Architect I.M. Pei never wanted a retrospective. How Hong Kong got to host one at last

- M+ museum hosts the first major retrospective of I.M. Pei’s work. Curators and architect’s son tell the story behind it, and what to expect

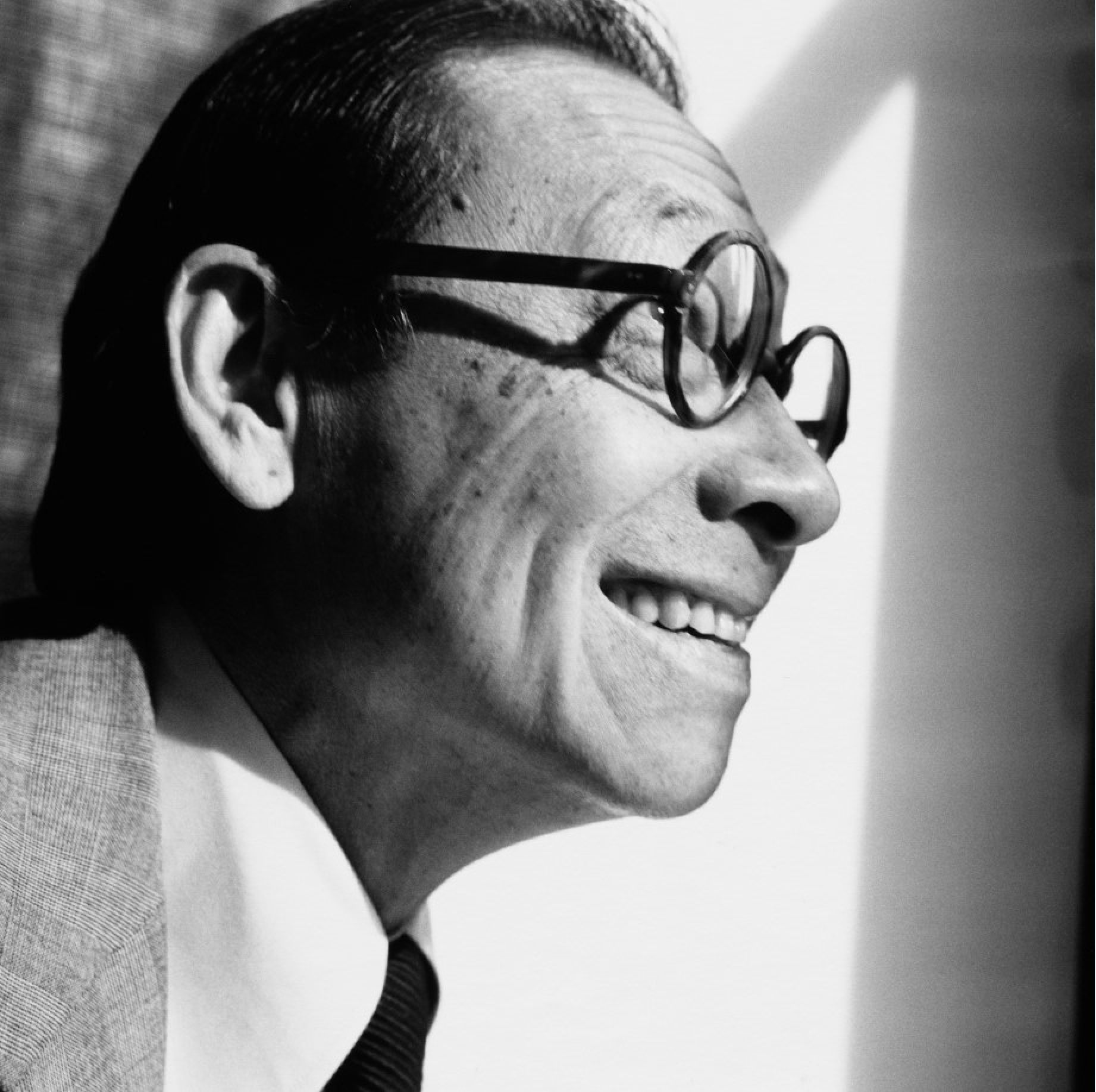

Think you know Ieoh Ming Pei? With his impish grin and trademark round spectacles, he was the father of such buildings as the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong and Paris’ Louvre Pyramid.

