Then & Now | From taxi dancers to dancing aunties, inside Hong Kong’s shadowy underworld of paid female companions

- How the classy ‘taxi dancer’ (mo lui) ballrooms of the 50s made way for sleazy 80s discos, and eventually the suggestive ‘dancing aunties’ (dai ma) still polluting pavements today

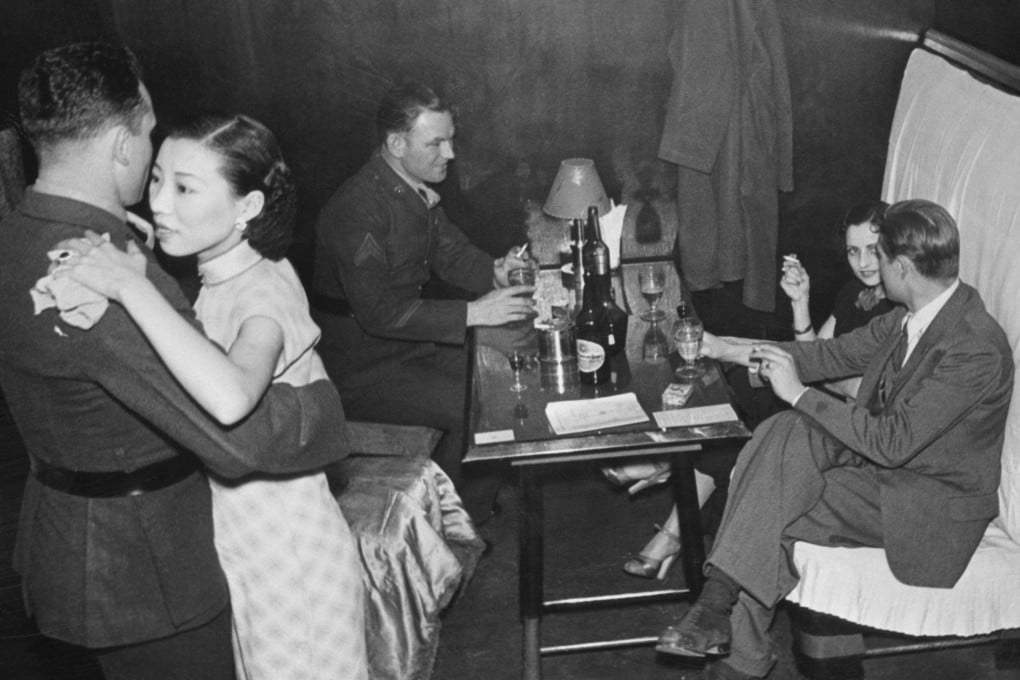

For several decades, some of Hong Kong’s best-known nightlife images featured slinky taxi dancers, known in Cantonese as mo lui. Invariably clad in figure-hugging cheongsam, these women were a key local ballroom attraction; the entire business model for these venues relied upon their nightly presence.

A ballroom’s taxi-dancer system worked like this; a patron bought a set of dance coupons, which were each good for one dance set. He presented a ticket to his choice of partner, who then danced that particular number with him. Also included in the price was the opportunity for a few minutes’ conversation. When the music stopped, both taxi dancer and patron left the floor; another ticket had to be produced should he want to dance the next number with her. Patrons could sit and chat after each set – if she wanted to – but if that happened, the ballroom’s management usually insisted that a “lady’s drink” be bought; generally, this was an expensive goblet of cold tea.

Many – but by no means all – were actually prostitutes. Any “extras” that may have been quietly negotiated with her dance partner always took place after-hours, and strictly off the premises. Others were office workers who liked getting dressed up for a night on the town, with the evening’s food and drinks fully covered by their dance partners (either directly, or through various “extras” hidden within their dance-hall entrance fee) and – best of all – get paid for dancing.

Nevertheless, this occupation was never one that respectable girls from good families (who, ultimately, had to consider their reputation and eventual marriageability) could easily enter into – or depart from – once they had started.

Some mo lui maintained an outward display of “respectability” by going everywhere with their personal servant; the dance hostess immaculately turned out in a shimmering cheongsam, and her Cantonese amah clad in starched white blouse and black trousers.

The lucky few eventually became a wealthy patron’s concubine; at least one elderly Chinese entertainment mogul – no prizes for guessing who – later married his favourite mo lui. Less-fortunate taxi dancers – as the years trudged on – eventually became nightclub managers themselves.