Review | Behold the history of men’s fashion and see how splendid it used to be

- ‘Fashioning Masculinities’, the catalogue from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s current exhibition, is full of beautiful images of menswear through the ages

- The publication reminds us that there once were alternatives to today’s sobering styles, gesturing towards a more colourful and extravagant future

It’s been more than a decade since social critics began to lament – or celebrate – the “death of men”.

The idea was that in a technologically advanced world where connection and cooperation were indispensable to success, masculine virtues – physical strength, bravery, stoicism – were no longer necessary while once tolerated masculine vices – violence, anger issues, recklessness, emotional detachment – were increasingly unacceptable.

Men, it turns out, have not quite died out yet. Some are clinging to the old ways in a desperate attempt to retain patriarchal privilege. But others are reinventing masculinity, drawing on the most evocative, seductive and charismatic examples from the past to fashion a new man who doesn’t so much defy conventional gender roles as transcend them.

Fashioning Masculinities, the catalogue from the current exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London, comes along right on cue to illustrate and explain 21st century masculinity.

The book contains short, savvy essays exploring aspects of masculine fashion. And it is beautiful: full of crisply rendered images of paintings, photojournalism and photographs of garments from the V&A’s unparalleled collection.

The sumptuous images illustrate the authors’ sometimes dense arguments and serve as easy-to-digest eye candy for those who might only thumb through the book.

Like the exhibition, the book is divided into three themes.

“Undressed” focuses on changing ideals of the masculine form, undergarments and nude representations. It includes essays discussing grooming rituals in the 18th century, the influence of classical sculpture in the early 19th century, the rise of bodybuilding in the late 19th century and homoerotic photography in the 20th.

