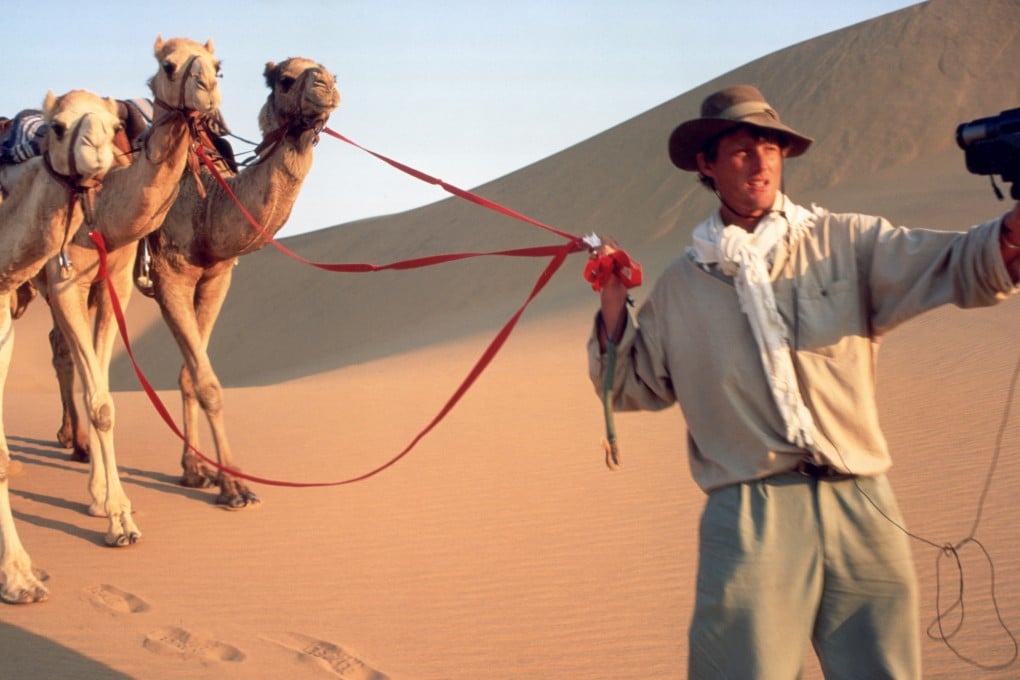

‘I had to eat the dog’: explorer Benedict Allen on his adventures, the scars on his chest and being ‘lost’ in the jungle

- The explorer and writer tells Ed Peters about the time the media had to ‘rescue’ him, having to eat his canine companion and the ritual scars on his torso

Wanderlust is part of my family inheritance – many of my forebears went to India and other foreign parts – but I was born in not terribly exotic Macclesfield, just south of Manchester, in England, in 1960. My father was a test pilot involved in the development of the Royal Air Force’s Vulcan bomber.

I read environmental science at university, and took time off to join expeditions to a volcano in Costa Rica, a forest in Brunei and a glacier in Iceland, all of which whetted my appetite to go somewhere even more remote and – preferably – on my own.

Mad white giant

Aged 22, I came up with the idea of trekking through the forest between the mouths of the Amazon and the Orinoco rivers, in Brazil. There were no maps, so I was going to have to navigate myself, and there was no sponsor so I worked in a warehouse to get some funds together.

I’ve been (briefly) shipwrecked off Australia, and had to stitch up a chest wound with a bootlace in Sumatra. No anaesthetic, either