Hong Kong’s ‘recreational clubs’ are remnants of its colonial past; what does that mean for their future?

- The Victoria Recreation Club has survived wars, typhoons and benign dictatorship, but now, after 169 years, it must face its biggest challenge – the changing demands of a much altered Hong Kong

Crowded by a tangle of trees, the entrance could be that to a ghostly theme park. The heraldic emblem on the gate features two crossed flagpoles, each standard bearing the cross of St George and the enigmatic letters “VRC”. Other signs warn “Members Only” and “No dog is allowed” in English and Chinese, and potholed concrete tracks wind towards a clubhouse hidden beneath a mass of acacia, ficus, flame of the forest, camphor and maple trees, many damaged by the recent Typhoon Mangkhut.

At the end of the driveway lies a small car park, some potted plants, that crossed-flag emblem again, and the main clubhouse of the Victoria Recreation Club, founded in 1849.

The clubhouse itself – a cubist confection hidden away in Tai Mong Tsai Tsuen, in Sai Kung Country Park, before the Pak Tam Chung barrier, in the New Territories – is not so old, dating only to 1966. Walk through its doors, and down a long flight of steps to a rocky beach, and there one might be greeted by laughter, the clinking of glasses of white wine, and children wading in the waters of Emerald Bay against a backdrop of gumdrop islands. Some guests will remember when they themselves played here as children. Others might wheel their elderly parents under the trees and through the boatyard to the beach.

The VRC’s peaceful setting belies the controversy in which it and Hong Kong’s 23 other “private sports clubs” (as the government describes them) now find themselves, victims of skyrocketing property prices and an identity crisis that pits legacy against the rapid pace of the city’s integration with mainland China.

The 24 clubs benefit from heavily subsidised private recreational leases. Other, even grander clubs that have different lease structures, some effectively in perpetuity, such as the Hong Kong Club and Shek O Country Club, have discreetly kept their heads down. But all of them face a cultural wave in which their core purpose is being challenged.

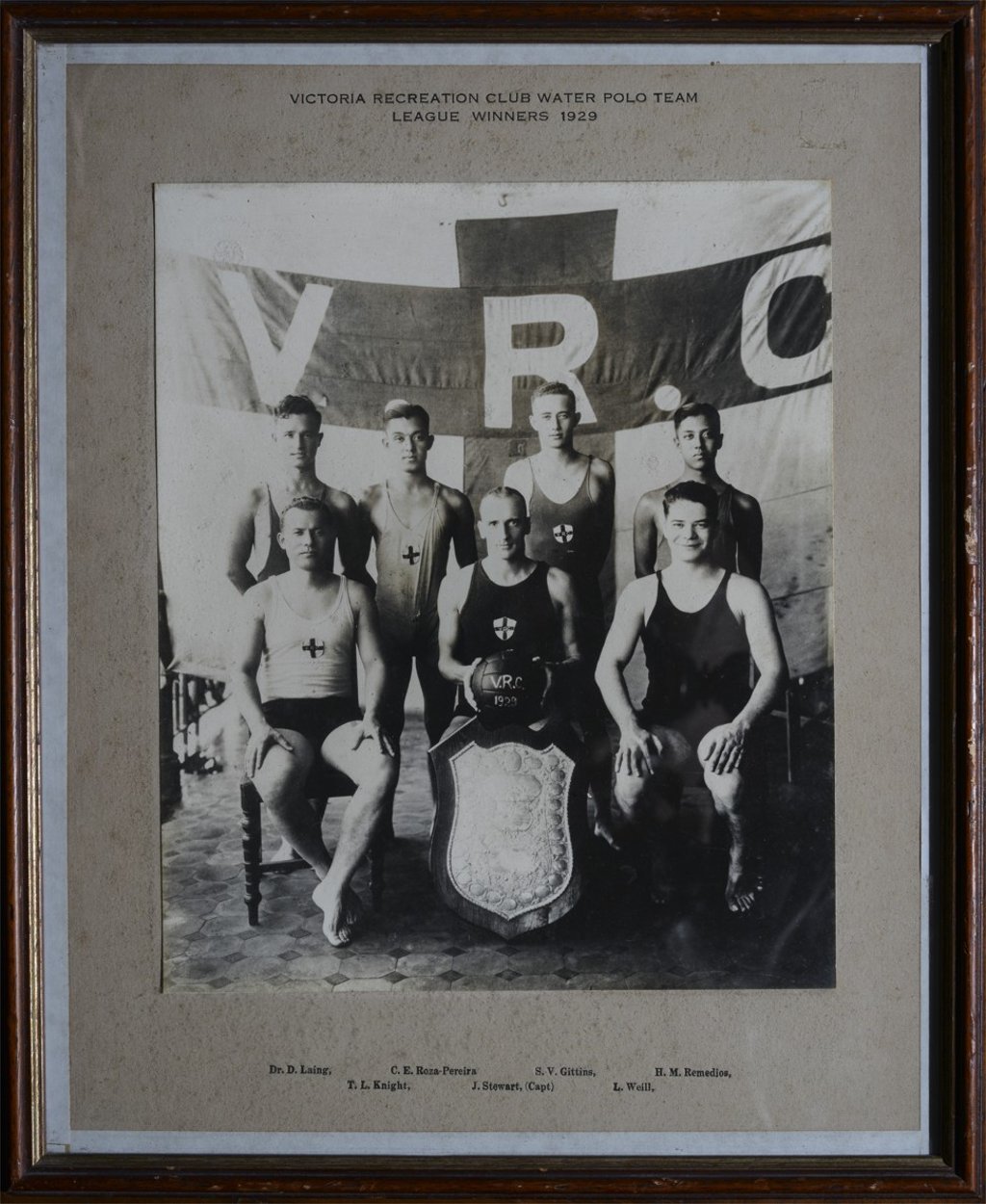

the colonial society into which the clubs were born was hierarchical. British and white expatriates were at the top of the caste system, but it also served to knit together the diverse community of the British Empire, and to include Chinese, Eurasians, Portuguese from Macau, Sikhs and Parsees, Hindus, Jews and even smaller groups such as the Nepalese and Filipinos. As part of the empire, Hong Kong represented a vision founded on diversity.