On the trail of Deng Xiaoping in the French town where he embraced Communism

- In the 1920s, the man who would become China’s paramount leader found his raison d’être in unremarkable Montargis, 120km from Paris

- Students sent to France to learn from the West made the town a hotbed of Chinese Communist thought

Baoding is a sizeable city in central Hebei province, in north China, and synonymous with heavy industry and its attendant ills. Its hardy people – mostly of the country’s Han majority – wear no-nonsense expressions and display a hardheadedness born of stoicism. A showcase city Baoding is not.

Yet neither is it poor. As I walk the streets, the trappings of 21st-century capitalism protrude between the Mao-era tenements and identikit high-rise apartment blocks. There are fast-food joints, a few garish shopping malls and a railway station so big it makes those in Europe look like toy models.

Not far from the station, on Yuhua West Road, stands a large, unremarkable middle school that could exist anywhere in China. At the back of the school, on Jingtaiyi Road, a few Taoist fortune-tellers line the route to the gate of a small building fashioned in the Ming style. A sign above the door bears the calligraphic script of former Chinese president Jiang Zemin. It reads, Liu Fa Qingong Xianxue Yundong Jinnianguan, or, “The Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement Museum”.

The museum tells of aspirational young Chinese who went to France and Belgium to work and study a century ago, lured by the promise of acquiring the modern skills and technology with which they might help develop their motherland. The well-intentioned initiative lasted from 1908 to 1927, but ultimately failed due to the miserable conditions many of the Chinese endured, exploited at the hands of factory owners or deprived of the schooling they had been promised.

Despite the movement’s failings, and due to its celebrity alumnus (namely Deng Xiaoping, who would go on to become China’s paramount leader), the Mouvement Travail-Études has become central to Chinese Communist Party mythology, much like the Long March. Yet despite the propaganda element (posters recalling China’s century of humiliation at the hands of foreign imperialists, for instance), the museum’s curators have brought to light an often-skimmed-over chapter in modern Chinese history.

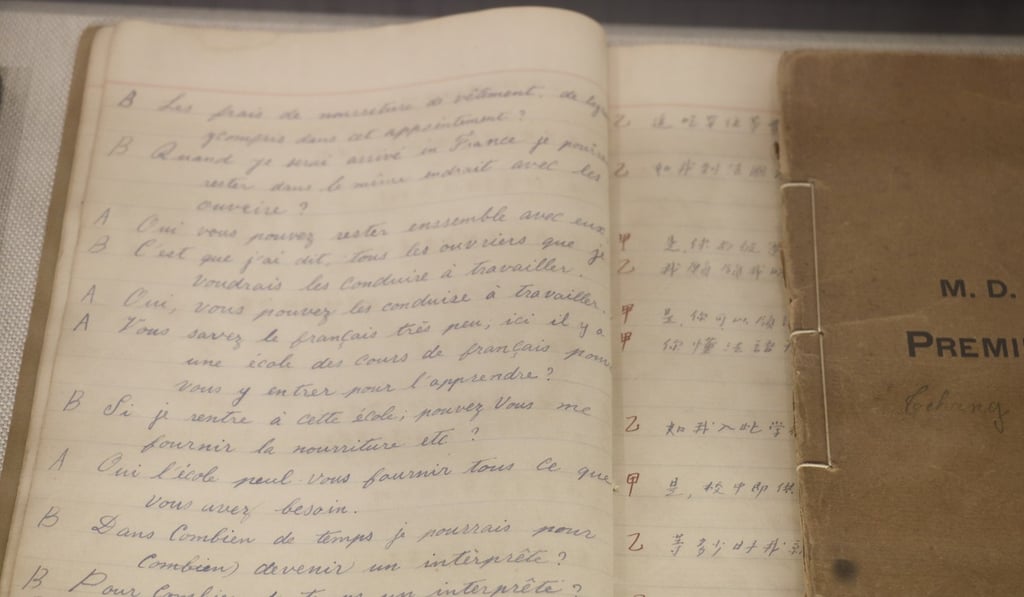

Heart-rending poems penned by homesick students adorn the walls; black-and-white photos show the youngsters in exotic French locales; and cases display exercise books containing handwritten French homework and moth-eaten diplomas from French universities.