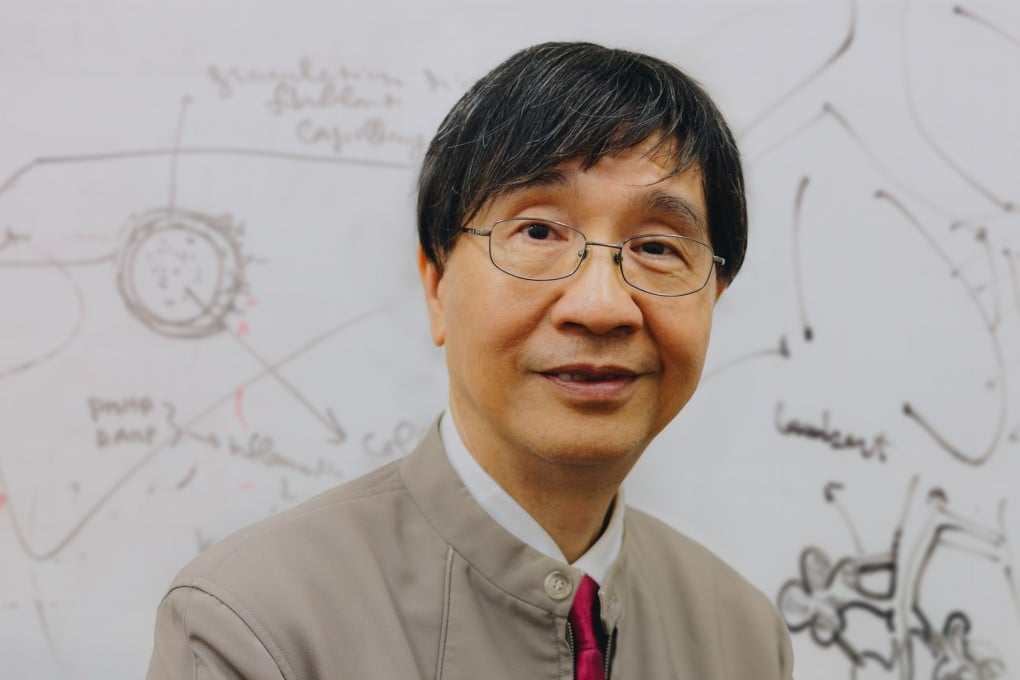

‘Hong Kong’s Dr Fauci’, Yuen Kwok-yung, on growing up poor and weathering Sars and Covid-19

He had an impoverished childhood, but went on to become world-changing infectious-disease scholar – Yuen Kwok-yung tells PostMag why we can expect the next pandemic within a decade

My mother was 16 when she arrived in Hong Kong in the 1950s, fleeing famine on the mainland. Not long after she arrived, she met my father, who had also escaped the famine. They married in 1954. My birth is recorded as December 30, 1956, though my mother insisted that I was actually born a few days later, on January 1. Perhaps a mistake was made in the paperwork over the public holiday. My mother was illiterate and we didn’t have the money to give red packets to the nurses and midwives as was expected.

Beyond basic

For the first two years of my life, I lived with my parents and older brother in a 60 sq ft room overlooking Wan Chai Market. My father was an apprentice under a dentist and worked 16 hours a day. Then we moved to Sai Ying Pun, where my two younger brothers were born. The living conditions were very basic. There were no toilet facilities – you urinated in the kitchen in the floor drain. Faecal material was collected in a bucket and at midnight sewage collection tanks collected the waste for the whole floor.

Great expectations

In poor areas, all you hear is family abuse. My father wasn’t like that, but I heard men who lived on our floor come back in a bad mood or when they’d lost all their money gambling and hit their wife and children. That was common and the atmosphere was oppressive. Across the road was a restaurant called Yung Kee. When I was three or four, I used a pencil and paper to write down the name of the restaurant. No one had taught me how to write those two complex characters. My mother was amazed at what I’d done, and I think that’s what made her have such high academic expectations for me.

Traditional remedy

We visited my grandfather, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) doctor in Guangdong province, for the summer holidays. When I was in Primary Two, a patient arrived, carried by his relatives. Western doctors had said he had liver failure and would die, and they wanted to see if TCM could help. My grandfather felt his pulse, placed a (TCM) tablet under his tongue and put acupuncture needles all over his body. After an hour, the patient woke up, to the amazement of everyone. My grandfather said that if he responded to the TCM potion, he could come back every week and try more. Every time he came, he brought ducks, chicken, geese and vegetables as a present. Of course, I enjoyed the food.