Urban Indians took their domestic workers for granted until, under the coronavirus lockdown, they had to do the housework themselves

With lockdown denying them their domestic helpers, many middle- and upper- class Indians have had a rude awakening to household chores, setting social media alight with pictures and videos of affluent folk tackling floors, food and family care with new-found respect, if not skill

On March 22, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi implemented a janta curfew – the people’s curfew. Everyone was to stay indoors from 7am to 9pm and observe social distancing to help fight the coronavirus, which at the time sat at just over 300 reported cases in the country (current numbers are well past 70,000).

But there was more at work than Modi’s usual calls for patriotic tokenism: the mass lighting of candles, the clanging of pots, or in this case, five minutes of clapping for health workers, frontliners fighting the good fight against this global scourge.

Indians, unfazed by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s latest play in childish tribalism, and who knew the virus’ incubation period was as long as 14 days, not just 14 hours, understood that the janta curfew was useless – except as a primer in national solidarity for what would be the sudden sequestration of the country’s 1.3 billion people.

02:14

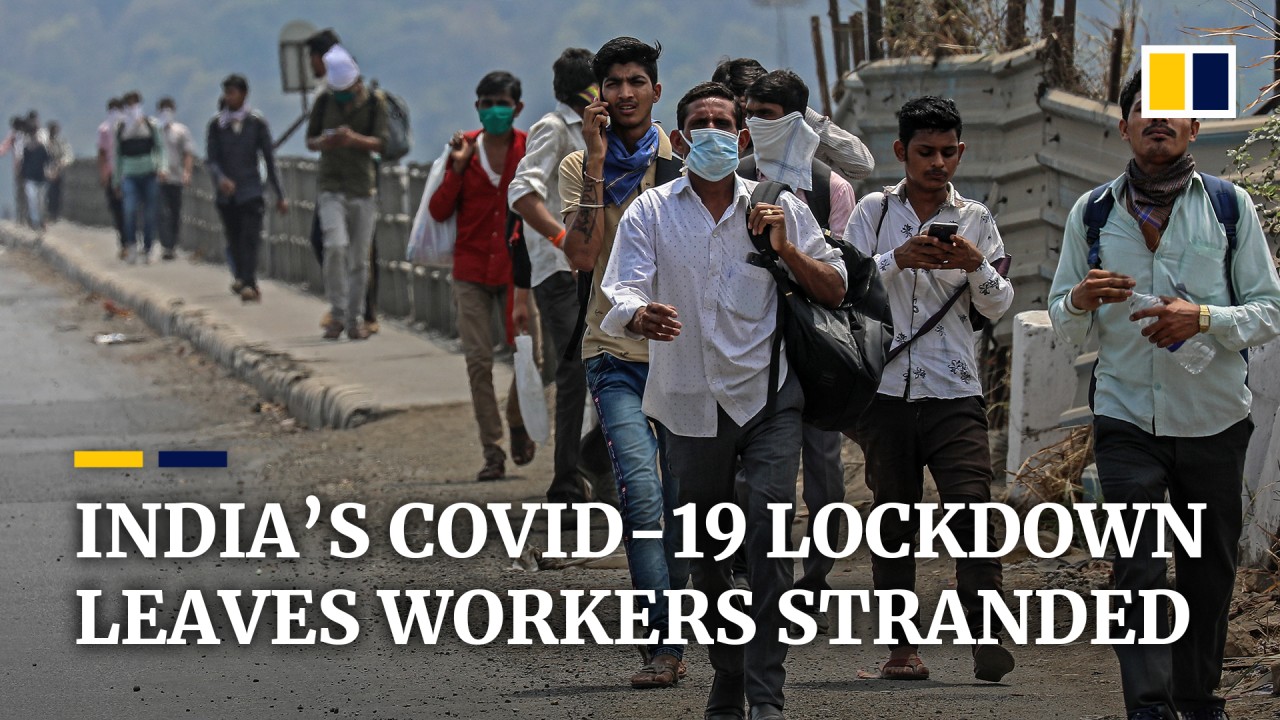

There was little time to stock up on supplies. There was no clarity regarding the rules of movement. Those travelling were now stuck wherever they were, no matter how far from home. Thousands of migrant workers and daily-wage earners walked hundreds of kilometres to return to their homes and families they had left behind to find work in big cities such as Delhi. About 300 deaths have been linked to this forced exodus of those with nowhere of their own to self-isolate.