Advertisement

Macroscope | As US dollar dominance persists, what if the centre cannot hold?

- No state can withdraw from globalisation on its own terms, and the world cannot have one power in effect running monetary policy on behalf of everyone else

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

11

The US economy has got stuck. It is stuck with a relatively high inflation rate because of strong domestic consumption and employment, and it is stuck with high interest rates as a result. This in turn means it is stuck with a strong dollar, which then drags on US competitiveness.

Advertisement

In turn yet again, this encourages tariffs and other forms of protectionism which, when combined with geostrategic competition, mean the world’s largest economy is stuck with the label of being a trade and investment spoiler. And that is not the end of the story.

The United States is stuck too with strong capital inflows, attracted by the strong dollar like a moth to a flame. These push up the dollar even further and encourage the kind of foreign borrowing and growing national indebtedness that are beginning to worry US bond markets.

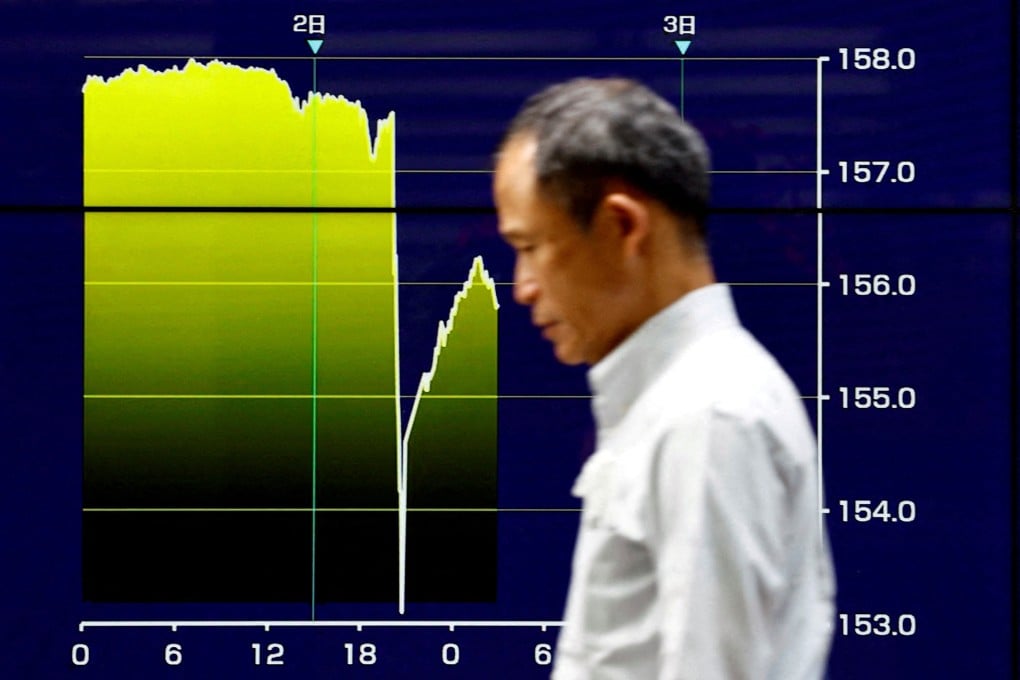

Where will this vicious circle end? Maybe in currency crises if major US trading partners such as Japan continue to spend their official reserves on trying to restrain their currencies from falling so far against the dollar as to threaten the danger of imported inflation.

Japan has spent a record near ¥10 trillion (US$64.15 billion) over the past month from its foreign exchange reserves on market interventions to prevent the dollar exchange rate from blasting above 160 yen, according to recent finance ministry data. Japan has sufficient reserves to be able to withstand this, but that is not the case with many other Asian nations that have seen the dollar soar higher against their currencies.

Advertisement

This could end in tears if the dollar remains in free flight or, contrariwise, if the US is forced to drop its interest rates – possibly quite sharply – to keep the “Make America great again” show going in the run up to the US presidential election in November. That could precipitate currency market turmoil or even a crisis.

Advertisement