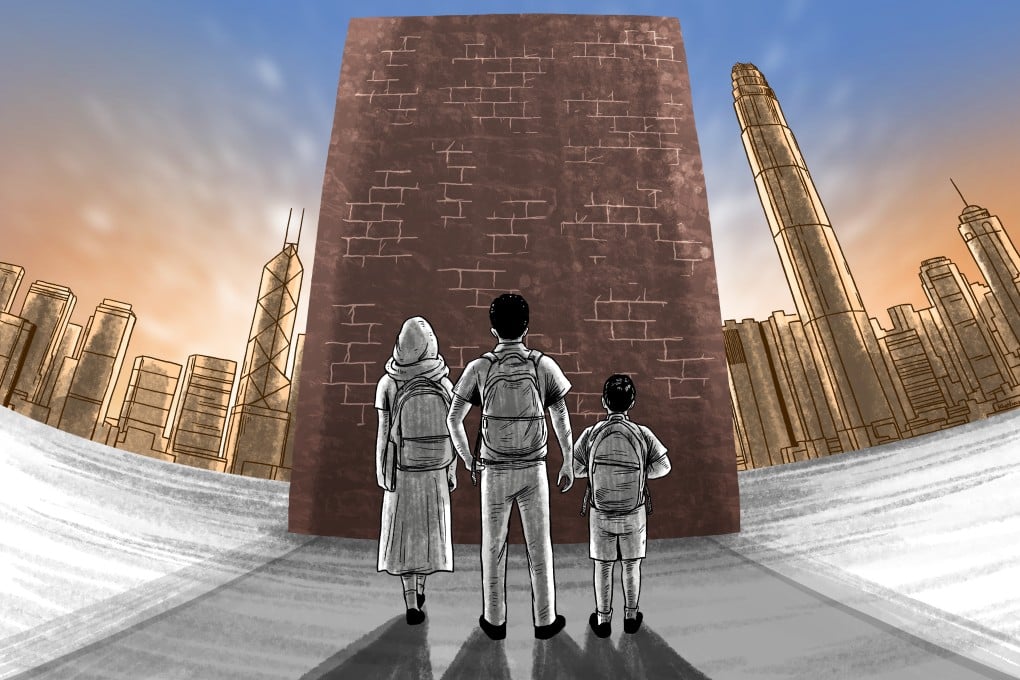

‘Give me the opportunity’: have Hong Kong’s society and schools failed ethnic minority students?

- Societal norms and trends in early education have concentrated non-Chinese-speaking students in certain kindergartens or primary schools

- Weak Chinese-language standards mean such pupils rarely have motivation to learn, especially if they remain in comfort zones and rarely interact with peers

Kraiz Kayastha has had a difficult six years of primary school. The 12-year-old is enrolled at a local school in Hong Kong where his lessons are taught in Chinese.

In Primary One, Kraiz, who was born in Hong Kong with Nepali roots, had little to no command of the Chinese language. Now in Primary Six, Kraiz struggles through two sentences of a self-introduction in Cantonese before switching back to English.

He is among the 33,000 non-Chinese-speaking – classified by the government as NCS – children studying at schools in Hong Kong, where their grasp of the language has been a long-standing struggle.

Critics argue that preferences by parents and schools have created a form of “de facto segregation”, in which certain campuses in the city, especially those designated for NCS students two decades ago under a now-scrapped government policy, still take in a disproportionate number of such pupils.

The trend perpetuates a cycle where ethnic minority youth get stuck in lower-banded schools and rarely break out of the predetermined education path set for them.

Kraiz’s mother Chandra Gurung was also born in Hong Kong, but grew up and studied in Nepal. She had dreams of a stable career, working nine to five at an office or a bank. But reality struck when she returned to Hong Kong as an adult. Gurung said she worked long hours in jobs she did not want, such as waitressing.

“I have been a housewife for a long time,” she said. “I got rejected from so many [jobs], only because I’m not proficient in Cantonese.”

Now a mother of three sons, she has begun to worry that her boys would suffer the same fate.