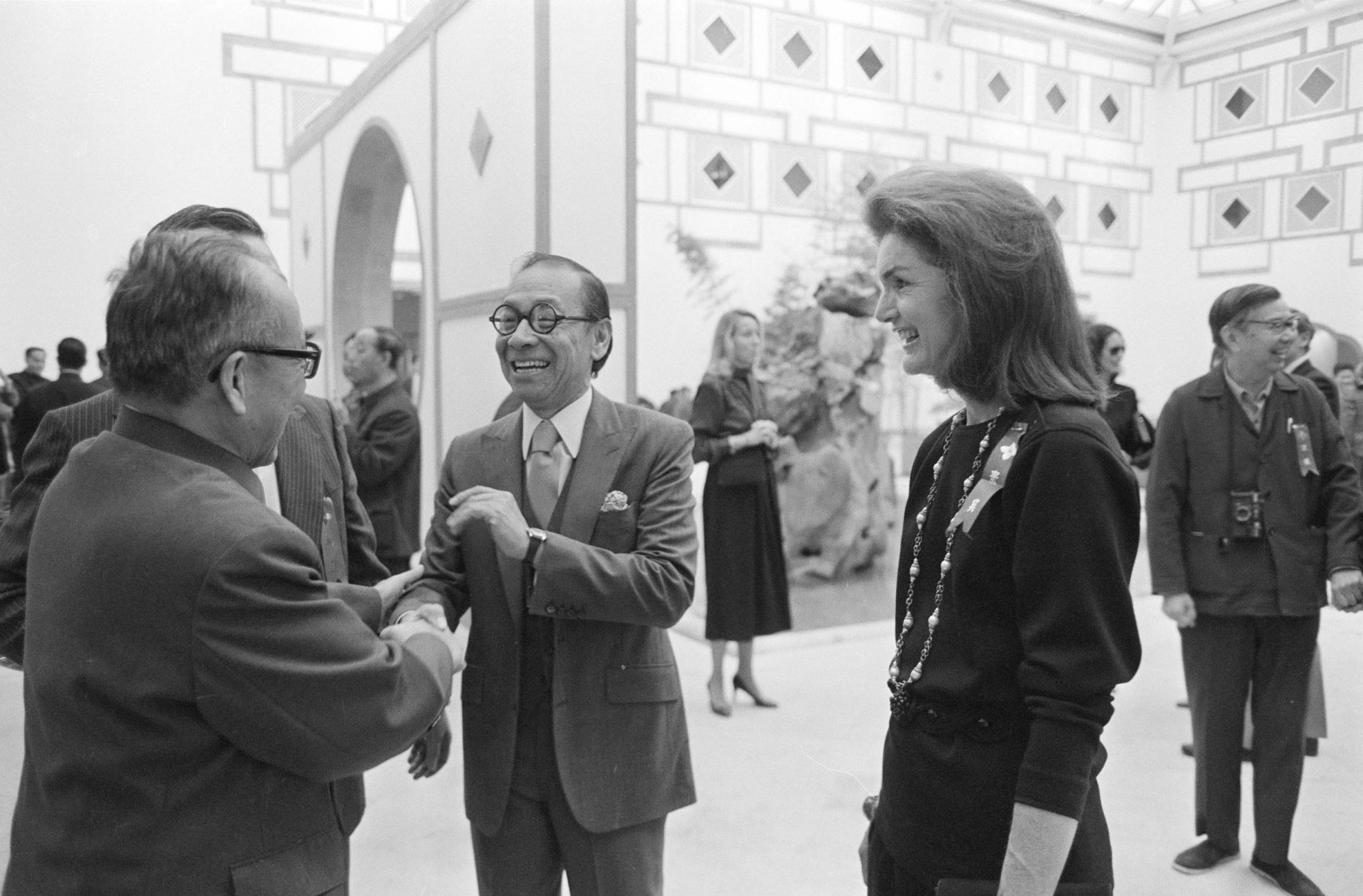

He was a foe to feng shui masters and bête noire of the French media, and was photographed with famous faces of the moment, including Jackie O, Robert Kennedy, Jimmy Carter and François Mitterrand.

He received the Pritzker Architecture Prize and numerous other professional honours, and was awarded the United States Presidential Medal of Freedom by George H.W. Bush. His obituary in The New York Times in 2019 described him as a “cultivated man [of] easy charm”.

Running from June 29 until January 5, at the M+ museum of visual culture in West Kowloon, Hong Kong, the exhibition is – extraordinarily – the first major retrospective dedicated to the Chinese-American architect. And the reason it took so long was largely Pei’s doing.

“He never wanted a museum retrospective,” says the exhibition’s co-curator, Aric Chen, the former lead curator for design and architecture at M+ and now the general and artistic director of Rotterdam’s Nieuwe Instituut.

“He was offered them, but he would say, ‘Why do we need an exhibition? Just go and look at my work!’”

Speaking during a video call with fellow co-curator Shirley Surya – M+’s curator of design and architecture – and Pei’s son, architect Sandi Pei Li-chung, Chen reveals that the Pei family supported the idea of an exhibition and that it did, finally, come with the blessing of the man himself.

“The family decided we could do this,” says Chen. “The conversation started in about 2014, when I was talking to Sandi about acquiring some of Pei’s work for the M+ collection.

“It was complicated, because he had already donated his personal archive to the Library of Congress, in Washington.

“But when I realised there had never been a real Pei show it was obvious we should do it. Pei [Snr] agreed; in fact, we have a letter stating his support. So it was all done properly.”

Sandi says it is fitting that the first extensive retrospective of his father’s work should be in Hong Kong, which he visited frequently.

“With my father emerging from China, I very much embraced the idea. When I introduced my father to Aric, [Pei Snr] expressed – I wouldn’t say enthusiasm – but he accepted the notion of an exhibition.

