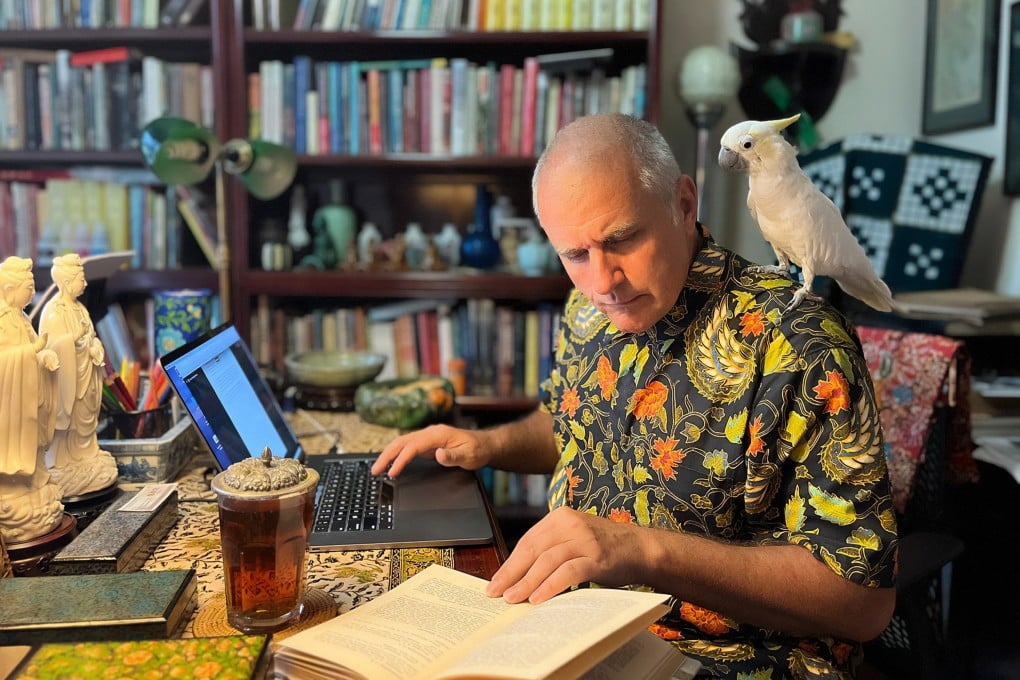

Then & Now | After 25 years writing for the South China Morning Post, Jason Wordie tackles the editorial elephant in the room

No, he isn’t told what to write about, says the long-standing SCMP columnist as he looks back on a quarter century documenting the region’s huge changes – from Macao to Macau, and Pearl River Delta to Greater Bay Area

Sorting out long-ago files a few months ago, I realised with a jolt that – give or take a few short breaks – I have been writing historically based columns in the South China Morning Post – mostly in Post Magazine – for 25 years. Being confronted with a few dozen scrapbooks filled with yellowed, brittle clippings offers a milestone of sorts in anyone’s life, and the thought of that anniversary gave me pause.

What have I written about, and how have my views on those subjects changed – or not – in a quarter of a century? Old age is now closer than youth, so looking back is perhaps inevitable. And within that expanse of time, personal viewpoints will inevitably modify; likewise, what one chooses to remember, or prefers to forget, also becomes clear. Tempus fugit and all that.

Being a regularly published writer presupposes regular readers; and those readers sometimes have some curious ideas of their own, as various comments posed over time make plain. The most frequent question – quite understandable in Hong Kong, even if completely mistaken – is: do “they” tell you what to write every week? As though some list of potential topics is drawn up by unseen others, carefully vetted for real or guessed-at sensitivities, and then diligently followed, with little or no personal autonomy in the matter. This has never, ever happened. Other than occasional suggestions that something or other would be an interesting topic – and it is usually readers who make these – Then & Now is, and always has been, an individual version of local history, culture and society related as this writer sees fit. No doubt cynics might mutter, “Ah, but he would say that, wouldn’t he!” in an echo of British “showgirl” Mandy Rice-Davies’ immortal, much-quoted disclaimer on other matters; but nevertheless, this is completely true.

Never having worked a single day in a newspaper or magazine office does pose challenges for an individually minded weekly columnist. Some modification to different preferred usages is inevitable when editorial style sands shift, and red pencils change hands. And so, Sek Kong – the spelling by which I have always known my own corner of the New Territories – becomes Shek Kong. Macao with a final O is the official English spelling for the ex-Portuguese settlement across the Pearl River; herein, Macau is usual. We alumni generally refer to our alma mater as Hong Kong U – or Hong Kong University – seldom as the University of Hong Kong. But never mind, these are only minor quibbles.

Hong Kong remains an abidingly interesting place, with much that one simply could not invent

But what really has changed over the years? Hong Kong history – in both popular and more academic formats – is no longer a niche subject; observations expressed in the late 1990s were mainstream by the early 2010s. In the past decade, Hong Kong has steadily become a very different place to what earlier direction of political, social and economic travel may once have suggested by way of eventual destination. Distinctions between urban Hong Kong and the New Territories remain, but annually diminish. Terminologies shift; the Pearl River Delta (or PRD), the usual shorthand for Hong Kong’s sprawling mainland hinterland a quarter of a century ago, has been ambitiously rebranded the Greater Bay Area. Borders between Hong Kong and the rest of the country – evermore fungible with the passage of time – are now carefully called boundaries; likewise, distinctions between “countries, territories and regions” must remain utterly unambiguous.