How the world caught up with media visionary Marshall McLuhan

The Canadian professor, philosopher and oracle of 1960s counterculture foresaw humanity’s ‘march backwards into the future’ as we are consumed by our digital landscapes

For much of 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic disrupted our physical reality, equally dangerous pathogens surged unchecked through our digital mediascapes. The technologies that promised to bring the world together have ruptured, exposing an unstable, corruptible core where conspiracy and prejudice thrive. It is a far cry from the enlightened digital utopia the internet was thought to be capable of facilitating early on. Instead, the inverse situation seems far more prevalent.

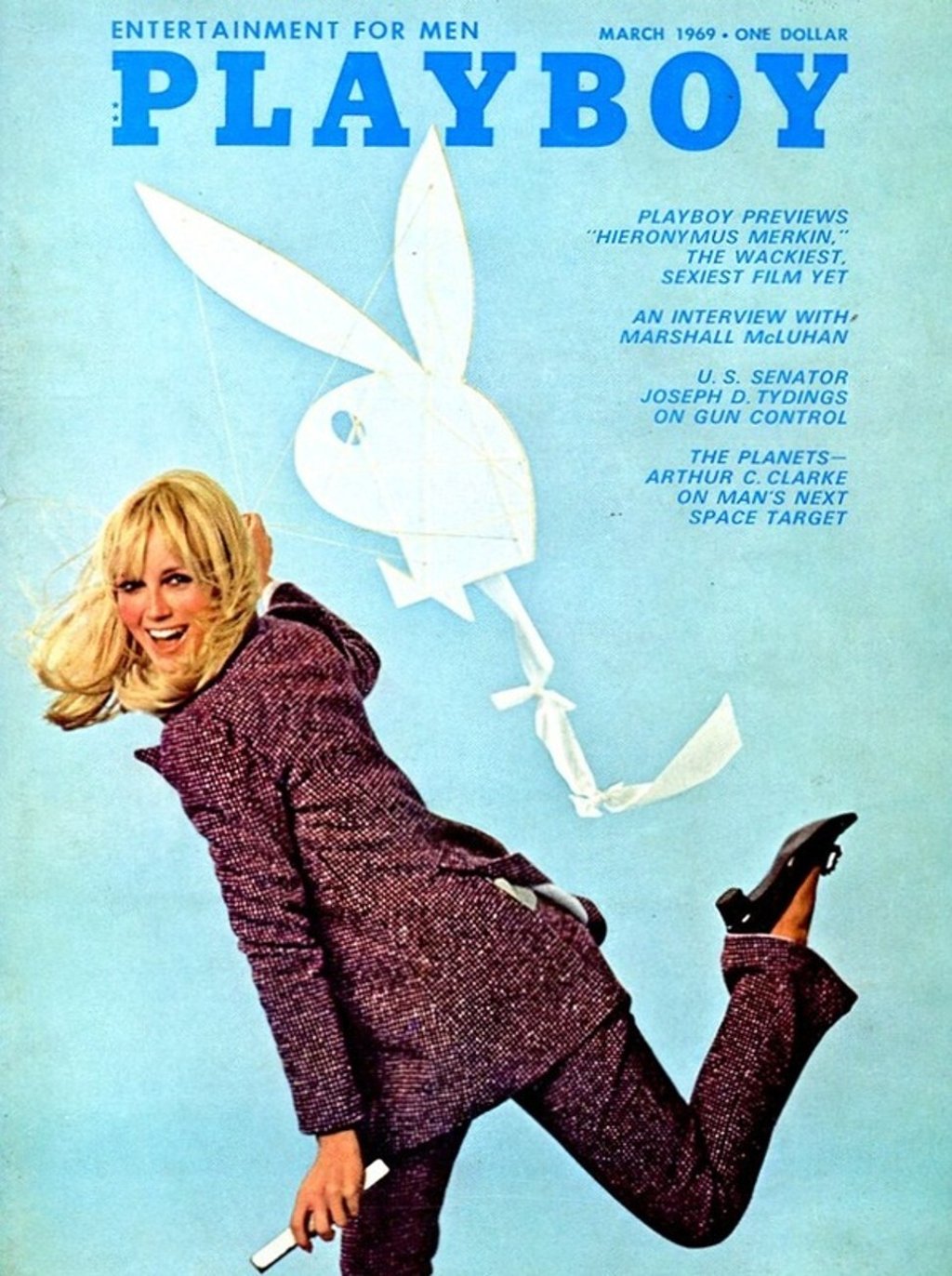

So in 2021, as we attempt to remedy viruses both biological and technological, it could pay to revisit the work of professor and philosopher Marshall McLuhan, the oracle of 1960s counterculture who predicted the dysfunctional state of our current media, despite drawing his last breath in 1980 – a decade before Tim Berners-Lee published the first-ever website.

McLuhan’s work sheds much-needed light on the widespread effects of contemporary media in both the East and the West; reveals a number of fascinating connections to ancient divination text the I Ching (Book of Changes); explains the revival of classical Chinese literature as an effect of our digital world; and opens up startling new perspectives on future communication technologies. And that is just scratching the surface of his legacy.

Now, almost 60 years after his classic works were published, the strait-laced Canadian has left us with as good a road map as any for navigating a 21st century media dominated by Machiavellian algorithms, rampant disinformation and metrics-driven emotional manipulation. As McLuhan himself cautioned, his famously coined “global village” would not be “the place to find ideal peace and harmony”.

“Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world has become a computer, an electronic brain,” he wrote about what would have passed for big data in 1962. “And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside.”

As early as 1960 he described the world as “a continually sounding tribal drum, where everybody gets the message all the time. A princess gets married in England and ‘boom boom boom’ go the drums – we all hear about it [ … ] A Hollywood star gets drunk, away go the drums again.”