“This was towards the end of his career, so he thought, ‘Well, maybe I don’t have that many more buildings left to do.’”

A decade later, the exhibition, occupying six main and two subsidiary rooms at M+ and comprising more than 300 items, many displayed for the first time, has taken shape.

Exhibits assembled from the Pei estate, other private holdings and institutional archives, such as those of New York architectural firm Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, include architectural models, original drawings, films, letters, photographs and other objects with a Pei connection.

“There wasn’t a single item, apart from a lamp, related to Pei in the M+ collection. So we had to scour [for] everything,” says Surya, who steered the preparation of the exhibition after Chen left M+ in 2019.

“We want to acknowledge that we got approval from the right people, [such as] Henry Cobb, Pei’s partner, for access to the Pei Cobb Freed archive,” she says.

I think he’d be impressed by the exhibition. It’s much more in-depth than he might have imagined

That was then tackled with the help of Pei Cobb Freed historian Janet Adams Strong.

“She organised the materials, knew where they were, had a basic inventory,” says Surya. “We visited New York twice to see items before the pandemic hit, but Janet was the one, throughout the two-and-a-half years when we couldn’t fly anywhere, gathering all the stuff, photographing, sending [pictures] to us.

“We would tell her what we needed and what to dig out. Thankfully she also had a good grasp of the Library of Congress, a really unwieldy repository, which she was able to navigate.”

Other items were procured closer to home, but often not without difficulty.

And then there were the letters.

“We knew we needed a letter written by Pei in Chinese because everybody has this doubt: did he really write and speak Chinese?” says Surya. “We found the letter [to his parents, about enrolling at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology], but it was so hard to get from the Shanghai Municipal Archives it took almost a year and a half.”

Not that the detective work always paid off.

“We had two models we wanted to include from the German Historical Museum in Berlin,” says Surya, referring to a site model and a close-up model of the museum, to which Pei had added the Pei Building extension in 2003. “But we couldn’t get them because they have impossible terms of loan – it was impossible to cover full liability for them.”

The lamp Surya mentions, in cloisonné enamel and designed for the Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing, which opened in 1982, is pictured in the book of the retrospective, published by Thames & Hudson.

Also titled I.M. Pei: Life Is Architecture and edited by Surya and Chen, the abundantly illustrated monograph is so exhaustive in its essays about, and assessment of, Pei’s work, life and influence, with contributions from family, friends, colleagues, former government ministers and many others, that it amounts to an oblique biography.

But book and show also serve another function.

“Our intentions were clear: we didn’t just want to do a blockbuster exhibition and sell tickets,” says Chen. “We thought it was time to position Pei in the broader arc of scholarship.

“Related to the fact there was never an exhibition before is that he was not so involved with academia. A lot of the ‘starchitects’ who get museum shows, it’s all a package: they write theoretical texts, teach at one of the top architectural schools and develop research with their students. Then they get the exhibitions. It’s all part of the elevation of architects into ‘starchitects’.”

Pei was influenced by one proto-“starchitect” long before the term was invented. The philosophy and works of Le Corbusier exerted a long-lasting effect, as did the traditional architecture of mainland China, not least Suzhou’s garden villas, which first captivated Pei as a teenager.

Yet despite having much to impart, “Pei didn’t teach,” says Chen. “He wasn’t very active in the world of theory and that resulted in his being very understudied.

“There was remarkably little scholarship around him and it was important for us to help build that scholarship.”

On the retrospective’s opening day, Sandi will be among speakers at a free, public M+ talk about the legacy of his father – a man who, in 1976, while still approaching peak power, was famous enough to be depicted in a New York Times cartoon alongside Robert Redford, Stevie Wonder, Mikhail Baryshnikov and other luminaries.

“I guess he was a superstar when I was fairly young,” says Sandi. “By 1976 my father was quite a recognisable figure. I guess I was aware of that – because that’s how I got into graduate school! Please don’t tell anybody.”

“It was called ‘the year of Pei’,” says Sandi.

Sandi didn’t work on the Louvre Pyramid – decried by French newspaper Le Monde as “a house of the dead” – but he was closely involved with the design of the Bank of China Tower.

“He knew it was a sensitive issue in Hong Kong and something he couldn’t avoid having to address. But he did find in the bank a client that accepted his design and was eager to support it.

“That was the most important thing for him. And I think in time, much like the situation with the Louvre, the public came to embrace the building.”

The M+ initiative is a homecoming for Guangzhou native Pei, who lived in Hong Kong as a child, left Shanghai to study in Philadelphia in 1935 and became an American citizen in 1954.

“He really loved going to Hong Kong,” says Sandi. “He had many friends there and loved to go for the restaurants and the tailors. I would often carry his suits and shirts back to New York.

“I think he’d be impressed by the exhibition. It’s much more in-depth than he might have imagined. He probably would have thought it would be [just] about his buildings. But it is so much more.”

“I.M. Pei: Life Is Architecture”, M+, June 29 to January 5. Visit mplus.org.hk for more details.