The myth behind the Dragon Boat Festival began with a poet’s death. His work lives on

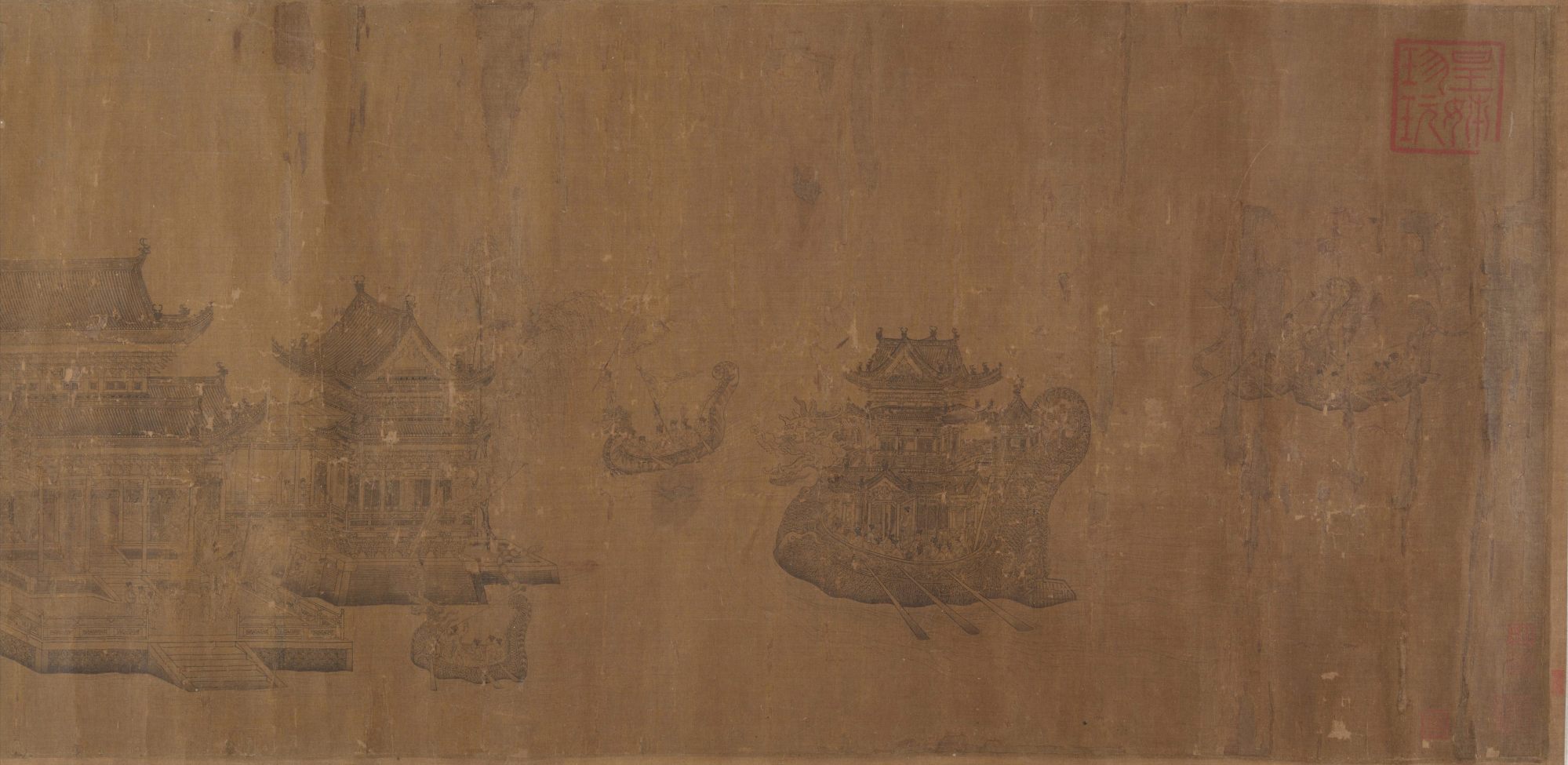

- In exile, poet and statesman Qu Yuan wrote an influential Chinese poem. His death in 278BC sparked the myth behind the Dragon Boat Festival

For East and Southeast Asia, the fifth day of the fifth lunar month is Tuen Ng Jit (Cantonese) or Duānwǔjié (Mandarin).

Ng/wu refers to the sun’s position at its highest point, and tuen/duan means “extreme, upright”, referring to the summer solstice.

Its origins in Chinese mythology are darker: it commemorates the suicide in 278BC of Qu Yuan (屈原), a well-loved poet and statesman of the Chu kingdom, during the Zhou dynasty’s Warring States period.

A champion of political loyalty and truth, Qu Yuan advocated resistance to the hegemonic Qin state – which led to jealous, corrupt rivals’ accusations of treason, and his subsequent banishment.

During Qu Yuan’s exile, he penned what is regarded as the most innovative and influential work in the history of Chinese poetry, Li Sao (離騷).

An extended political allegory, it is hailed for being the first in several aspects, including extensive dialogue with multiple characters as a poetic device, and complex imagery involving landscape and flora:

“The three kings of old were most pure and perfect:

Then indeed fragrant flowers had their proper place.

They brought together pepper and cinnamon;

All the most prized blossoms were woven in their garlands.”

It also exploits puns and double meanings, including with its title.

Traditionally rendered as “Encountering Sorrow”, Li Sao is suggested to have four readings: leaving or encountering trouble, or, with the character sao interchangeable with a homophonous character meaning “stench”, also encountering or leaving the stench.

Great poetry persists when sentiments have relevance across time and space. The despair conveyed through the first-person persona in the four-line conclusion surely resonates worldwide today:

“Enough! There are no true men in the state: no one understands me

Why should I cleave to the city of my birth?

Since none is worthy to work with me in making good government,

I shall go and join Peng Xian in the place where he abides.”