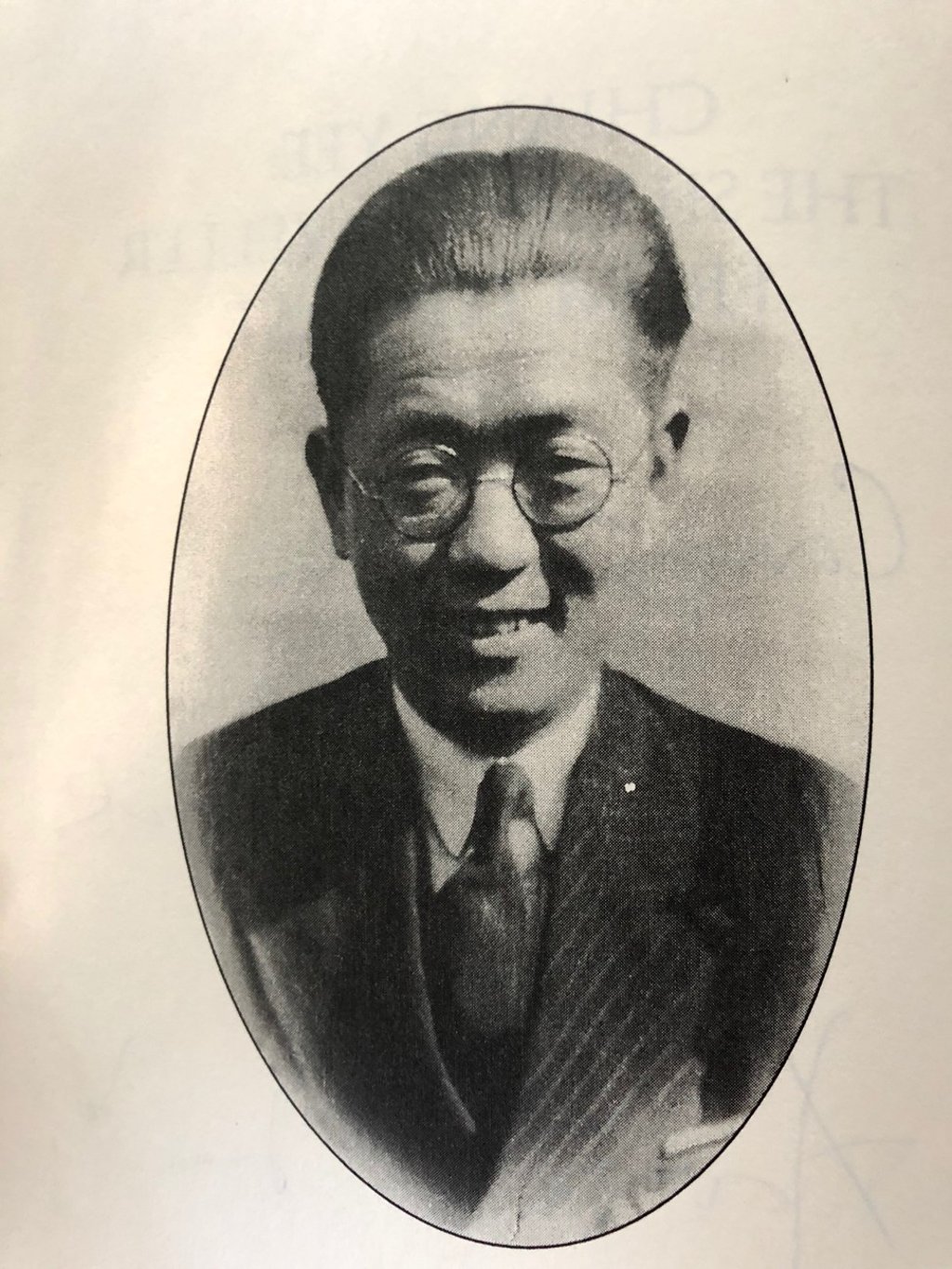

Chinese artist and author Chiang Yee takes rightful place in British cultural history

- The Jiangxi-born author of the Silent Traveller series of books showed wartime Britons a unique view of China

- He is honoured by a blue plaque on the facade of the Oxford house in which he lodged, lived and worked for 15 years

In the summer of 1940, Chiang Yee knocked on the door of 28 Southmoor Road, Oxford. It was opened by Henry and Violet Keene, who offered the traveller a bedroom on the upper floor of the unassuming terraced house, and the front room facing the quiet residential street as a study.

Chiang had arrived in the British university city after being bombed out of his lodgings in north London during the blitz of World War II. Moving from door to door and asking for a room for the night, what he thought would be temporary lodging became his home for the next 15 years, during which time he honed his extraordinary artistic ability and prose, writing about the British and painting scenes of their country.

Chiang’s observations secured him a place in the hearts and minds of Britons who looked to him for insights into the mysterious Middle Kingdom, while he in turn looked to them for traits he believed to exist in all of us, regardless of race or nationality.

“I am an Oriental,” Chiang wrote in the introduction to his third book, The Silent Traveller in London (1938), part of a series that would earn him legions of Western fans, “I am bound to look at many things from a different angle. But is it really so different? I very much doubt it myself […] I have never agreed with people who hold that the various nationalities differ greatly from each other. They may be different superficially, but they eat, drink, sleep, dress, and shelter themselves from wind and rain in the same way. In particular their outlook on life need not vary fundamentally.”

It was his belief in the universality of nature and his quest to find close contrasts between his homeland and abroad that spawned some of his finest work – a prodigious body of art that spanned into ballet and children’s books, and all showcasing Chinese culture directly to Western audiences.

And now, more than 40 years after his death, with a new generation facing new tensions between East and West, a band of academics, writers and readers, have given Chiang the recognition they believe he deserves. It is an honour usually reserved for the likes of legends, and the locations in which they lived in Britain: Arthur Conan Doyle in Westminster, John F. Kennedy in Kensington, Karl Marx in Camden. And Winston Churchill, of course.