Review | The inherited trauma of the Killing Fields for Khmer Americans infuses the short stories Anthony Veasna So left behind before he died, and collected in Afterparties

- Drugs, teenage hookups, struggling family businesses and reincarnated relatives – Anthony Veasna So writes engagingly about a community of which he was part

- His stories are full of poignancy, with scenes that stay long in the mind; they are made all the more so by the knowledge there will be no more from his pen

Afterparties: Stories by Anthony Veasna So, pub. Ecco Press

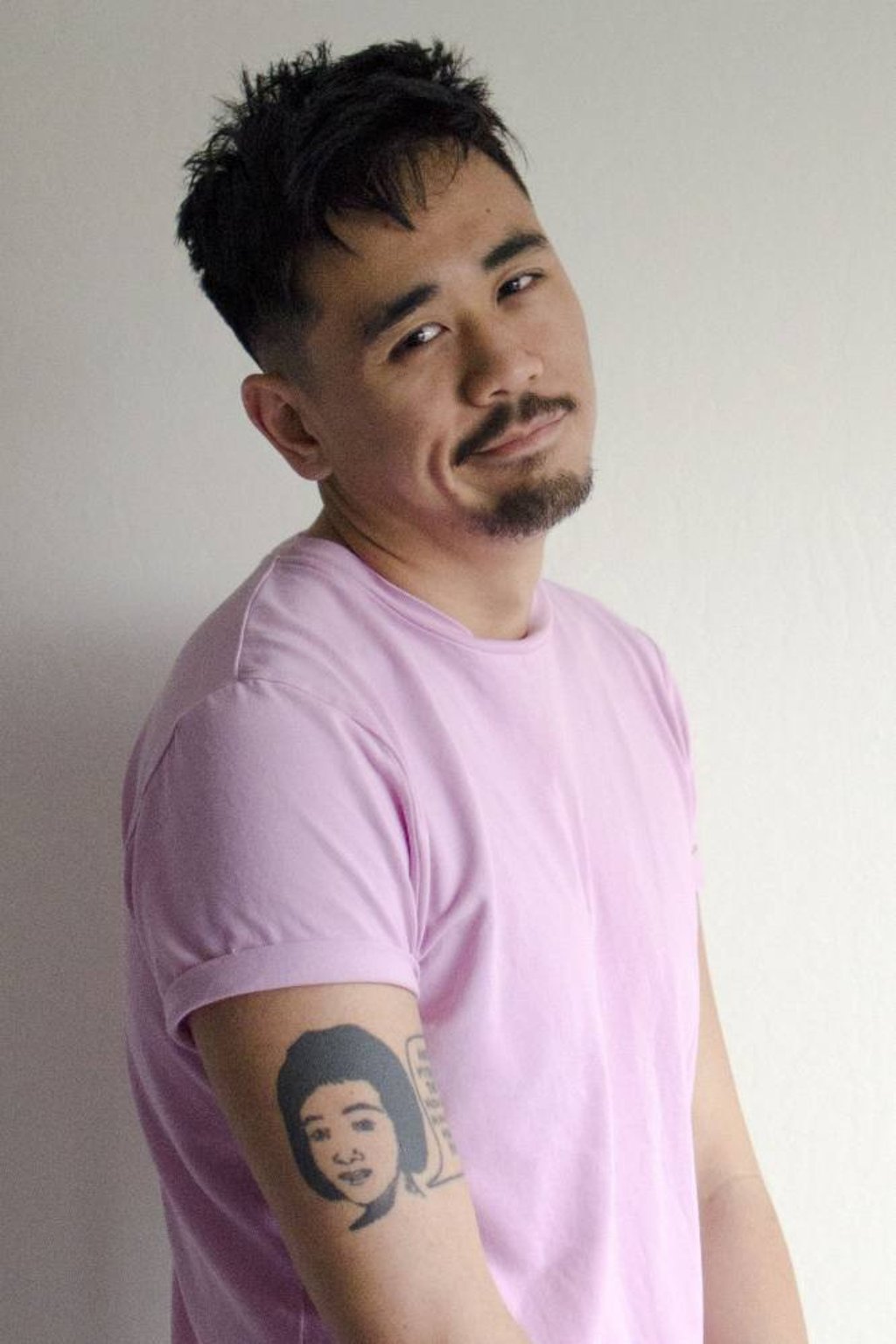

When Anthony Veasna So died in December, aged just 28, he left behind a reputation as an author on the brink of stardom, a powerful voice for other Khmer youth growing up in America in the shadow of the collective tragedy of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations.

Now, a collection of his short stories, Afterparties, has been published, helping his fiction to reach a larger audience. Many of the tales have already appeared in leading magazines, including The New Yorker and literary journal n+1, but Afterparties offers a chance to read them as a whole, and combined they feel far greater than the sum of their parts.

The nine stories are filled with vignettes of Cambodian-American life, with younger generations growing up burdened with the inherited trauma of life under the Khmer Rouge, the vicious regime that ruled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979 and instigated a genocide that killed up to two million people, a fifth of the country’s population.

The stories are melancholic in tone, but many are also filled with humour and touching moments of families trying to understand one another.

From the opening story, “Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts”, we have a glimpse of the many facets of the Khmer-American experience. In it, a mother and her two daughters run a struggling doughnut shop in California. The mother realises she’s slaving away as her own mother did “until she grew old and tired and the markets disappeared and her hands went from twisting dough to picking rice in order to serve the Communist ideals of a genocidal regime”. A strange nightly visitor offers the daughters something new to focus on, and gives them a chance to unlock what it now means to be Khmer.