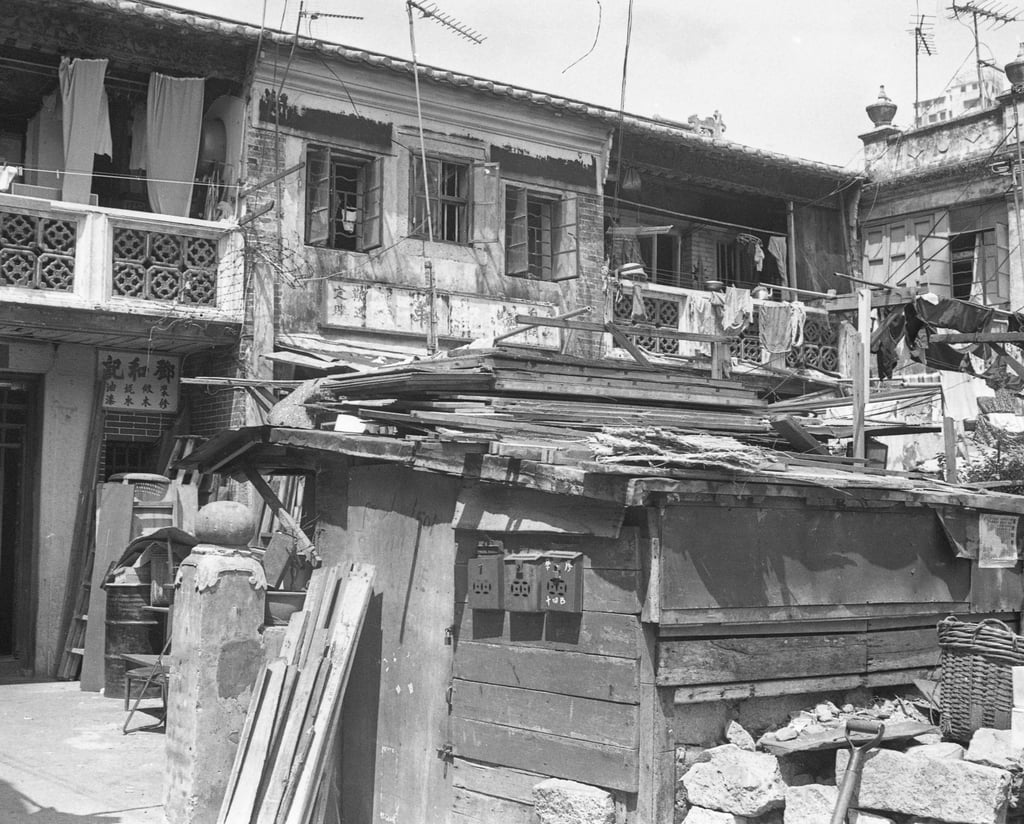

Then & Now | In Hong Kong, working from home was once lot of society’s poorest and most disadvantaged

- During the city’s post-war industrial boom, piecework was commonplace in local industry

- Such work-from-home arrangements allowed manufacturers to flout safety and labour regulations

Throughout months of pandemic-induced restrictions, city- or nationwide lockdowns, and intermittent office closures, working from home in one form or another has become commonplace all over the world. But what did this employment variant look like in the past, in Hong Kong and elsewhere, and how have the socio-economic realities for stay-at-home workers shifted?

Physical separation between workplace and home has largely evolved in industrial societies over the past three centuries. Before then, from the dawn of settled human life 10 millennia ago, the overwhelming majority of work was done at or close to home.

In agrarian societies, little practical division existed between work and home – tasks that needed to be done were done, day or night. For subsistence farmers, the “daily commute” meant a walk between house and fields, via animal pens, fish ponds and orchards.

With the beginnings of Europe’s Industrial Revolution, in the 18th century, residential clusters developed around emergent iron foundries, textile mills and other large-scale enterprises. Living conditions for workers in these industries were grim, and were a significant reason for emergent political ideologies – Marxism was merely one – that demanded radical social change, which in turn ignited successive revolutions from 1789.

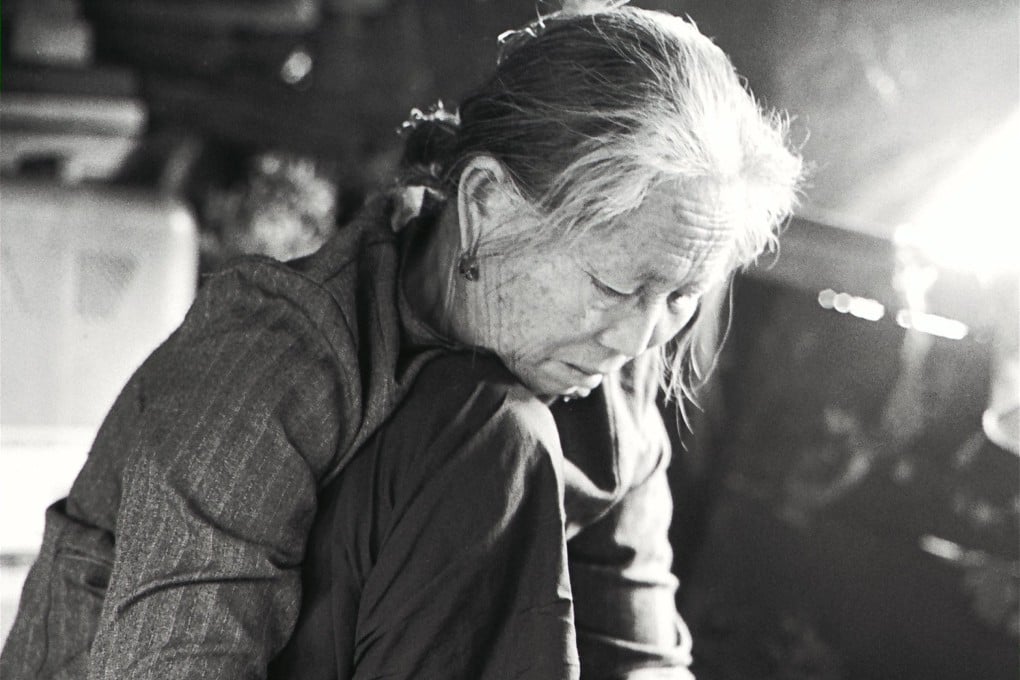

This was especially the case when there were children at home too young to be cared for by older siblings, or where chronic ill health or physical disability did not permit regular, strenuous outside employment. Boxes of unfinished items were delivered to a worker’s home by manufacturers and their agents, and then collected when completed.