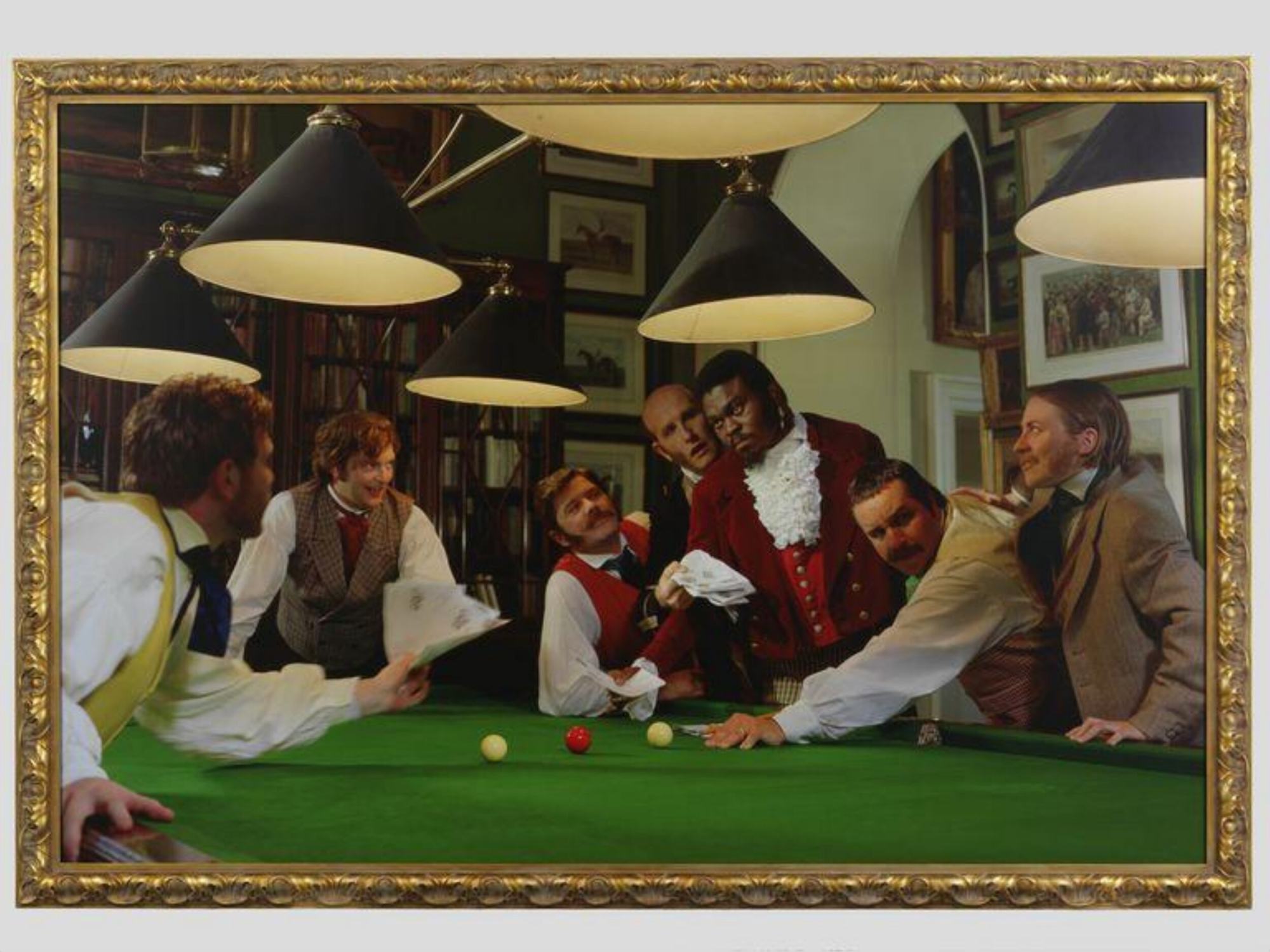

“Overdressed” looks at the flamboyant masculine fashions of earlier historical periods and explores why masculine fashions turned away from extravagance and splendour to adopt the sober and unassuming styles such as the dark-wool business suit.

British dress reformer and psychologist John Carl Flügel called this change the Great Masculine Renunciation and was the first to wonder what led 18th century Western men to give up the sumptuous, sexy fashion that their ancestors enjoyed (spoiler: the suit is actually a lot more sumptuous and a lot sexier than it might seem).

In this section of the book we see Tudor-era crimson doublets, Regency-era brocade and the streamlined but obsessive style of Beau Brummell alongside essays dealing with the history of “swagger”, the figure of the dandy and the influence of the kimono on European fashion.

“Redressed” looks at masculine fashions through a more present-day lens: when the essays refer to styles of the past, they do so to explain contemporary trends.

