Advertisement

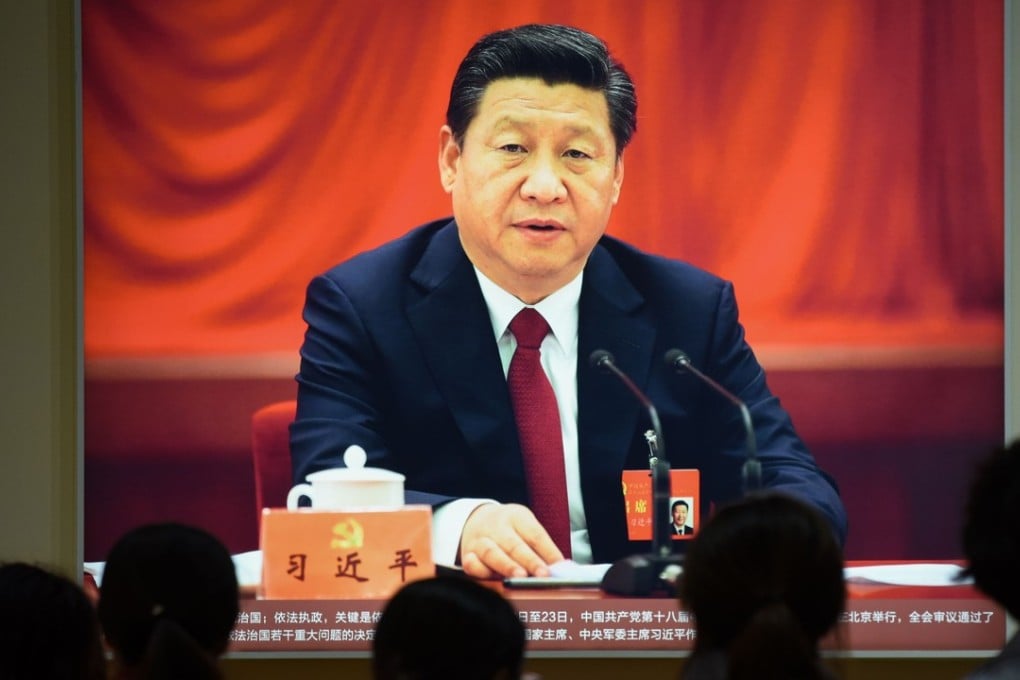

On Reflection | A global China must ask itself awkward questions. Is it ready?

China seeks to lead the modern world. Yet its reaction to scholar Xu Zhangrun’s veiled criticism of Xi Jinping suggests its attitude to intellectuals is stuck in the past

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

An essay by Tsinghua University professor Xu Zhangrun, a veiled criticism of Chinese President Xi Jinping, has resonated across the internet since its appearance late last month. The essay, which has been repeatedly wiped off the Chinese internet, voices a profound unease about the direction of Chinese politics. Talking to Chinese writers and academics in the past year, I’ve also been struck by their sense of uncertainty. Historical topics that were fine to write about just a few years ago can’t now be published. Contemporary political issues, such as potential flaws in the Belt and Road project, aren’t being debated in the media, even if they are the subject of furious discussion offline.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Xu’s essay is an example of a historical phenomenon that has occurred repeatedly in Chinese history, particularly in the modern era: the warning from an intellectual to the leader that the country may be on the wrong path.

Some of the most intellectually productive eras in modern Chinese history have been times of political weakness. The “new culture” period around the May Fourth demonstrations of 1919 was one such, sitting in the middle of the “warlord” era of Chinese politics. Much of the second world war saw a huge amount of political debate and pluralism. A third such period took place in the 1980s, at the end of the Cultural Revolution.

Is Xi losing his grip – or taking a more flexible approach?

China’s vulnerability provided a reason for thinkers to feel urgency about new solutions, but also left gaps in the public sphere that allowed criticism to emerge clearly. In contrast, strong leadership has often meant new thinking is stifled.

Advertisement

Advertisement