Simulated global pandemic leaves 150 million dead. A real one could be much worse

Exercise simulated a global health disaster with fictional elements to force government officials and experts to make the kinds of key decisions they could face in a real pandemic

A novel virus, moderately contagious and moderately lethal, has surfaced and is spreading rapidly around the globe. Outbreaks first appear in Frankfurt, Germany and Caracas, Venezuela. The virus is transmitted person-to-person, primarily by coughing. There are no effective antivirals or vaccines. American troops stationed abroad are infected. Now the first case to reach the United States has been identified on a small college campus in Massachusetts.

So began a recent day-long exercise hosted by the Johns Hopkins Centre for Health Security. The simulation mixed details of past disasters with fictional elements to force government officials and experts to make the kinds of key decisions they could face in a real pandemic.

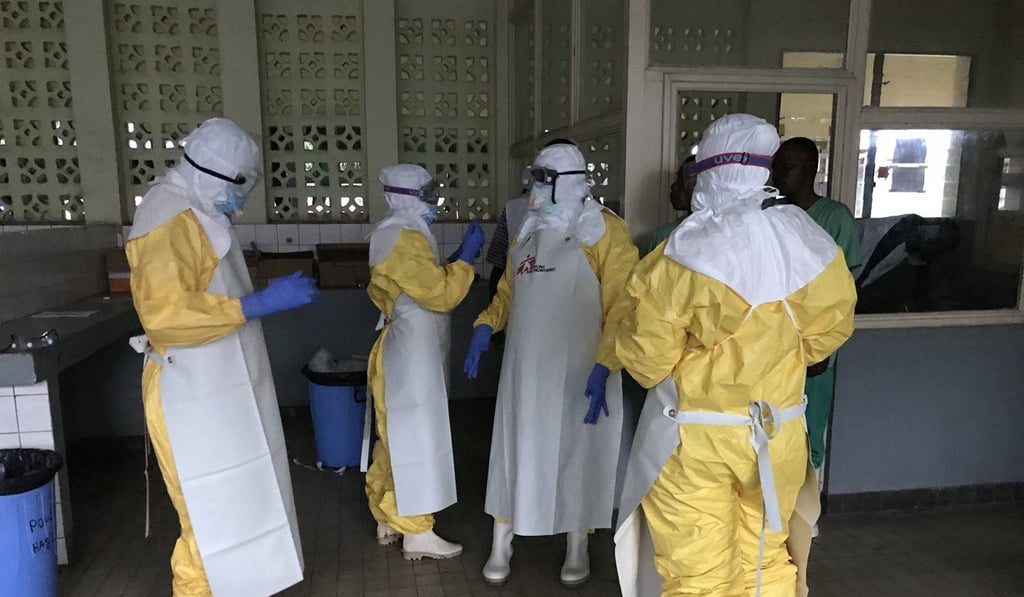

It was a tense day. The exercise was inspired in part by the troubled response to the Ebola epidemic of 2014, and everyone involved was acutely aware of the very real and ongoing Ebola outbreak spreading in Congo.

In the simulation, a bipartisan group of current and former high-ranking US government officials played a team of presidential advisers faced with a host of real-world policy, political and ethical dilemmas.

The actors included former Senate majority leader Tom Daschle, who played the Senate majority leader, and Representative Susan Brooks, who played herself.

They had to react as the outbreak unfolded according to a script provided by Johns Hopkins, with no advance knowledge about how the mock disaster would play out.