Chinese immigrants went to Australia looking for gold and found communities. Why does so little of their legacy remain?

Driven off Queensland’s goldfields, arrivals from China pioneered trade and agriculture in the north of the country, until discriminatory legislation and changing times forced them out

Gold fever hit Australia in 1851. Rushes swept the southern states of Victoria and New South Wales and fanned out across the country; whole towns emptied as people raced to the goldfields, hoping to “strike lucky” and make their fortunes. As news reached the outside world, Australia was overrun by migrant prospectors from Britain, Europe and, especially, China.

At the time, China was in chaos, ravaged by famine and civil war, and many Chinese came to the Antipodes from harsh rural backgrounds. With little to lose, they were willing to work hard for profits they could either send home to relatives or save for their own return. Mostly male, immigrants were divided by a range of dialects and clan loyalties, united by being strangers struggling to survive in a foreign and often unwelcoming land.

In far north Queensland, where Australia’s “finger” points towards New Guinea, so many Chinese came that, at one time, they outnumbered the European population by five to one. Many remained long after the gold had gone, pioneering local trade and agriculture and bringing substantial improvements to living conditions. And yet little trace of this Chinese heritage remains today.

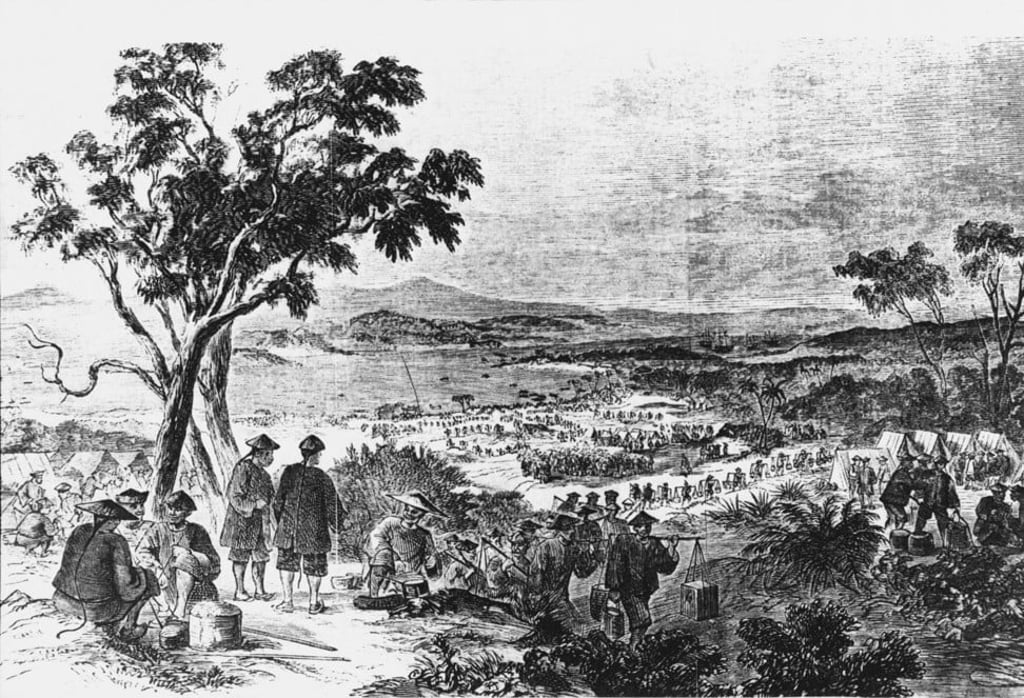

In 1872, gold was discovered in far north Queensland’s remote Palmer River, a harsh country of open woodland, savannah and granite outcrops where temperatures top 40 degrees Celsius in summer. It was also home to Aboriginal peoples, who resented outsiders pouring into their territory, stripping the land of its resources. Violent exchanges between the two groups ensued, with fatalities on both sides.

Still the prospectors came in their thousands. Mining camps sprang up at Palmerville and Maytown, and the gateway coastal port of Cooktown was founded 140km to the northeast.

The Palmer became Australia’s richest alluvial goldfield: the government warden recorded one prospector finding nuggets weighing 179oz (5kg; worth US$262,000 today) in just three hours, while another team panned 59lbs (26.8kg) of gold in three weeks (US$1.26 million).