Why Western hype about Hong Kong losing its high degree of autonomy rings hollow

- A report on Hong Kong by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies does not appreciate fundamental pillars set out in the Basic Law

- The city is still governed by Hongkongers, maintains judicial independence and has an international identity under the umbrella of China

It reaches the same conclusion as other such studies and reports issued by US and UK think tanks in recent years: the Chinese government has “significantly eroded Hong Kong’s ‘high degree of autonomy’”. While it contains less over-the-top political rhetoric than the others, it nevertheless exhibits the same lack of appreciation of the issues at heart, which makes it a truly disappointing read.

Measuring Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy without understanding its limits is tantamount to commenting on the US constitution, without reference to the amendments, particularly the first amendment.

If, for the sake of argument, the rights of Hongkongers had been somewhat restricted by the national security laws, such limitations would be in line with both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Basic Law. Thus, one cannot call it an erosion. If there has never been a right to violate national security, it follows that there can never be an erosion of such a right.

Under the Basic Law, our high degree of autonomy is premised on certain essential pillars: Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong, judicial independence and the maintenance of our international identity under the umbrella of China.

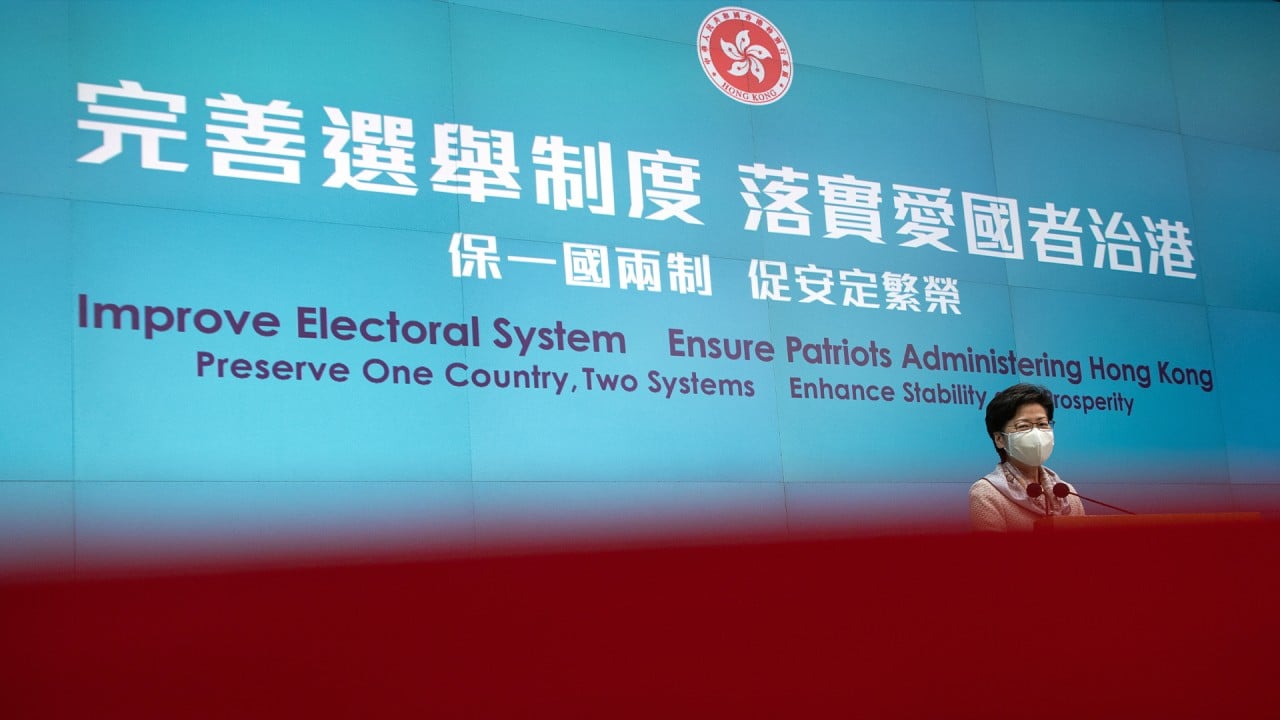

The Joint Declaration made no mention of political reform. In fact it is the Basic Law, enacted by the central government, which promised universal suffrage to the people of Hong Kong. Back in 2014, the central government even proposed a political reform package aimed at electing the chief executive by universal suffrage, but it was voted down by the pan-democratic camp in the Legislative Council.

That was extremely shortsighted and unfortunate. Without pointing fingers, I would like to stress that this was a case of reform failure, not an erosion of rights. One can only hope that with the issue of national security resolved once and for all, and as Hong Kong’s stability and harmony is restored, we can move forward again on political reform.

As for judicial independence, the only thing to say is that it is alive and kicking. The CSIS report could not cite a single example to support its conclusion that this important pillar has been eroded aside from bringing up our judicial independence through a national security lens.

It is important to note that both the national security law enacted by the National People’s Congress and Article 23 legislation passed by the Legislative Council emphasise that the rule of law applies to national security offences.

Foreign judges continue to sit on our courts and English continues to be used in court proceedings. Our trials are open, evidence is presented openly and judgments are published for all to see.

The CSIS report does not specifically touch on Hong Kong’s independent international identity under the designation of China. The truth is that we continue to present a distinct voice as an international centre of finance and commerce on the world stage.

It is superficial to just look at trade figures without examining Hong Kong’s independent identity in various international institutions and forums. The latter has not changed and continues to shine and move forward.

The report has at least one partially redeeming feature – its proposal that the US should adopt a “strategic engagement” approach by “solidifying practical interactions between state and non-state actors in the United States and Hong Kong”.

However, even this proposal is marred by the qualification that such interactions should be backed by “punitive measures”. This, sadly, is a contradiction, as if coercion based on political bias is a fair and reasonable premise for any engagement.

Ronny Tong, KC, SC, JP, is a former chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association, a member of the Executive Council and convenor of the Path of Democracy