China’s extradition requests must be based in law, not on persuasion

- Beijing’s pursuit of fugitives overseas is rooted in President Xi Jinping’s call to end ‘avoidance paradise’, but bringing them home is not straightforward

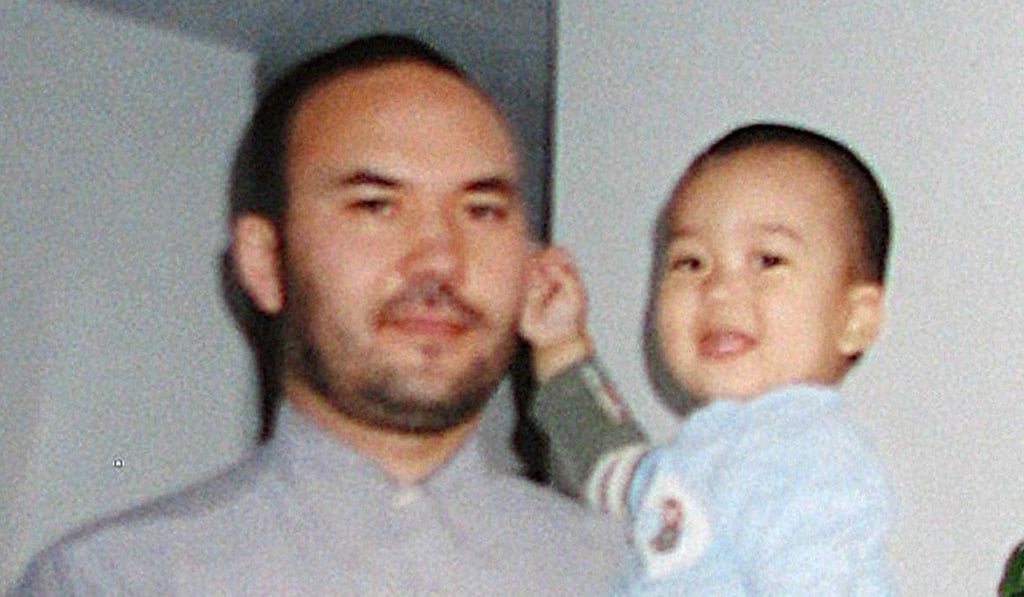

In March 2006, Huseyin Celil, a Canadian citizen who was visiting Uzbekistan, was arrested by Uzbek police. The Canadian government requested Celil’s release and return to Canada, but the Uzbek government deported him to China. In November 2006, he was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment for terrorism.

The case did not attract a great deal of attention outside Canada, perhaps because Celil was born in China, and China claimed, unconvincingly, that he was a Chinese citizen. It served as an example of what may be a growing trend: the extradition of non-Chinese citizens to China.

China’s aggressive pursuit of fugitives overseas goes back to early 2014, when President Xi Jinping said: “You can’t let foreign countries become the ‘avoidance paradise’ for corrupt elements.”

Communist Party Central then set up the Central Pursuit Office, which is supported by staff from several ministries, including the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the police, the Ministry of State Security, and the People’s Bank of China.

The office gave catchy names to its operations, such as “Fox Hunt” and “Sky Net”. It stated that it used four methods to get hold of suspects overseas: extradition, the forced repatriation of illegal immigrants, overseas litigation, and “persuasion”.

Extradition is the gold standard, from China’s point of view. China initially was able to sign extradition treaties only with less developed countries such as Uzbekistan, but as its status improved, so did the number of treaties, and recently it has concluded treaties with Italy, France and Spain.