Chinglish: Sue Cheung revisits the racism, trauma and humour of growing up in a Chinese takeaway in Britain

- Sue Cheung’s humorous book Chinglish has received critical acclaim, but writing it meant revisiting the often unpleasant experience of her childhood

When Sue Cheung was growing up in England during the 1980s, she believed her family was the only one in the entire world that lived in a Chinese restaurant. “Because we didn’t have the internet back then, we all thought we were alone,” she says. “We all thought we were living in these takeaways and experiencing these kinds of lives all on our own.”

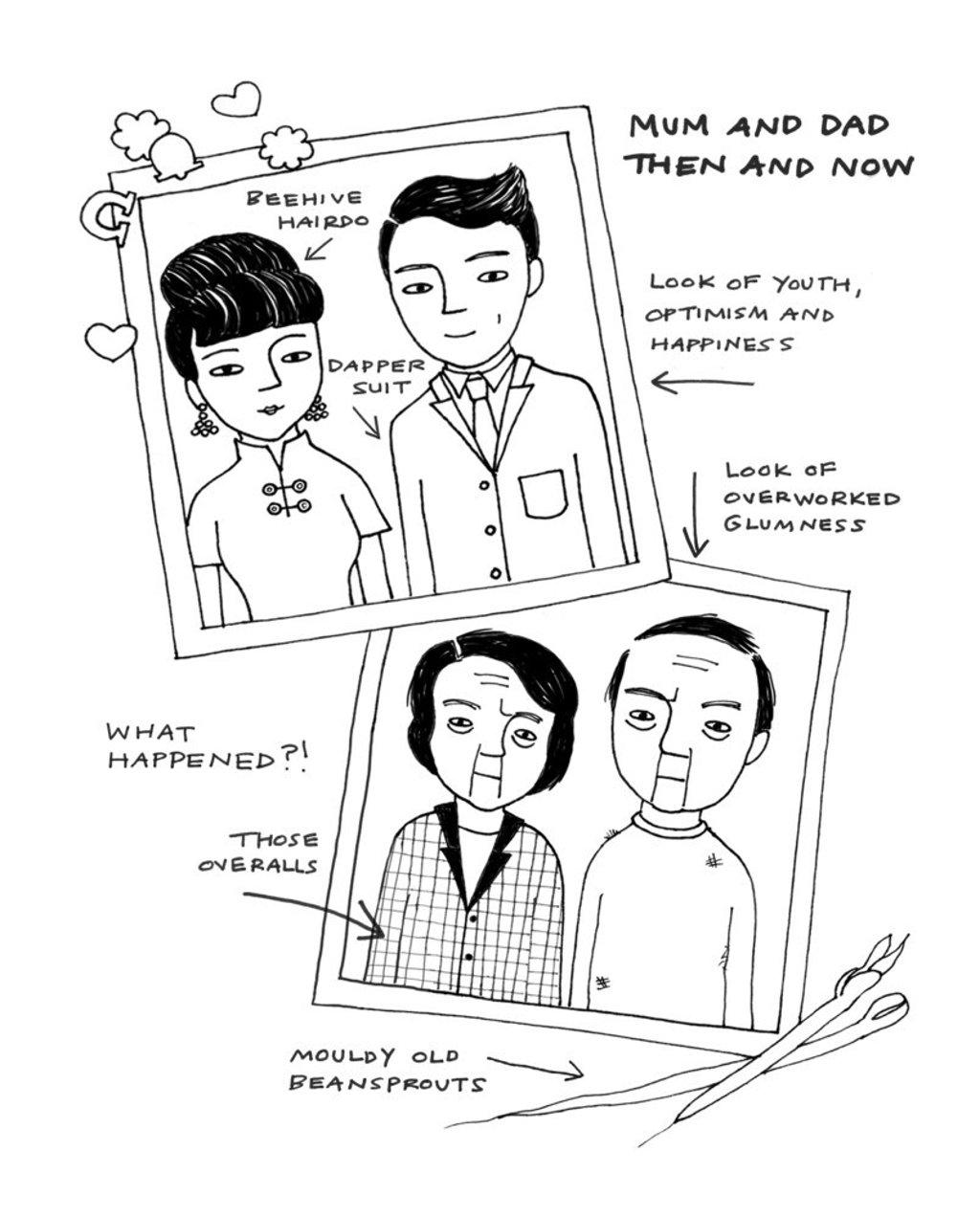

The way Cheung tells it, her childhood would have been isolated even with the benefit of 21st century social media. Her parents emigrated to England from Hong Kong in the 1960s, and found themselves strangers in an indifferent, often racist and occasionally hostile land. Their own reluctance to speak English did not help matters, nor did their refusal to embrace English culture in any way.

But perhaps the biggest barrier separating the Cheungs from the world around them was the restaurant itself. “My parents worked every single day – apart from Christmas Day,” Cheung recalls.

She was expected to muck in from an early age. This meant helping out in the kitchen. Later she would serve customers the moment she arrived home from school. “You never had a break. There was no social life. You never left the takeaway – especially if you lived above the shop. You never even left the building,” she says.

All of which might explain Cheung’s utter bemusement 30 years later, when she was told, by her literary agent, that her experiences would make a brilliant book. After a career in advertising, Cheung had begun writing and illustrating children’s picture books. Dreaming up stories about kindly aliens was one thing; transforming her own childhood into popular entertainment was something else entirely. “Who is going to want to know about a working-class girl growing up in a takeaway in Coventry?” she reasoned.

Lurking beneath this scepticism were reservations of greater significance. Writing about her family would not only involve raking over years of racial abuse, alienation, loneliness and boredom, it would mean confronting a dark history of domestic abuse doled out by her own father, which eventually tore the family apart.