkable that such a small city state can credibly hold its weight and find its voice in the Chinese and American corridors of power. In fact, Xi said in 2023 that Singapore-China ties set the benchmark and served as a “model” for other countries. It is also no accident that the summit in 2015 between Xi and Taiwan’s Ma Ying-jeou took place in Singapore, reflecting the considerable political trust and goodwill it has painstakingly built up.

Distinctly Singaporean

Barring the pandemic years, Singapore has undergone a deliberate and intense level of political engagement with Beijing. Lee’s state visit in March last year was the most recent example, with Singapore’s 4G leadership also being inducted with frequent high-level visits. These often involved non-Chinese politicians to visibly underline the city state’s multi-ethnic make-up. In that way, under Lee, there have been greater efforts to highlight multiculturalism in the face of Beijing’s increased attempts to claim proprietorship over peoples of Chinese ethnicity.

In 2012, Lee supported the construction of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre. It is hard to miss how it serves as a counterpoint to the China Cultural Centre established by Beijing. In his 2022 National Day Rally, Lee also underscored the unique Singaporean Chinese practices that had emerged and, importantly, noted that “Chinese Singaporeans had sunk their roots here in Singapore” and were distinctly Singaporean.

Informed by an acute sensitivity to the city state’s multi-ethnic and multicultural make-up, significant work has been invested into letting others – and Singaporeans – know that the republic is not, in the words of Lee, “a cat’s paw” for any other country and no one should conflate cultural affinity to China with political loyalty to China.

In sum, these moves portend a broader shift to improve foreign policy literacy that will hopefully remain a priority item under the new prime minister.

Lee the statesman

It is quite telling that Lee’s critics have largely focused on domestic policies rather than any major foreign policy issues – a testament to how well Singapore has managed its external affairs, thus far.

Lee’s acumen in international affairs and ability to grasp the complex issues of the day with a helicopter view is probably peerless in Singapore. His Foreign Affairs essay on “The Endangered Asian Century” in June 2020 foreshadowed much of the current dynamics of US-China competition and existential angst about the international order that many Southeast Asian countries feel today.

But Lee also used an “ant’s eye view” to adeptly translate these global issues for the man on the street, carefully explaining what US-China competition and the war in Ukraine meant for Singapore and Singaporeans during a parliamentary debate last year.

As with any relationship, there will be challenges in Singapore-China ties. As Lee suggested, the city state’s new leadership “may be probed” by major powers, including China. Other risks may include slower-than-expected economic growth in mainland China, flashpoints in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea, renewed endeavours to influence society, or a sharp deterioration in US-China ties – all of which will test Wong’s foreign-policy mettle. At the same time, new opportunities will present themselves, and it is incumbent upon the prime minister and his team to seize these in service of Singapore-China relations.

As Wong alluded to in his speech, old formulas and dicta may not suffice in today’s more complex international environment. Is it enough, or desirable, to simply “keep the ship steady” or maintain the status quo? Can there be greater public discourse on big foreign-policy questions? Is there scope for fresh thinking about Singapore’s place in the world, while being clear-eyed about the limits of what it can do?

There are no obvious answers, but what is clear enough is that Lee has handed over the “China account” in very good shape, with the potential to do much more.

Dylan M.H Loh is an Assistant Professor in the Public Policy and Global Affairs Programme at Nanyang Technological University. His latest book, China’s Rising Foreign Ministry, examines Chinese diplomatic practices in Southeast Asia.