Advertisement

Profile | ‘Being blonde was essential’: former model, PR and gossip columnist on a hairy Hong Kong junk trip with Joan Collins, corrupt police, and her jewellery line

- Karen Penlington Luard reflects on growing up in Hong Kong, the years she ‘practically lived in Lan Kwai Fong’ and the time Joan Collins nearly got blown up

- Her father was a Hong Kong government lawyer tackling police corruption, and she recently began research for a book about the ICAC, the city’s anti-graft force

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

2

I was born in Christchurch, New Zealand, but have spent vast swathes of my life riding the crest of a wave in Hong Kong – and what a ride it has been!

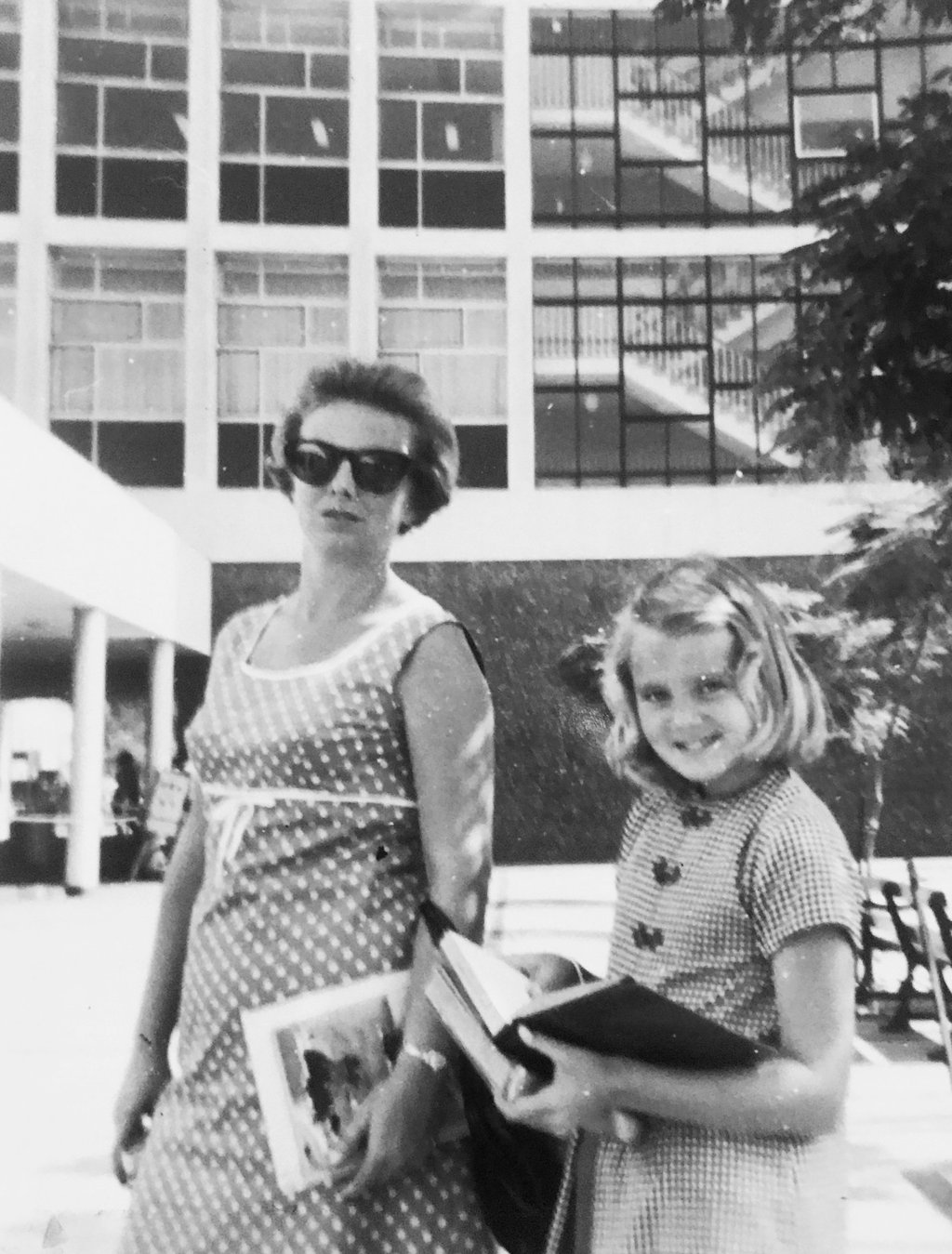

We – mum, dad and my younger sister – landed there in 1964 after five years in what was then Western Samoa. At first, we lived in the Merlin Hotel (behind The Peninsula, in Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon) and then in a government flat at Piper’s Hill just by what is now Lion Rock Country Park – we used to have fun chasing the monkeys that ran wild there, but not one we called The Big Chief who was nasty and stood his ground.

Later, we moved to The Peak on Hong Kong Island; I went to Island School in the former Military Hospital on Bowen Road.

I loved that building, but it was supposed to be haunted so it was scary on winter evenings. I hung out at the Ladies’ Recreation Club: lots of tennis and sunbathing by the pool and fun discos upstairs.

I was dispatched to boarding school in New Zealand in the 1970s. Once, when my dad, who was Crown Counsel in the Legal Department, was driving me to Kai Tak, I asked him why he seemed so preoccupied.

He said he had been working on the case of a corrupt policeman called Peter Godber, and they had asked him to explain all the [money] in various overseas bank accounts. He was on a “stop list” at the airport, but Dad was anxious. “It just all seems a bit too easy,” he said.

Advertisement