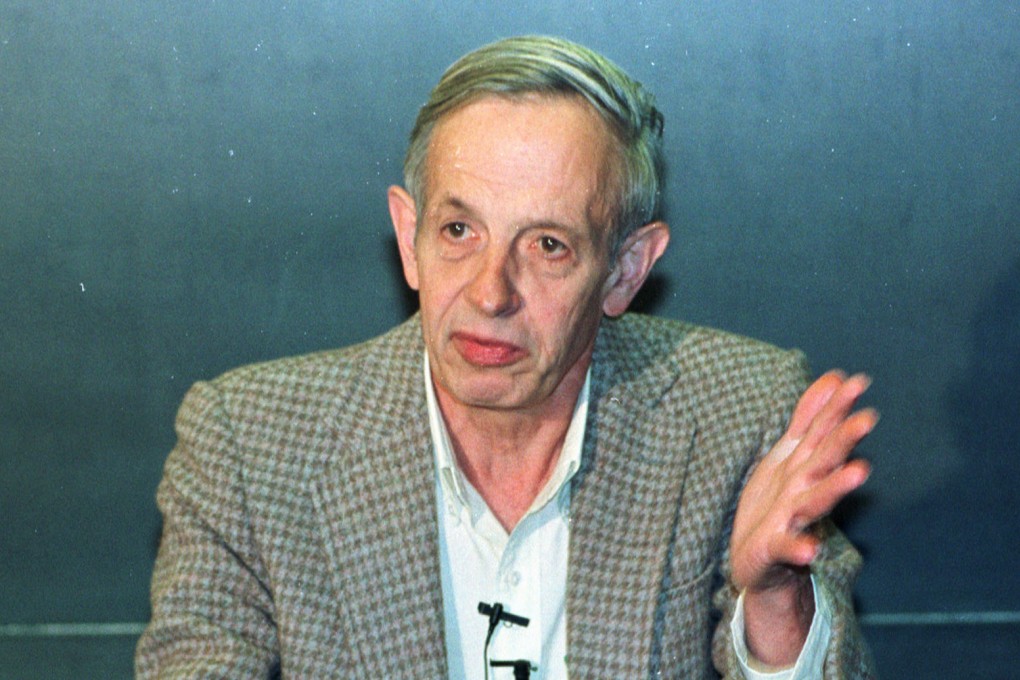

John Nash's 'beautiful mind' opened whole new vista for mathematics

Many mathematicians, including fellow Nobel laureates, have delved further into the game theory he pioneered at the age of only 22

When I read the tragic news of John Nash's death at age 86 in a car crash last week, my first thought was not of his Nobel Prize in economics, nor of his redemptive life story dramatised in the film A Beautiful Mind. The memory that came to mind was of a summer night in 2002 and an event in the faculty club at Princeton University.

The room was abuzz with anticipation: Nash was guest of honour and scheduled to make some remarks - rare for the eccentric mathematician.

A hush fell. My host whispered: "Nash is here." I saw a tall, stooping, white-haired figure enter the room and shake a few hands. Then he turned around and left without a word.

But that was part of his lingering legend as "the phantom of Fine Hall". He was often spotted wandering the corridors of Fine Hall, where Princeton's mathematics department is located, during his decades of mental illness. By the time I saw him he had recovered from his illness, received the 1994 Nobel Prize, and lived as normal a life in Princeton as fame from the 2001 Oscar-winning film allowed.

It was at Princeton in 1950 that Nash submitted a 27-page, double-spaced doctoral dissertation that pioneered modern game theory and its application to economics. He was 22 years old, only two years into his PhD programme.

At the time, Princeton was the centre of the mathematics universe: Albert Einstein, the polymath John von Neumann, the logician Kurt Gödel and other intellectual titans were working there. Yet Nash developed his theory alone.