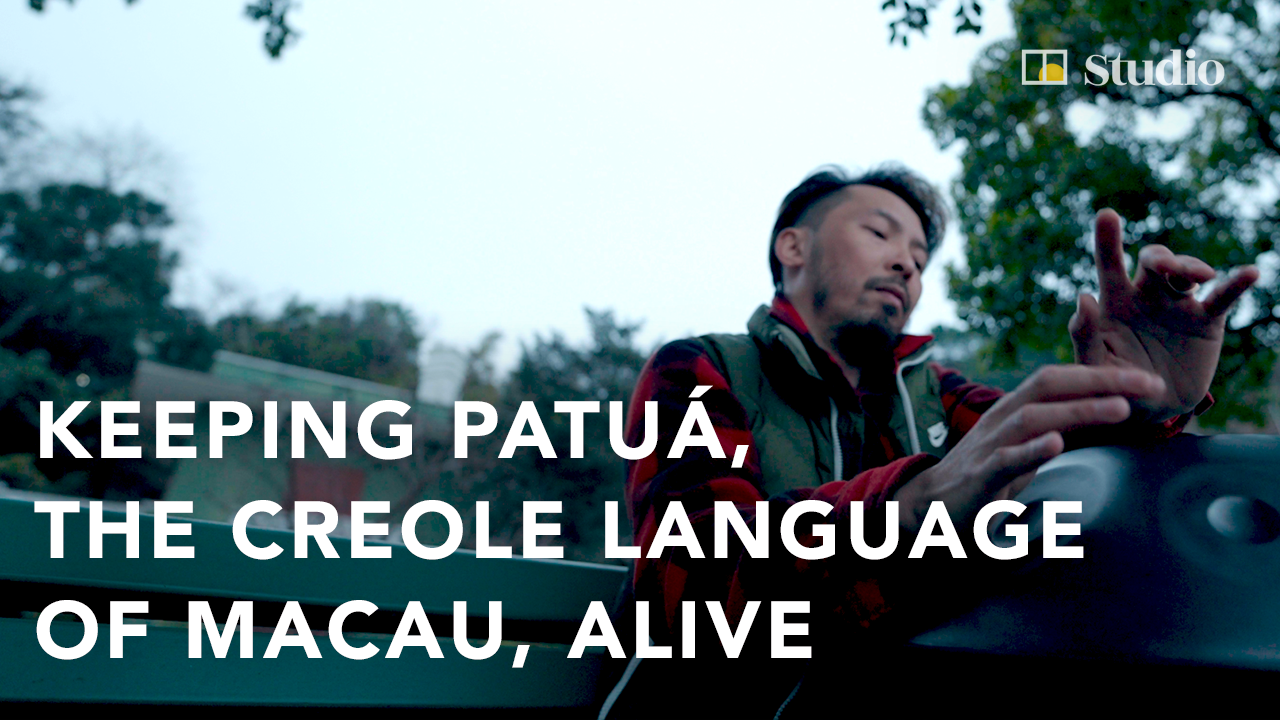

How Patuá, the ‘critically endangered’ creole language of Macau, is being rescued by a younger generation

- The home-grown language, which combines Portuguese, Cantonese and words from other Asian languages, is estimated to have only 50 fluent speakers left

- Two locals of Macanese heritage – a scholar and a musician – are raising awareness of Patuá by incorporating it into creative works

Walking the streets of Macau, one is constantly reminded of the city’s history as a Portuguese trading outpost, from the southern European architecture to the bilingual street signs. Macanese cuisine, a blend of Portuguese and Asian cooking widely known as the original fusion food, is also part of that legacy.

Far less known to the outside world, however, is Patuá, a creole language developed within the Macanese community of mixed Portuguese-Chinese people. Dating back to the 16th century, Patuá is primarily based on Portuguese but also borrows from Cantonese as well as Japanese, Timorese, Malay, Konkani (the language of Goa, India), Hindi, Dutch and English.

Today, Patuá is classified as “critically endangered” by Unesco, with only an estimated 50 fluent speakers remaining. But a movement is under way to preserve the language, started by a younger generation of Macanese who recognise the value of their unique heritage.

They include Elisabela Larrea, an eighth-generation Macanese and scholar who has devoted her work to preserving Patuá through various mediums, including theatre.

“As far back as the 1930s, many parents [in Macau] would disallow their children from speaking Patuá as they wanted the next generation to speak standard Portuguese, which they believed would help secure better jobs and futures,” she says.

“But in recent years, views have changed, and they realise that creole languages reflect history and the lives of people in different cultures. Many are now retrieving the language and relearning it. Compared to 20 years ago, there are more people speaking it.”

Larrea did not grow up speaking Patuá, but when her mother took her to a play written in the language, she immediately connected with that piece of her heritage. “It just felt like home,” she recalls of that introduction 24 years ago. “There were words that I did not know, but I was surprised that I understood what they were saying, and people in the audience were laughing and having fun.”