Advertisement

Opinion | Why China’s gains from multipolarity have yet to outpace US dominance

- Countries in the Global South are aligning with Chinese commerce when it suits them, but still choosing to protect domestic industries

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

11

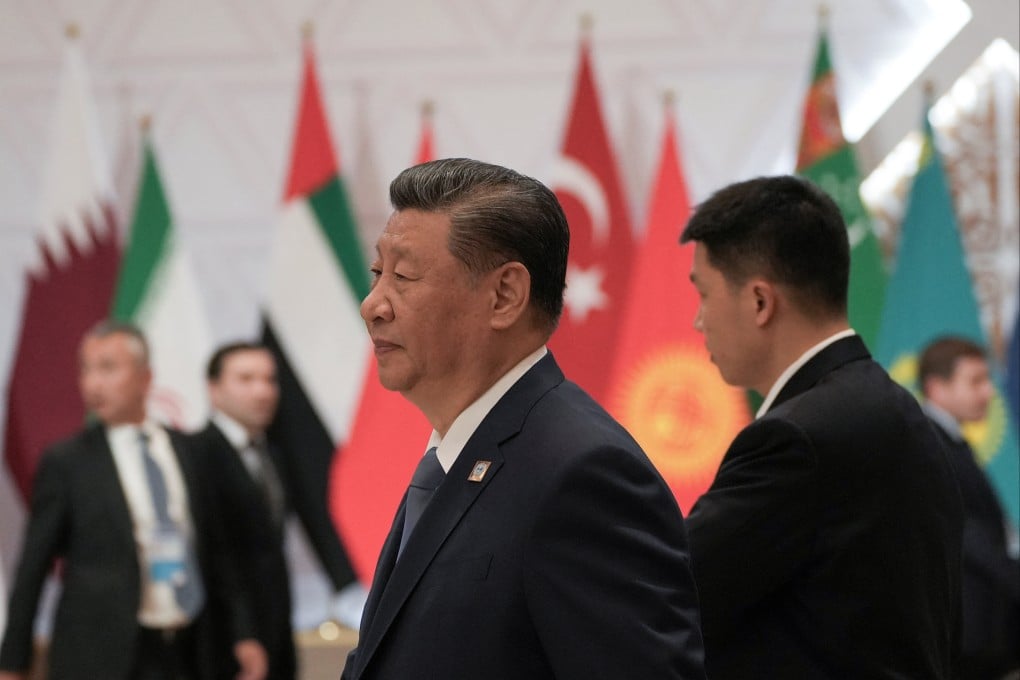

At the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Astana, Kazakhstan, on July 4, Chinese President Xi Jinping emphasised that “the international landscape is undergoing rapid transformation”, a euphemistic way of saying that the post-Cold War international order dominated by the United States is coming to an end, to be replaced by “an equal and orderly multipolar world”.

De-dollarisation of the global economy has been cited by some as one of the main changes in international power play as China continues its rise at the expense of the US’ decades-long leadership. But dollar dominance in reserves, trade and transactions is still rock-solid, as signalled by the Atlantic Council’s Dollar Dominance Monitor.

The current geopolitical trend is actually a different one that goes against the narrative of US decline. If the international system is experiencing a rapid transformation, this is because “de-Sinicisation” of world trade is accelerating.

The European Union’s recent decision to impose provisional extra tariffs on Chinese-made electric vehicles – pending an anti-subsidy investigation that the EU Commission is due to conclude in November – is part of a series of protective measures adopted by countries or entities challenging what they say are Beijing’s market distortions.

The list is lengthening. In May, the United States announced new tariffs on US$18 billion worth of Chinese imports, including a 100 per cent duty on the import of Chinese-manufactured electric vehicles. Turkey and Brazil have their own trade barriers to Chinese electric cars. India says its car market is “well-protected” by high tariffs on the import of electric vehicles, and Canada is considering imposing penalties similar to those of the EU.

Chinese trade practices are also in the crosshairs of countries in Southeast Asia. Thailand is mulling anti-dumping actions against a host of Chinese goods, and Indonesia is preparing to do the same for textiles.

Advertisement