Hong Kong’s darkest December brought a season without peace or goodwill

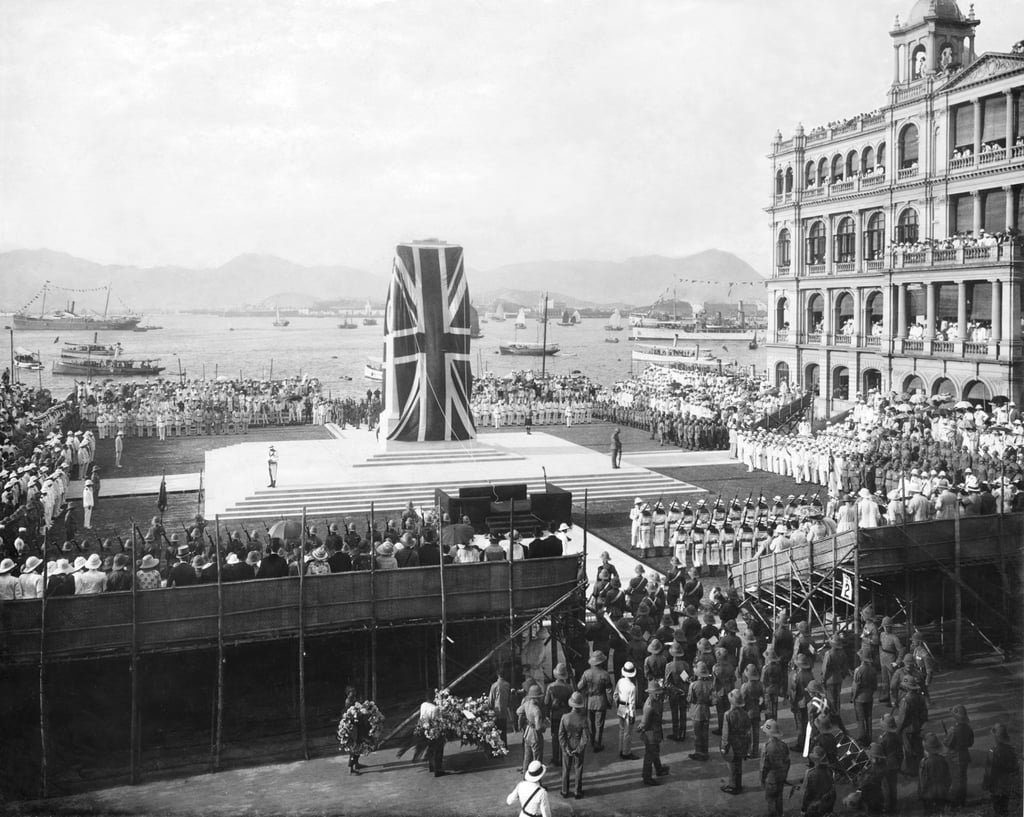

Hong Kong’s array of wartime memorials means the city will never forget those lost in the traumatic aftermath of December 1941 and the surrender on Christmas Day

During the weeks before Christmas, Hong Kong becomes hectic with seasonal shopping, bright decorations and strings of parties, which culminate in eagerly anticipated gatherings on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Religious services, family gatherings, traditional meals drawn from a variety of cultural backgrounds, and a secular public holiday merrily enjoyed by followers of any creed or none – all epitomise the festive period here.

But for many families, that day also represents experiences of destruction, grief and loss. On Christmas Day 1941, Hong Kong was surrendered to the invading Japanese, after 18 days of pitched battles fought across the territory. During the decades that followed, war’s lasting shadow, along with bitter memories of nearly four years of enemy occupation, loomed large. For those who had lived through those events of 1941, December became a roll-call of sombre private anniversaries; for a brother killed, husband taken prisoner, or father wounded. Dates to always remember – or somehow, try to forget.

Eighty-three years later, memories of the conflict have faded. Anyone living here today, who can accurately recall where they were and what they were doing on the day Hong Kong fell, are now at least in their late 80s. All adult survivors of that “Captive Christmas” have now passed away. When peace returned to Hong Kong, in August 1945, too many lives were never the same. Wartime trauma’s unseen scars lingered for another lifetime, and never truly faded away.

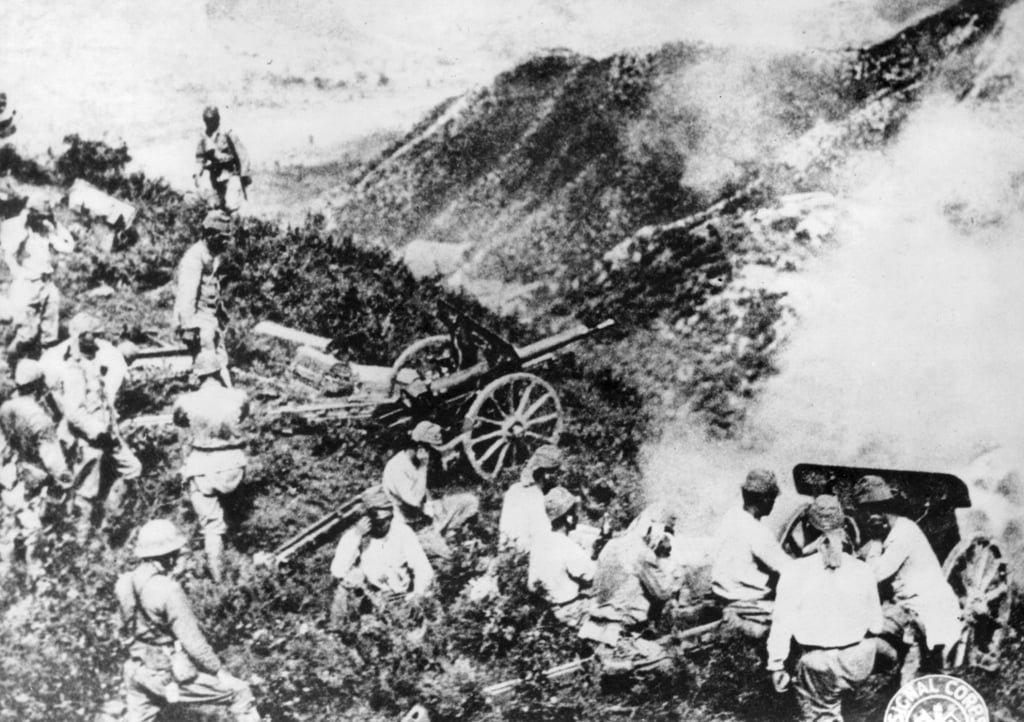

An extensive built legacy of pre-war defence structures remains, perched high upon mountain ridges and coastal cliffs, or tucked away behind modern buildings deep within the city’s urban fabric. Some locations – such as Wong Nai Chung Gap and Jardine’s Lookout, which straddles Hong Kong Island’s strategically vital geographical middle – briefly became savagely fought-over battlefields. Other heavily fortified artillery positions, such as those around Mount Davis, were barely used. At Cape D’Aguilar, Chung Hom Kok, Stanley and elsewhere around Hong Kong Island, ruined gun batteries and machine-gun posts still glower out to sea through the heavy undergrowth that, several decades later, has surrounded them.

When the abandoned hillside tunnels and bunkers that overlook the Shing Mun Reservoir, above Tsuen Wan, are encountered on a countryside hike, those desperate events from long-ago days suddenly loom, close-up and immediate, and the past cannot be easily ignored. At such startling moments, these desolate places offer a quiet opportunity to pause and reflect upon life today – especially if chanced upon during a peaceful Christmas Day tramp in the winter sunshine.