My Take | Western ‘lawfare’ forces Hong Kong’s foreign judges to quit

- The city must be grateful for the expertise and service these members of the judiciary have provided, but they have served their historic purpose

Lawfare, according to the Oxford dictionary, is a neologism that means legal action undertaken as part of a hostile campaign against a country or group. It’s obviously a play on the word warfare. Another way of understanding is to politicise the law, whether your own or that of another state, to attack your enemies, who could be domestic or foreign.

For years, a united front of politicians and pundits from Britain, Canada and Australia have been demanding the resignation of non-permanent judges from their countries serving in Hong Kong’s top court. The United States – which has no such judges here – has gone further: a powerful bipartisan group of lawmakers have been demanding sanctions against some of the city’s senior judicial and police officers.

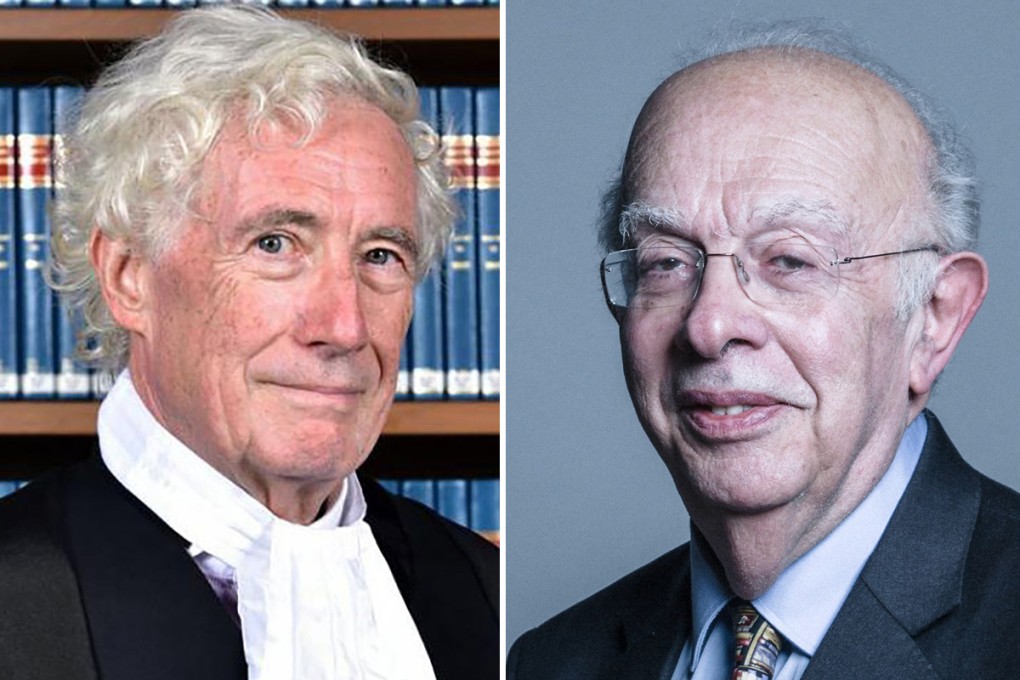

This highly coordinated Anglo-American lawfare has been pretty successful. Its latest score has been the resignation of Lawrence Collins and Jonathan Sumption, two British non-permanent judges appointed to the Court of Final Appeal.

While their resignations have been described as a “shock”, it’s really a matter of time given the intense pressure that has been exerted on the judges to quit from the UK government, media and professional legal bodies.

Collins told this newspaper he resigned “because of the political situation in Hong Kong”, but said he still had the “fullest confidence” in the court and its total independence. If so, why quit?

The pair’s resignations followed those of Robert Reed and Patrick Hodge, two British Supreme Court judges, in 2022. Ex-Canadian Supreme Court chief justice Beverley McLachlin, who is facing similar pressure from her country, may be next.

Three Australian judges and David Neuberger from Britain have declared they will stay. All those judges, past and present, have served Hong Kong well. We should be grateful for their expertise, prestige and integrity.