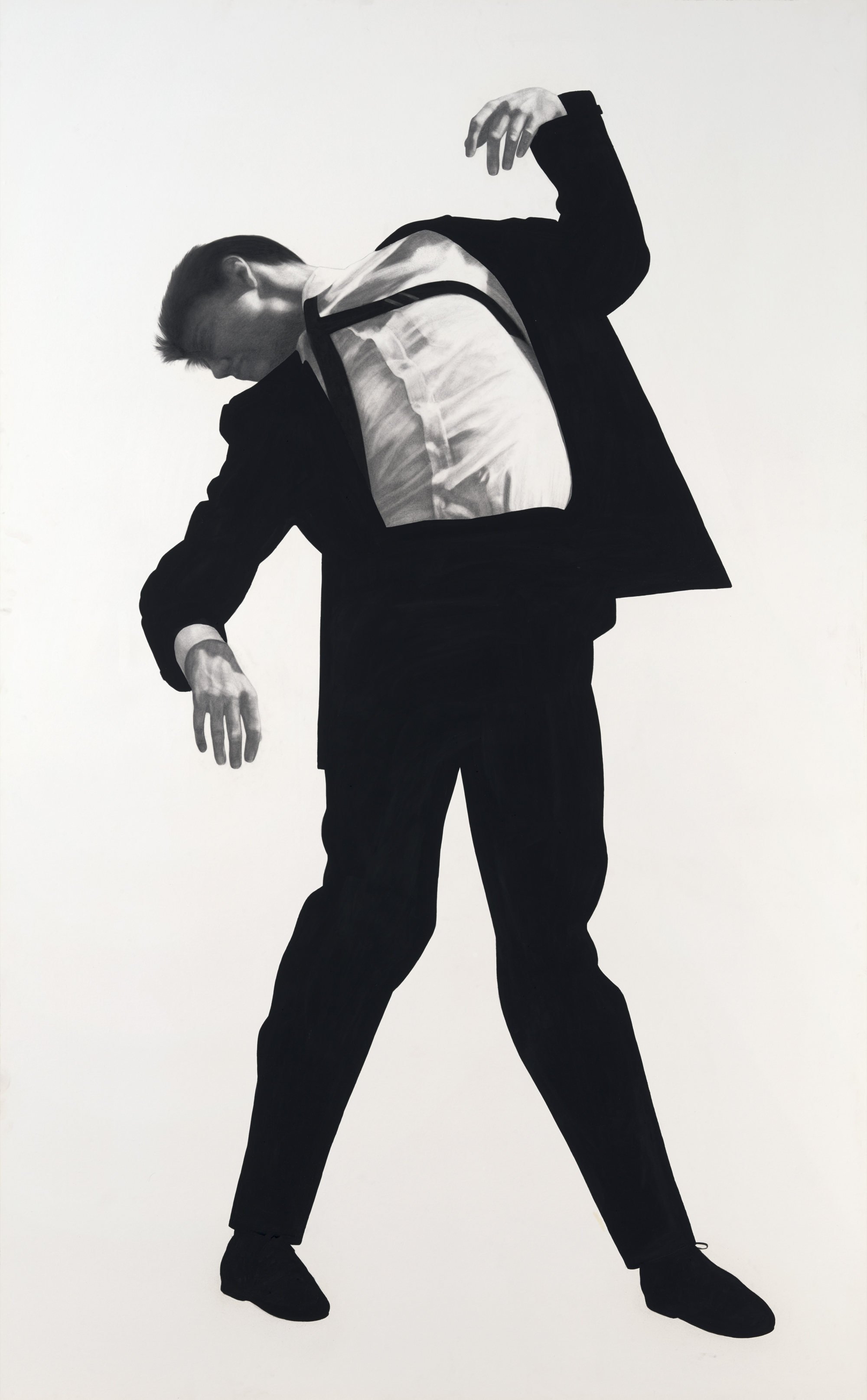

A stand-out essay, “Monochrome Man”, by Christopher Breward, looks at the long history of anything-but-basic black: it convincingly re-tailors the common idea that the black business suit represents the height of masculine self-abnegation, pointing out that black had long been a costly and lavish colour, with intimations of luxury, indulgence and perversity as well as those of sobriety and self-denial.

There’s an illuminating discussion of the evolution of men’s headwear and a revealing, if a tad too-earnest look at fashionable gender transgression.

Some might complain that Fashioning Masculinities is relentlessly Eurocentric. Race is given its due: for instance, a terrific essay looks at the “rude boy” styles of Black Britons in the 1970s and 80s. An essay on kimonos moves deftly between changing styles in Edo period Japan and the adoption (today, some would say “appropriation” but the author, thankfully, does not pass judgment) of the garment by men in the West.

But an essay near the end of the book addressing South Asian styles, while well crafted, seems almost tacked on to satisfy the diversity police. And a discussion of the utilitarian “Mao suit” focuses mainly on its adoption by Parisian radicals in the 60s and European designers in the 70s.

It’s a missed opportunity because that garment played an important role in anti-colonial politics: it was dubbed the abacost (short for à bas le costume or “down with the suit”) by President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, who wore it to symbolise an agenda to rid the country of European influences.

But perhaps Euro-centrism is part of the point. A work of the depth and detail of Fashioning Masculinities requires focus, and given the V&A’s location and its collection, it was natural that the exhibition and its catalogue would focus on Europe.

The history of African, Asian and pre-Columbian American fashion, while as rich as that of Europe, is distinctive and needs its own treatment. Maybe it’s more respectful not to attempt a superficial treatment of non-Western traditions simply for the sake of inclusiveness.

After all, European fashion developed a distinctive type of masculine style: there was nothing like the Great Masculine Renunciation in any other part of the world. Moreover, European fashion followed the flag and colonised much of the world as the West made its fashions global signs of modernity.

Like it or not, European fashion has been as influential in Hong Kong, Tokyo, Kinshasa and Mumbai as in Paris, Naples, New York or London.

Even as the Western style of cocky, imperial masculinity comes under attack, its aesthetic retains much of its seductive power. And until recently, most men outside the bohemian domains of the arts haven’t seen a viable alternative.

Fashioning Masculinities reminds us that there once were alternatives, gesturing towards a future that retains the appealing wardrobe of the modern man while leaving his more toxic baggage behind.

Richard Thompson Ford is a professor of law at Stanford University and author of Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History (2021), available in English and Japanese, and forthcoming in a Chinese translation.

Fashioning Masculinities: the Art of Menswear Edited by Claire Wilcox and Rosalind McKever, published by V&A Publishing