How the Scottish influenced Hong Kong’s New Year’s Eve celebrations

Hong Kong has close ties to Scotland including its own Aberdeen, streets named after Scottish colonials and hiking trails named after governors

Compared to Lunar New Year, Western New Year’s Eve can seem a rather lacklustre affair. While it’s probably the most widely celebrated occasion in the modern world, an impartial observer might not be able to pin any unique attributes to the holiday. It is neither a religious festival nor a distinct cultural tradition. It doesn’t have dragons or brightly coloured lions, nor does it have a huge bearded man in a red suit, still less, a baby in a manger.

Perhaps that’s why, for their New Year’s inspiration, English-speaking nations all the way from North America to Britain to Australia and New Zealand look to the Scottish tradition of Hogmanay. Because when it comes to New Year’s Eve, the Scots display a creativity and joie de vivre that can go toe to toe with the most colourful festivals in the world.

And let’s not forget, Hong Kong has close ties to Scotland: the city has its own Aberdeen and a profusion of streets and landmarks: consider Lockhart Road, named after Colonial Secretary James Haldane Stewart Lockhart, or the MacLehose Trail, named after former Governor Murray MacLehose. So there’s more than enough excuses to do New Year’s the Scottish way.

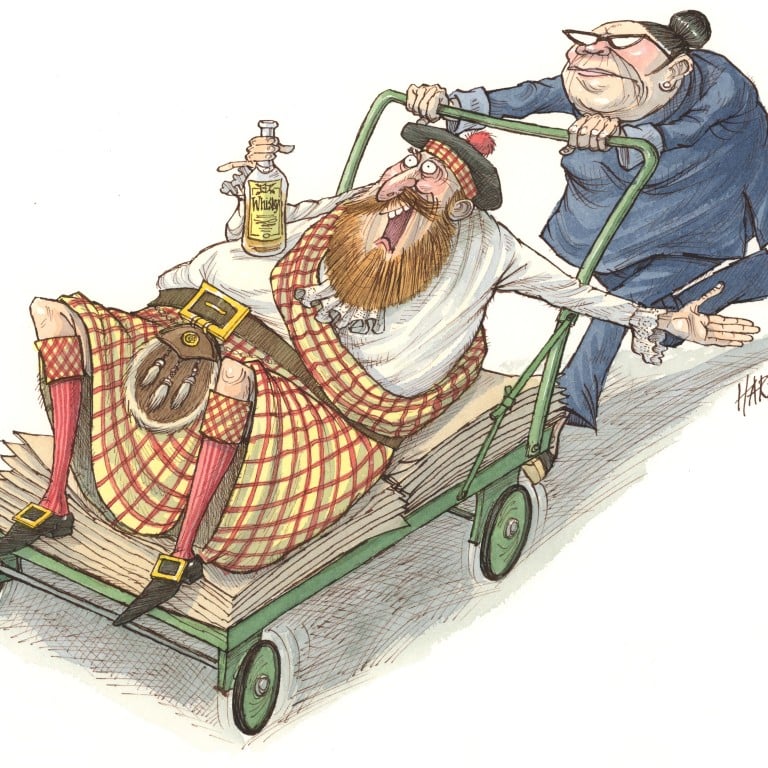

There are hot debates about where the name Hogmanay comes from, but everyone agrees it denotes the end of the year and generally lasts three days. In Scotland, Hogmanay is a regional affair, with different areas celebrating it in different ways. But most involve a great deal of singing, dancing and drinking copious quantities of malt whisky.

Some regional traditions are somewhat hair-raising, and under no circumstances should be attempted elsewhere. At the stroke of midnight in the town of Stonehaven, in Aberdeenshire, for example, large, heavy balls of wire are filled with flammable materials and set alight. These are then twirled, blazing, over the heads of marchers who walk through the town centre. This celebration is known as the Fireballs Ceremony.

Other observations are more exportable: in Dufftown, Speyside, which proclaims itself the “malt whisky capital of the world” and is home to the Glenfiddich Distillery, the community gathers in the town square to enjoy drams of whisky and delicious pieces of shortbread.

The biggest celebration of all is in the Scottish capital of Edinburgh, where up to 50,000 people carry wax torches through the streets on December 30.

The following night sees the Ceilidh, a massive open-air party with plenty of traditional Scottish music and dance. Yet it’s curious to note that, unlike Lunar New Year, the Western New Year’s tradition revolves more around saying goodbye to the last one than saying hello to the next one. This is never more apparent than when, in a whisky-induced haze, we stand up/slouch sideways to sing Auld Lang Syne.