How passion and tech resurrected China’s headless statues, and unearthed historic wrongs

‘Monuments woman’ Katherine Tsiang’s Buddhist statue digital restorations have revived interest in lost dynasties and protection of cultural treasures

A groundbreaking project led by the Chinese-American art researcher involves the sixth-century Buddhist cave temples at remote Xiangtangshan, or Mountain of Echoing Halls, in China’s northern Hebei province.

The caves –which are shrines carved from limestone cliffs – were extensively damaged by looters during political upheaval in China around the turn of the century, with smaller statues stolen and large Buddha heads or hands chiselled off, to be sold on the international art market. It is believed that more than 100 such pieces are now scattered around the world.

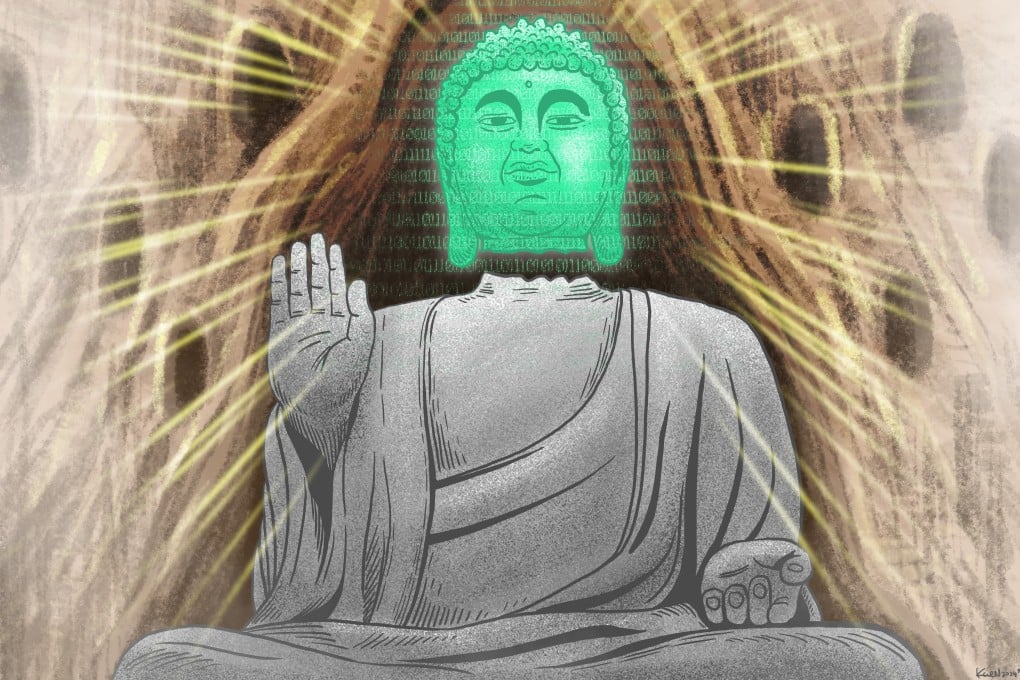

Tsiang’s team has tracked and scanned the dispersed fragments of sculpture and the original sites using advanced 2D and 3D imaging technologies to produce digital reconstructions of the caves that date to the short-lived Northern Qi dynasty (AD550-577). In 2019, digitally printed missing pieces from six Buddhas were displayed in a museum in Xiangtangshan, with more exhibitions expected.

“You cannot glue a 600 pound (272kg) sculpture back on the wall of the cave, but with the digital information, you can create a virtual reconstruction of a cave, even print it out and make it into an actual space that people can visit,” said Tsiang, who now works as a consultant for the Centre for the Art of East Asia at the University of Chicago after retiring as its associate director earlier this year.

Tsiang joined the renowned academic centre in 1996 after a stint teaching Chinese, Indian and Japanese art history at the Herron School of Art and Design at Indiana University Indianapolis. She studied Buddhist art with a focus on the Xiangtangshan caves for her PhD and has since built a career as a “monuments woman” – a term first coined to describe people dedicated to the protection of cultural treasures during and after World War II.