What is CRISPR? The gene-editing technology carries much promise – and peril – amid pandemic

- As the battle against Covid-19 intensifies, one scientist calls CRISPR ‘our power pellet to help us fight this horrible virus’

- The genome-editing tool could indeed bring an end to disease and drastically improve our lives, but with it comes the spectre of bioengineered abomination

The campus of Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), in the United States, could double for a spectacular fortress, lifted from the pages of a medieval European romance, extruding squarely from Portland’s bucolic Marquam Hill – “pill hill” in the local argot – overlooking the Willamette River valley towards a horizon buckled by the snow-capped monolith of Mount Hood, around which more local legends abound.

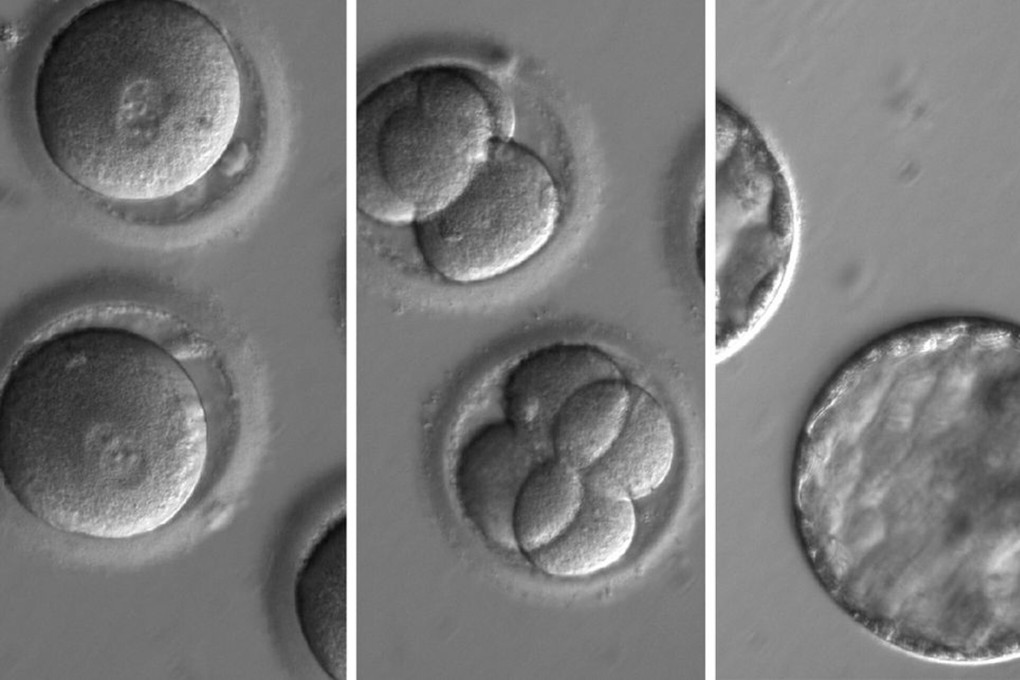

But it is the idea of a therapeutic Camelot that makes OHSU a fitting site for what may turn out to be one of the 21st century’s most legendary biomedical procedures. Here, on the eve of Oregon’s coronavirus lockdown, the gene-editing toolkit known as CRISPR, a potential holy grail in the quest to banish disease from the human condition, was deployed under trial, “in vivo” – in a living human patient – for the first time.

Just as the novel coronavirus, which had brought large swathes of China and Europe to a standstill, began its wildfire migration through the wider US, a benign virus re-engineered to carry its cutting-edge CRISPR payload was injected into the eye of BRILLIANCE trial participant #1 at OHSU’s Casey Eye Institute. The goal: to treat and hopefully reverse the most common cause of inherited childhood blindness, Leber congenital amaurosis.

“Time slows down,” says Dr Mark Pennesi, chief of the Ophthalmic Genetics Division at the Casey Eye Institute, and primary investigator of the trial. “You watch the surgeon take this very, very tiny needle and just barely put it a few microns beneath the retina to inject the gene therapy product. It creates a little blister and it slowly grows. You’re holding your breath … and then it’s done and everyone exhales.”

News of the landmark procedure was announced, without much fanfare, at the beginning of March. By late summer, while the success of the operation had yet to be determined and its place in medical legend was still to be etched, the unnamed trial patient was reported to have experienced no significant complications, but Covid-19 dominated the news cycle.